Commentary on Hebrews 10:5-10

The person of Jesus Christ — his will and voice and body — take center stage in this intriguing instance of New Testament salvific proclamation in the words of Israel’s Scriptures.

One more time now

The sermon labeled as being “To the Hebrews” is often charged with repetitiveness. At the beginning Hebrews 10 comes the assertion that the sacrifices of the law are ineffectual (10:1-4), a statement made several times already beginning in Hebrews 7 (7:19; 8:5-6; 9:9, 13-14). In this iteration of the problem, Jesus himself is brought forth to speak.

The last time Jesus had a speaking role in this drama of God’s redemption, he spoke of his stance of trust toward God on the one hand and proclamation to as well as possession of humanity on the other (Hebrews 2:12-13). While an argument can be made for the Son’s pre-incarnational presence with the Father and therefore a sharing in the other speeches of God, Hebrews 10 is the next time that the author specifically delineates the Son as the sole speaker of the Scriptural text. In the instance of Hebrews 10 as well, he is speaking to God the Father displaying an attitude of trust with the aim of redeeming creation, only this time the author can depend upon his intervening argument to inform Jesus’ lines.

Verse five begins with a dio, “therefore,” indicating that the author relates Jesus’ speech (“he says”) to the previous statements. Here he speaks in response to the ineffectiveness of animal blood with regard to sin. It is not as if this shortfall is a surprise to God. This system was a shadow of the good things that would come (10:1).

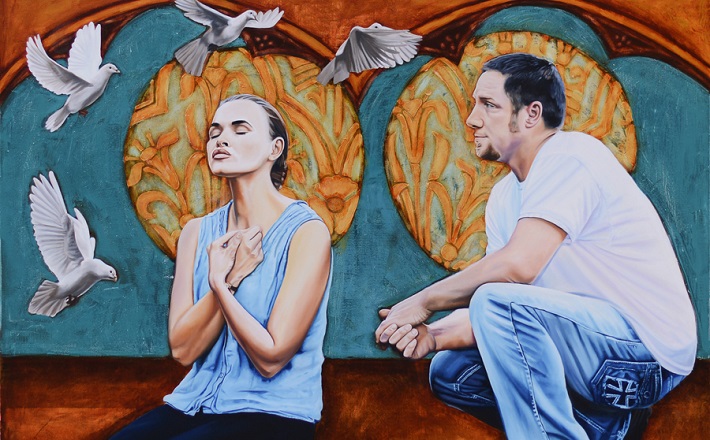

Shadows are less valuable when compared with the reality that casts the shadow, but at the same time they are helpful in that they are a forewarning — a foreshadowing, indeed — that something or someone is approaching. For the author of Hebrews, the sacrificial law is like the approaching shadow of the body of Jesus the Messiah. When he takes the place of his shadow, he is ready to speak — something a body but not a shadow can do.

The setting of his speech

Another pressing question arises with the author’s introduction to his speech: what is the setting of this speech? Its occurrence is related to his “entering into the cosmos” (10:5). Of the fifteen occurrences of “entering in” in the sermon, the other fourteen fall into two groups: “Entering into” God’s rest or “entering into” God’s sanctuary, both of which have an “on earth” and an “in God’s direct presence” component. Here the entry is into the cosmos which indicates for the author God’s creation (4:3) that became tainted by sin (9:26; 11:7, 38).

All the enterings are connected. The Son’s entering into the cosmos was followed by his entering into God’s sanctuary (6:19–20) so that others could enter into God’s rest (4:1, 6, 10, 11). This participle “eisercomai” could indicate then the cause of his speaking: “he says these things because he is entering God’s sinful world so that members of that world can enter God’s restful sanctuary or sanctified rest.”

The participle could also be an indicator of time. As a present participle, it would show that he is making this speech as he is entering the world. This would align with previous descriptions of the Son: 1) that he took on flesh and blood (2:14-18) — His entrance into the world is his becoming human — and 2) that he existed as a personal agent who could speak before he took on flesh and blood — the Son was with God before the creation of anything (1:2, 10).

Hebrews 1 may allow for the personal pre-existence of the Son, but Hebrews 10 confirms it, for if the entrance into the world is as a human member of the tribe of Judah (7:14), it would strongly imply a human birth. A newborn infant wouldn’t normally utter the words of Israel’s Scriptures at first cry. If these words are spoken by him “as he is coming into the world” they are spoken by a sentient being before he takes on the human condition from his conception. It is not surprising that commentators through the centuries have found the seeds of Jesus’ eternal divinity in the author’s introduction to the Son’s words.

The content of his speech

The author of Hebrews places the text of Greek Psalm 39:7-9 (Hebrew Psalm 40:6-8) on the lips of Jesus. The textual history here is complicated with manuscript variants in the Hebrew, between the Hebrew and Greek Septuagint, between the Septuagint and Hebrews, and in different copies of Hebrews itself. The major difference turns on one word: wtia (ears) or swma (body). Did God restore the speaker’s ears or prepare the speaker’s body? Clearly the body version serves the author’s assertions about Jesus the Messiah. Having taken on flesh and blood, his body is what brings sanctification (10:10).

The Psalm as a whole raises the juxtaposition of ritual vs. the heart. Readers might be tempted to interpret God’s lack of desire and pleasure for sacrifices as a rejection of ritual writ large. God wants one’s heart not one’s stuff. But the juxtaposition is not a simple example of either/or. David, to whom the Psalm is attributed (Psalm 40:1), cares deeply about setting up right sacrifice to God, but in this moment of having been redeemed, his primary concern is to proclaim God’s redemption. Sacrifice without testimony would have stolen an opportunity to proclaim God’s glory, but that is not to say that sacrifice wouldn’t have followed testimony.

So too with Jesus as the speaker of the Psalm. It is not that sacrifices and whole burnt offerings are bad in and of themselves, but they were not the will of God that Jesus came to enact. The author has already said that Jesus would not have been a priest on earth because, being from a non-priestly tribe (Hebrews 7:14), he would not have had any gifts to offer (Hebrews 8:4). His job — like the Psalmist — was first to proclaim God to others (Hebrews 2:12) and then to sacrifice. The blessed difference is, of course, he followed his testimony not with offering the flesh of animals, but by offering his own flesh.

The reason for his speech

The time of the shadow has now passed, the author proclaims. The Son has removed the first to establish the second (10:9). The previous instance of “first” and “last” language appeared in the author’s discussion of the covenants (8:7), so that very well could be the referent for the non-specified ordinals here. More immediately, they could refer to the pair discussed two times through the Psalm: offerings and God’s will. Jesus, by approaching, has removed the shadow, the sacrificial system, to establish the will of God which the shadow previewed.

In the next verse the author speaks of God’s will and our sanctification but notice that these are not equated. Instead, sanctification is the result of God’s will, not precisely the will itself. The next phrase clarifies; “By God’s will we are sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus the Messiah once for all” (10:10). God’s will, then, is the Son’s embodiment. The will of God is that God the Son take on a body, offer that body, and procure holiness. In so doing, he brought the foreshadowing of offerings to an end and he began the process of holistic sanctification. God’s command to offer the bodies of animals foreshadowed the offering of the human body of God.

December 23, 2018