Commentary on John 18:1—19:42

Who has power? In the world, there are many claims to power and illusions of power.

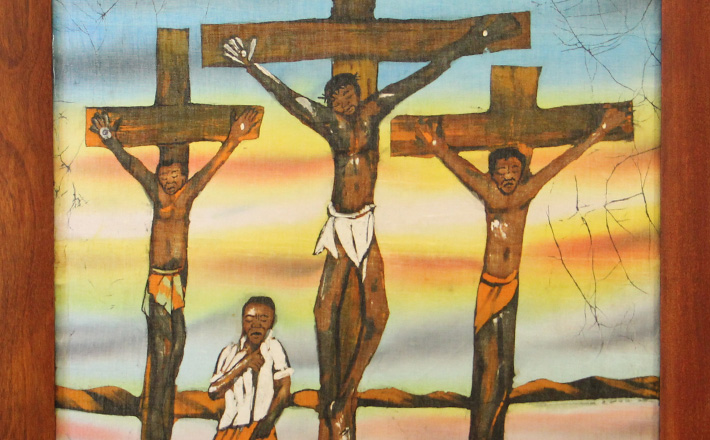

John crafts the passion narrative so that the reader may come to see the power of God in a man executed as a criminal by the Roman state.

Jesus’ power is portrayed in part through his control over the events of his death. He exhibits divine knowledge and control over all the events of his passion. In Jesus’ arrest, his divine power is fully visible. Identifying himself as the one the soldiers seek, Jesus declares “I am” (18:5, 6, 8; ego eimi, NRSV “I am he”), a shortened version of the name of God “I am who I am” (cf. Exodus 4:14). The soldiers step back and fall to the ground, an appropriate response to a revelation of the divine, but one that is wholly inappropriate in the context of the arrest scene. Jesus’ divine power is clearly manifest, yet he does not intervene to alter the course of events.

We see Jesus’ acceptance of and control over events in comparing John with the Synoptic Gospels. The Synoptic Gospels all record Jesus’ request that this cup pass from him (Mark 14:36; Matt 26:39; Luke 22:42). Yet John’s Jesus poses a question: “Shall I not drink the cup that the Father has given me?” (18:11). The answer is meant to be obvious. Jesus intends to fulfill the task for which he has been sent. Jesus also carries his cross by himself (19:17), a contrast to the Synoptics, where Simon of Cyrene carries the cross (Matt 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26).

Most scholars agree that John did not know or use the other Gospels in composing his own, and the point is not to assert that one Gospel is right or wrong, or to speculate about the composition history of the Gospels. Instead, these details set in relief the way John crafts his story to shape the character of Jesus. He is fully in control, even in these events of his execution.

Jesus’ interactions in the trial narrative also underscore his power. He responds to questions from powerful people by asking them questions in turn: “Why do you ask me?” and “Do you ask this on your own?” (18:20-21, 34). Similarly, Jesus declares that Pilate would have no power over him unless it were given from above (19:10). The conversation calls into question the knowledge and power of the worldly authorities Jesus confronts.

One final detail peculiar to John underscores Jesus’ ultimate control over the events of his death. The Greek paradidomi (to betray or hand over) appears frequently in this narrative. It describes Judas’s betrayal of Jesus (18:2, 5). Jesus is then handed over to Pilate (18:35). Pilate hands Jesus over to be crucified (19:16). But in the end, Jesus “hands over” his spirit (19:30). Jesus’ control is not meant to lessen the responsibilities of each party to his death, but reminds the reader that Jesus is not simply an unwitting victim of an unjust trial. He seeks to “drink the cup that the Father has given” him.

Throughout the narrative, John encourages the reader to think through the significance of Jesus’ death using the metaphor of kingship. From the beginning the trial before Pilate centers on the question, “Are you the King of the Jews?” (18:33). Pilate and the Jewish leaders engage in an elaborate political exchange, in which Pilate taunts the Jews with the image of Jesus their captured “king,” and the Jews take up Pilate’s claim as a tactic by which to have Jesus killed for “setting himself against the emperor” (cf. 19:12).

Two important things emerge from John’s use of the metaphor of Jesus as king. The first is that Jesus’ crucifixion corresponds to his enthronement as king. Pilate inscribes a title above the cross, “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” (John 19:19). A similar inscription is found in all four Gospels (cf. Matt 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38), but John expands the narrative at this point. The inscription is written in three languages and posted where many see it.

In this sense, it shares the form of other declaration by the ruling powers. When the chief priests protest, Pilate’s response adds a tone of formal proclamation: “What I have written, I have written” (John 19:22). Through John’s description, the reader sees the reality of Jesus’ kingship even in the moment of his crucifixion, and even as others deny it.

The second important element of Jesus’ kingship is intertwined with the Passover metaphor. As Jesus’ “hour” approaches, the narrator repeatedly reminds the reader that the Passover festival approaches as well. In the Synoptics, the day of preparation for the Passover (the day on which the Passover meal is prepared and eaten) is on Thursday. Jesus last meal with his disciples is a Passover meal (see Matthew 26:17-30; Mark 14:12-25; Luke 22:7-23).

John’s chronology is different. He aligns the moment of Jesus’ condemnation with the arrival of Passover. At the climax of Jesus’ trial, John writes, “Now it was the day of Preparation for the Passover; and it was about noon.” (19:14). A slightly later source indicates that noon was the time that the Passover offerings began to be slaughtered in the temple in preparation for the Passover meal. John carefully brings Jesus’ death in line with that of the Passover offering.

The climax of the Jews’ argument with Pilate over Jesus’ kingship also occurs at this moment. Pilate presents Jesus as their king (19:14), but the people cry out for his condemnation. “Pilate asked them, ‘Shall I crucify your King?’ The chief priests answered, ‘We have no king but the emperor.’” (19:15). Passover is, in part, a time of remembrance of God’s kingship. God vanquished the Pharaoh of Egypt in a show of power. At the moment the Passover begins, John has the Jewish leaders speaking blasphemy. Instead of proclaiming their allegiance to God, they declare: “We have no king but Caesar.”

John’s irony runs deep here, but it is not meant as a wholesale criticism of Judaism, and Christian interpreters should take care to avoid the all-too-common slander and stereotypes of “the Jews” on Good Friday. John agrees with the central tenets of Judaism that God is king, and that to say otherwise runs against Jewish law. He crafts the story in such a way that the reader may see how the Jewish leaders’ rejection of Jesus’ kingship amounts to a rejection of God.

March 29, 2013