Commentary on Psalm 50:1-6

What will it take for us to see — really see?

What will it take for us to see Jesus for whom he really is? What will it take for us to see God? And perhaps hardest of all, what will it take for us to see ourselves?

The combination of Psalms 50 and 51 in the propers for Transfiguration and Ash Wednesday might help, and the preacher might want to make use of this connection in sequential sermons. Psalms 50 and 51 are deeply connected — much more so than in their consecutive numbering. They are mirror images of one another, each one amplifying the other.1

Among many other connections, the two psalms together form a concentric pattern:

A 50:1-6 On Zion and sacrifice (today’s text)

B 50:7-15 On sacrifice and deliverance

C 50:16-21 The rebuke

D 50:22-23 Call to repentance/divine wrath

E Ps 51 superscript The Nathan oracle

D’ 51:1-2 Turn to God/divine grace

C’ 51:3-9 Concession

B’ 51:10-17 On deliverance and sacrifice

A’ 51:18-19 On Zion and sacrifice

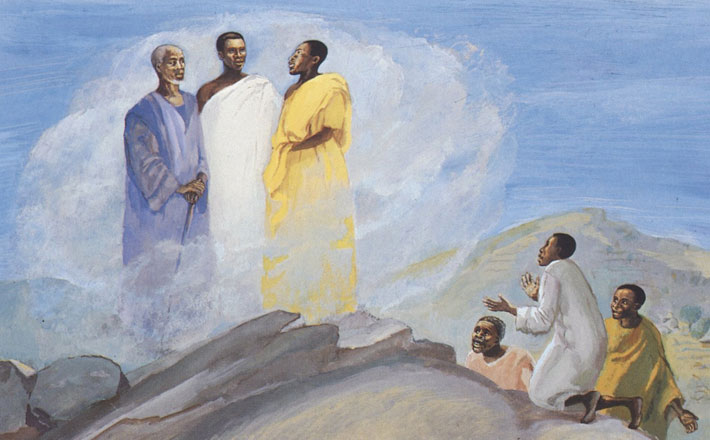

What will this mean for a sermon for the Festival of the Transfiguration? As is so often the case, a sermon on a psalm for the day must look more broadly than the liturgical use of the psalm as response. Response is one thing; proclamation is another. Responding to the story of the “translation” of Elijah and anticipating the Gospel account of the Transfiguration of Jesus, the opening verses of Psalm 50 are used to see (or at least hear) God in all God’s glory, summoning the entire earth along with the heavens to Mount Zion in order to see, hear, and proclaim God in the midst of fire and tempest. A big deal! A big God! This is the glorious God who will lead Peter, James, and John, following Jesus, up on another mountain to see a similar vision: the full glory of God reflected in the dazzling white robes of Jesus.

This could be enough. Suddenly, in a moment, the disciples see Jesus for who he really is, the one in whom the whole glory of God is revealed. This could be enough, but it would be a sermon on the Gospel rather than a sermon on the psalm. The psalm adds a clinker — one produced by that divine fire — that will throw things in a different direction. Yes, come and hear this amazing God, but you won’t like what God has to say: “Hear, O Israel, and I will speak, O Israel, I will testify against you. I am God, your God” (Psalm 50:7). True, we have to add another verse to the text to get to this unlovely line, but it is clearly where the psalm is going, and it is already anticipated in the description of God as “judge” in v. 6.

Is this why Moses and Elijah appear on the mountain? To signify the law and the prophets that have prepared the way for Jesus? Perhaps. But beware of tuning this into an Old Testament wrath/New Testament grace message. That movement happens already in the juxtaposition of Psalms 50 and 51. When God shows up, both judgment and mercy are present. The same thing is true when Jesus shows up. Jesus is savior, of course; but Jesus is also prophet, warning Israel of the very real consequences of sin. If all God’s glory is present in Jesus, that glorious fire will burn as well as enlighten.

The fire burns brightly in Psalm 50. The sacrificial system, meant to seal the promise of the covenant (v. 5) has been turned into a deadly “let’s make a deal” arrangement through which the people think they can buy God’s favor with the flesh of bulls and the blood of goats (vv. 12-13). Guess what! God doesn’t need us to provide for God. The sheep, cattle, and all that moves (including us) already belong to God. No deals!

We don’t do animal sacrifice, of course, but we do “offer” divine worship, and we can get that wrong, too — any kind of false worship and false assurances that “deal” way too lightly with the majesty and mercy, but also the justice and righteousness, of God. Then, the RSV translation of v. 9 takes on a new metaphorical meaning: “I will accept no bull from your house!”

The Transfiguration of Our Lord is a major event in the life story of Jesus, in the divine narrative of salvation. We do not want to diminish that. But this time around, we might want to probe more deeply (with the larger context of Psalm 50) the full import of coming into God’s presence, of hearing God’s word in its fullness. God is God, and we are not, so this is dangerous territory. The disciples were right to be terrified. It will take some figuring out to realize that this blazing fire burns only to purity, to make our robes as white as those of Jesus, to free us from our little attempts to tame God. To get out of the judgment with which Psalm 50 ends, we will need the contrition and forgiveness of Psalm 51. So, tell people to come back on Ash Wednesday.

Notes:

1 For my development of this argument, see Frederick J. Gaiser, “The David of Psalm 51: Reading Psalm 51 in Light of Psalm 50,” Word & World 23/4 (2003) 382394; online at https://wordandworld.luthersem.edu/issues.aspx?article_id=328 (accessed November 20, 2014).

February 15, 2015