Commentary on Mark 9:2-9

Probably the greatest challenge about preaching on Transfiguration Sunday is dealing with the pressure to explain what the Transfiguration means.

Somehow we expect that we have to guide people toward making sense of why the Transfiguration occurred, or how the story functions within the plots of the Synoptic Gospels, or why the Synoptic evangelists thought they should include it, or what shaped the early Christian traditions about the Transfiguration, or what symbolic value should be assigned to the setting and Jesus’ two conversation partners, or what the event communicates about Jesus’ nature, or whether we should praise or criticize Peter’s comments, or why some people call it “Transfiguration Sunday” while others prefer the more melodious “Quinquagesima.”

Seriously? When has the idea of a brilliantly glowing holy figure ever “made sense,” anyway?

The transfigured Jesus isn’t supposed to be figured out. He’s supposed to be appreciated. We should be drawn to him, as if we were moths. On this day, help your congregation bask in the warm wonder of his glow. Here are three angles into the text that might serve your efforts.

A Jesus who will be seen

Epiphany began a few weeks ago with a story about a manifestation of Jesus’ identity, but it was a much more covert incident: Jesus’ baptism. In Mark’s account of the baptism, it’s not clear that anyone else sees the heavens slashed apart or the Holy Spirit diving into Jesus. The voice from heaven is Jesus’ alone to hear. Nothing’s public. Nothing’s obvious. Similarly, most of the epiphanies we get to experience in life consist of glimpses, and sometimes we aren’t even sure that they are really ours to see.

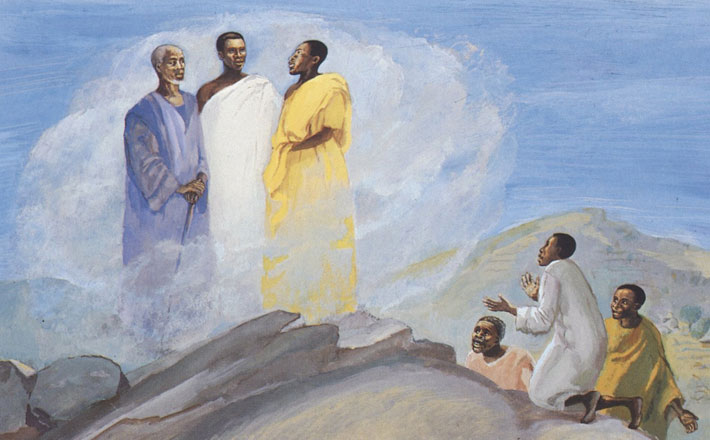

The Transfiguration is a very different kind of a revealing, however. Jesus becomes a beacon, like a lighthouse planted in the middle of the desert. The heavenly voice addresses all the witnesses: Peter, James, and John. On this Sunday, there is a promise that Jesus can and will be noticed. Epiphanies aren’t always subtle.

There is something almost — if you’ll promise not to giggle at the word — exhibitionistic about the Transfiguration. As a transfigured body clothed in shining garments, “Jesus insists upon being seen,” says novelist Mary Gordon, which means the Transfiguration narrative “can be read as the celebration of the visible.”1

In Mark’s Gospel, a story so full of concealment and secrecy, the Transfiguration says that this Jesus has plans to be conspicuous. What he will disclose is not necessarily the secrets of the universe or the meaning of life; rather, it’s himself. He may be hard to see clearly in all his intricate detail, what with the radiant glare and the transfigured body and all, but — sometimes, at least — he’s surely there.

Epiphany is for lovers

Because the Transfiguration is so bizarre and unusual, it can be easy to assume that we’re supposed to approach it with sober reverence and awe. But that isn’t how God views it. For God, the Transfiguration presents an opportunity to declare love for the one called “Son.”

If God is capable of smiling, this would be the occasion in which that happens. I don’t see how anyone can talk of one’s “beloved” without breaking into a pleased grin. That’s how lovers talk to and abut each other.

To return to Mary Gordon’s meditations on this story, she cites a translation of Matthew 17:5 that has God saying, “This is my beloved son in whom I take delight.” At the Transfiguration, then, “we are in the presence of delight. Delight as an aspect of the holy.”2 A sermon on Mark 9 can elevate this sense of delight. The Transfiguration does not sketch an image of intimidating purity or self-satisfied and inviolable majesty. It’s tender holiness. The scene is a reminder that holiness, as a characteristic of God, is participatory and shared. God loves, so God interacts. This holiness expresses itself in self-giving, for that’s what happens when someone adores and celebrates someone else.

Take delight in Jesus, for God does. As God expresses this delight, we gain a little more insight into the divine heart.

The promise of intimacy with God

The sights and sounds of the Transfiguration also suggest that Peter, James, and John find themselves on holy ground, in privileged company. After all, Jesus appears alongside Moses and Elijah, the two greatest prophets in Jewish memories.

Many things made those two ancient prophets great. For one thing, in the Bible each shares a moment of striking intimacy with God, through Moses’ face-to-face chats with God and his glimpse of God’s backside (Exodus 33:7-23) and Elijah’s encounter with God in a strange “sound of sheer silence” (1 Kings 19:11-13). When one is so close to God, everything changes. Impossibilities dissolve. After all, some Jews believed that both of these prophets successfully avoided death and were assumed directly into heaven, as recorded about Elijah in scripture (2 Kings 2:1-12) and as the first-century Jewish author Josephus reports about Moses (Ant. 4.323-26).

We should also note that both prophets, like Jesus, labored to help the people of God remain faithful as they were enticed by idolatrous religious ideas. All of them sought to keep the people of God hopeful as they suffered the burdens of abusive political systems. That is, Moses’ and Elijah’s closeness to God wasn’t something to be hoarded; it energized them in their service to others, equipping them to know and pursue the Lord.3

At the Transfiguration, then, Jesus stands in impressive company, sharing the moment with two others who know what it is to share close communion with God and to frustrate that pesky and seemingly unyielding boundary between life and death.

The bright light of the Transfiguration affirms life, a light that shines ahead into Lent to keep that season in perspective, never without hope and confidence. This light speaks a promise that God is here. And that God is knowable. God seeks relationship. Because God is life.

Notes:

1 Mary Gordon, Reading Jesus: A Writer’s Encounter with the Gospels (New York: Pantheon, 2009), 42.

2 Gordon, Reading Jesus, 42.

3 Scripture also anticipates roles for Moses and Elijah that extend beyond their (first) lives: Deut 18:16-20 and Mal 4:4-6.

February 15, 2015