Commentary on Mark 15:16-39

For those of us reading the Bible today, Jesus’ death on the cross is portrayed as a singular event. Indeed, for us, it is. For the Romans, it was probably just another Friday. For the disciples, it seemed like the end. For us, Jesus’ death on the cross becomes the pathway to eternal life.

Crucifixion in the ancient world

Crucifixion was an exceedingly shameful and painful death. It was a punishment typically reserved for non-Romans and the non-elite. The Roman practice of crucifixion was meant to serve as a deterrent from committing crimes. Quintilian, in his description of crucifixion, indicates that the victims were placed on “the most frequented roads … where the greatest number of people can look and be seized by this fear. For every punishment has less to do with the offense than with the example.”1

The vertical beams would be located outside the city gates, and the victims would carry the horizontal beam to be affixed to the vertical beam.2 Often, there would be an inscription of the crime above the victim to serve as an additional deterrent from their particular crime.

The Lex Puteolana, an inscription found in Pozzuoli, offers one of the most detailed descriptions of what crucifixion would entail, including the colors worn by those crucifying the victims. The Lex Cumae, likely a document paired with the Lex Puteolana, indicates that the cost for crucifying an enslaved person was eight sesterces, about the cost of a glass of wine. While these documents are far afield from Roman-occupied Judea, they give a sense of the ways some areas within the Roman Empire regulated crucifixions.

For the Roman soldiers, Jesus’ crucifixion was likely routine. Michael Bird indicates that crucifixions “were common in places like Judea,”3 though we do not often hear about how widespread they were. While we do not have indications of other messiah, prophet, or king claimants being crucified, there are reports that the Romans beheaded or imprisoned others with such claims.4

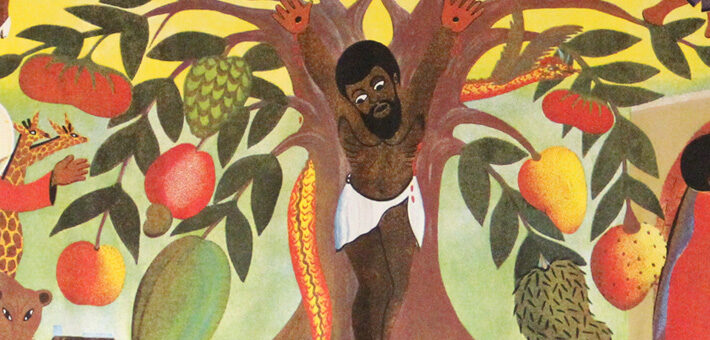

Jesus’ crucifixion

Given the likelihood that crucifixions were commonplace in Judea, one could easily imagine that the vertical cross beams were already located outside the city. “Crucifixion was the Roman way of saying, ‘If you mess with us, there is no limit on the violence we will inflict upon you.’”5 Crucifixion demonstrated Roman power and the capacity for rendering those who threatened its power as less-than-human, literally dehumanizing them. What this narrative of power fails to account for is that one cannot dehumanize another without losing their own humanity.

Jesus is not crucified alone. We do not know the stories of the other two men. We do not have reports of them being flogged and taunted, which would have been standard treatment for crucifixion victims. There is no indication of them carrying their crosses and proceeding with Jesus, though it would make sense if they had, making a testament to all the pilgrim onlookers who flooded the city for Passover.

The charge against the two men (lēstai) is often used to describe insurrectionists or freedom-fighters, which makes sense in terms of why they were being crucified. Roman power—and how Romans responded to threats to that power—was on full display this Passover. The people who gathered to celebrate God’s liberation and deliverance of the Hebrew people had a physical reminder that they were not, in fact, free: they were beholden to Rome.

It would let us off too easily, however, to place blame on Roman power narratives or on any other party whom we might determine has responsibility for Jesus’ death, for that matter. Jesus’ crucifixion reflects back to us the human capacity for violence and, at the same time, stops this tendency in its tracks. The devastating irony and sarcasm of those who taunt Jesus make for a chilling narrative of humans’ own capacity to dehumanize others. The soldiers dress Jesus in purple and give him a crown of thorns, hail him king, and kneel down in mock homage, spitting on him. The crowds use Jesus’ own words to taunt him, insisting he save himself. But Jesus did not come to save himself.

Even those crucified with Jesus taunted him. And we respond, “Someone should have done something.”

Jesus reflects this narrative back to us as we encounter human suffering. “God used our sin to save us from that sin. God did this so that victims of such acts would never be invisible—they look too much like Jesus.”6 Jesus’ solidarity with victims of violence, oppression, and tyrannical regimes reflects back our own complicity in these systems. James Cone asserts that this solidarity is the scandal of the Gospel:

The real scandal of the gospel is this: humanity’s salvation is revealed in the cross of the condemned criminal Jesus, and humanity’s salvation is available only through our solidarity with the crucified people in our midst.7

Jesus draws us into community with those who suffer because he is in solidarity with those who suffer.

In the end, Jesus’ cry of “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” (Psalm 22:1) suggests utter abandonment. It is at this point that someone finally shows Jesus mercy by offering him wine mixed with myrrh, likely intended to help alleviate his pain.8 Jesus dies, the cry still echoing in the air.

The questions of theodicy hang with us today: Where is God when the innocent suffer? Why does evil persist? Just as Jesus has taken on the sins of humanity in solidarity with those who suffer, in this cry Jesus takes on our theodicy. Where is God when the innocent suffer? God is on the cross. What does God do in the face of evil? God stands with us, protesting against it. Where is God? With the temple curtain torn in two, God is out loose in the world.9

Notes

- Quintilian, Declamations 274, ed. and tr. R. Shackleton Bailey (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006).

- In some crucifixion practices, there was only a vertical beam, though it was more common in the first century to also include the patibulum, or horizontal beam.

- Michael Bird, “The Horror of Crucifixion,” Word from the Bird, March 9, 2022, https://michaelfbird.substack.com/p/the-horror-of-crucifixion.

- Some were near-contemporaneous with Jesus: Simon and Theudas put diadems on their heads, signifying kingship, and were beheaded (Josephus, Ant. 17.10.6; 20.5.1); Anthrogenes claimed to be a prophet and was imprisoned (Josephus, Ant. 17.10.7). The first two events occurred not long after the death of Herod the Great (ca. 6–4 BCE), and the last event occurred in the year 46 CE, according to Josephus.

- Bird, “The Horror of Crucifixion.”

- S. Mark Heim, “Saved by What Shouldn’t Happen: The Anti-Sacrificial Meaning of the Cross,” in Cross Examinations: Readings on the Meaning of the Cross Today, ed. Marit Trelstadt (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2006), 224.

- James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2011), 160.

- Some have suggested that this offer was an additional insult, which would fit with the taunting narrative, but the first-century audience would have likely understood it as a pain-killing compound.Brett Leslie Freese, “Medicinal Myrrh,” Archaeology 49, no. 3 (May/June 1996), accessed February 16, 2024, https://archive.archaeology.org/9605/newsbriefs/myrrh.html.

- Donald Juel, Master of Surprise (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994), 35–36.

- PRAYER OF THE DAY

Son of God, your suffering for our sin is great. We offer you all that we have and all that we are. Restore us as we are reminded that we are redeemed because of all you have done. Amen.

HYMNS

Were you there ELW 353, GG 228, H82 172, NCH 229, UMH 288, TFF 81

Jesus, remember me ELW 616, GG 227, UMH 488

CHORAL

Crucifixus, Antonio Lotti

March 29, 2024