Commentary on Micah 5:2-5a

Continuing the themes of Advent, Micah’s prophecy of deliverance comes with an adult dose of lament.

The lectionary leaves out the first verse which is helpful for understanding the current state of hopelessness in Jerusalem, “Now cut yourself, daughters of cutters, a siege is upon us; with a rod they strike the ruler of Israel upon the cheek.”1 Before Micah’s description of the coming king, it is appropriate to hear the distress. Tradition suggests that this fragment describes the moment when the Babylonians begin their siege on Jerusalem.The daughters of Zion are in danger of becoming the daughters of the marauding army. The leader of Jerusalem has been humiliated in his role, or perhaps incapacitated. Walled in the city as the Babylonian armies spread across the valleys beneath Jerusalem, hope begins to crack.

Hope is the partner of possibility. A siege is designed to close down possibility. With each passing day the option of survival slowly drains away. The sieging army doesn’t need to do much beside make sure supply lines continue to feed and secure the army. In a temperate climate with no second enemy, this logistical challenge is relatively easy: just set up camp and wait. As the sieging army waits, the hopes of those inside the walls begin to fracture. First the small fissures in the hope as they see the camps set up outside the walls. Then the cracks grow into a spiderweb as the storehouses grow empty. Hope is broken when finally, the sieged can conceive of only two options: death or surrender.

Social theorist Pierre Bourdieu conceives of human action as the complex negotiation of an imagination that is always calculating the possibilities for success. Only in folk tales and fairy tales do we conceive of social worlds where every possibility is equally available to every person. The truth is we do not all have equal access to the possibility of becoming a supreme court justice, or a professional basketball player, or a minister.

Bourdieu argues that all of us internalize the outside possibilities and let those internalized possibilities guide our imaginations. Every action is thus preceded by an unexamined subconscious calculation that asks, “Is that possible for someone like me?” Possibility is therefore also a question of power. “What power do I have to achieve my interests and is it enough?”

When our answers to the above questions are a solid “No,” hope wanes. But as Micah makes clear, while hope is easy to wound it is hard to kill. Though sieging armies want to limit the possibilities to two possibilities, the prophet refuses to be held captive by only two choices. The prophetic imagination has so much more to offer than just two options. Though the judge of Israel has been beaten down, another leader has been promised by God.

The prophecy admits that the sieging army will complete its task and Israel will be “given up,” but the story of God is not finished when the siege is completed. From a little town of Bethlehem will come another ruler, one in the vein of David — from Bethlehem but fit to rule Jerusalem. Micah continues to describe a time of security and peace where the leader, like David, will assume the role of shepherd of Israel. A leader who can feed his sheep. Contrast this vision, of course, with the humiliated leader in verse one who is unable to make peace as the sieging army starves the city.

If part of human experience is calculating how much power we have to achieve our interests, it is natural to also quantify what allies we can make to grow our power. The temptation then is to increase our possibilities in the world by borrowing the power of an ally. Since we cannot survive the siege, we join the siege. Since we cannot beat them, we become them. Power borrowed is better than no power at all.

The problem of course, is that our borrowed power never buys us true freedom. It only makes us a vassal to someone else’s interests. Yet, for Micah, the coming ruler is not borrowing earthly power, but is the arm of God’s power on earth. The coming ruler is God’s fullest expression of what God can do on the earth. Though the kings of Israel failed to protect the people, the coming ruler will secure the people of Israel. Though the dwelling place of Israel has been put under siege, this ruler will secure the dwelling for all time.

One of the marks of the prophetic imagination is its resilience. It refuses to be trampled. To be a prophet is to take the external possibilities and resist allowing their internalization. The outside possibilities ought never hinder our imagination of what remains possible.

Later, Christ will assure his followers, “with God all things are possible.” Within advent, a passage like this is a call back to the type of imagination that refuses to be bound by the historical moment. Values of grace, care, sensitivity and compassion seem in short supply. Advent is a time to assure the church that the wait will be honored. The promise will come true even when we don’t have the foggiest idea how.

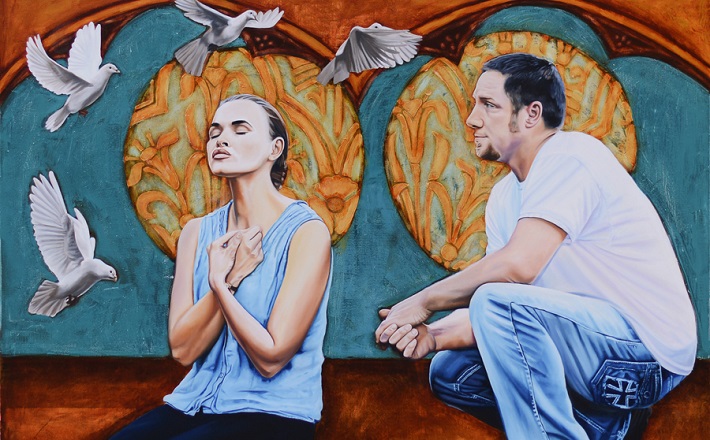

In the meantime, as the sieged wait, they daydream about the end beyond the end. That daydreaming is no silly trifle, but a way to preserve the hope that is fracturing. It is a way to expand the story beyond the immediate so that possibility might again join hands with hope.

Notes:

- This line is a strange one. The clause has sprouted a number of ingenious translations. I have provided my own to get the basic idea across. Not very poetic, I concede, but clear.

December 23, 2018