Commentary on Matthew 18:15-20

Churches are full of troublesome people.

We are rather expert at spotting those rabble rousers around us, identifying their destructive habits, and condemning the ways they seek to destabilize our communities. Noticing when we are engaged in these very same behaviors is another story. After all, some of those troublesome people are us.

Two weeks ago, we noted how rarely the Gospel writers refer to the “church” by explicitly using the term ekklesia. Two weeks ago, Jesus commended Peter’s faith and declared that the “church” will be built upon that critical moment of faith. In our passage, the church is once again mentioned, not to establish its foundation so much as to note the ways in which that foundation is so easily destabilized by conflict.

After all, the “church” was not born until the resurrection inaugurated its mission in the world. The “church” (that is, that body of believers bound by faith in the crucified and resurrected Christ) was a future reality for Matthew’s Jesus. In a sense, he speaks wisdom to a community not yet founded. In these two references to the “church,” we may see most clearly the kinds of concerns that drove the composition of Matthew’s Gospel. These two narratives may describe the deepest concerns of Matthew’s community, concerns so important that Jesus himself addresses them directly.

But this is not the only connection between these two passages. In both, Jesus reminds the faithful of the great power they wield as a gift from God (see 16:19 and 18:18). The Spiderman mythology gets it exactly right: with great power comes great responsibility.

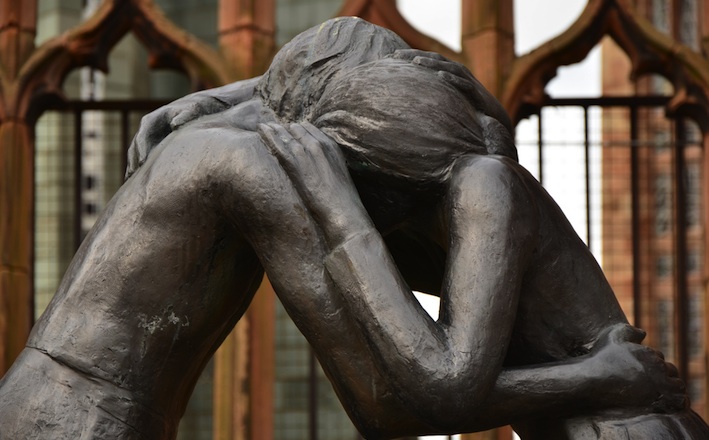

At the confluence of community and power, Jesus is instructing his disciples. Community is vital and God’s gift to us and the very setting in which God will move among us. And yet that community, as we know too well, has to be preserved, protected from bitter rancor and pointless dissension.

The guidelines for communal discernment and confrontation tap into the community’s own resources of witness. Unresolved conflict ought not to happen in a silent corner, behind closed doors where differences in power can overwhelm the weak. Neither should they happen through whispered rumors where the corrosive effect of gossip can pervade our lives.

Instead, you begin with a direct addressing of the issue and then a witness to your case, someone who presumably sees things the same way you do. That failing, you move through larger circles of involvement in the community, eventually granting the community the duty to expel the offender, to treat him or her like a “tax collector or Gentile,” that is, as an abject outsider to the circle of the faithful.

These are not decisions to be taken lightly, for the decision of the community at that point resonates in the heavens. Remember the context in which Jesus first tells Peter about the power of binding and loosening. In that earlier verse (16:19), there is a synchronicity between heaven and earth, between our actions and God’s actions. So too here. Expelling this individual is not just a matter of communal cohesion but a matter of life and death. With great power comes great responsibility.

Matthew’s Jesus concludes with the power of numbers. When two siblings in the faith concur so does God. Wherever two or three gather, there God dwells. That is, these communities are sacred ground, which is precisely why conflict needs to be addressed and precisely why divisive sisters or brothers cannot be allowed to tear God’s people apart. How we relate to one another in Christian community is a concern in God’s heart.

So, is this a good blueprint for church conflict today? Must we confront one another with these prescribed steps and swerve from them only to our detriment? Do we in a culture with so many choices in churches really dwell on the power we have to exclude some from our midst? After all, don’t people leave churches all the time for any number of reasons and find another place to call a spiritual home? Don’t churches split for any number of reasons? In a culture that does not seek out belonging in churches, do we still heed this call to community, to mutual belonging?

To be clear, this is no mere handbook for resolving conflicts. Simply following this order of confrontation will not ensure a result consonant with God’s hopes. It is not as simple as moving through these steps. We know that the mechanics of decision-making do not always reflect our values. Checking off these duties step-by-step will not guarantee a decision rooted in God’s love for us. This process could so easily be co-opted by selfishness and dislike and so many human frailties. Instead, what matters here is the concern for the other and the community imbedded in these steps.

We ought to remember that what makes a church a church is precisely the presence of so many troublesome people. That the expulsion of the troublemaker is a last resort, a human condemnation that so easily redounds with divine implications. That Matthew’s Jesus must assume that most conflicts will be confronted well with step one or step two, never requiring the harsh step of estrangement.

In short, the steps Jesus lays out here are not a mere blueprint so much as a statement of communal values and an acknowledgment of both the frailty as well as the utter necessity of communal discernment. Love requires that we address the inevitable conflicts that will arise among us. It is not enough to sweep them under the rug and thus allow them to fester. Unaddressed conflicts can render a community unable to function as God hopes. But neither is rejection our first instinct. Separation is not to be taken lightly even when it proves necessary.

As we preach a text so full of certainty about community and who belongs in it, we might wonder where forgiveness, doubt, and humility are to be found. Must every unresolved conflict result in separation? Will our inevitable conflicts lead to inevitable separation? To that we will turn next week.

September 7, 2014