Commentary on Luke 17:11-19

Ten men with leprosy are healed but only one returns and gives thanks.

This sounds like a lesson from almost every parent of a two year-old. “Don’t forget to say thank you, sweetheart.” To be sure, giving thanks for gifts received is always a good thing — O give thanks to the LORD for God is good, God’s mercy endures forever (Psalm 106:1). However, when considered within Luke’s wider narrative, there is much more to be heard from this passage than a simple morality tale designed to improve the social graces of Jesus’ followers.

Jesus in borderlands and unsafe territory

Jesus’ encounter with the lepers takes place in the “region between Samaria and Galilee,” suggesting a potentially hostile locale at the border, neither inside nor outside Jewish territory. Jesus is on the way to Jerusalem, a literary road sign that points ahead to the impending violence of the cross. It also points backward to the beginning of the journey (Luke 9:51ff), which, as we will see below, includes another reference to Samaritans.

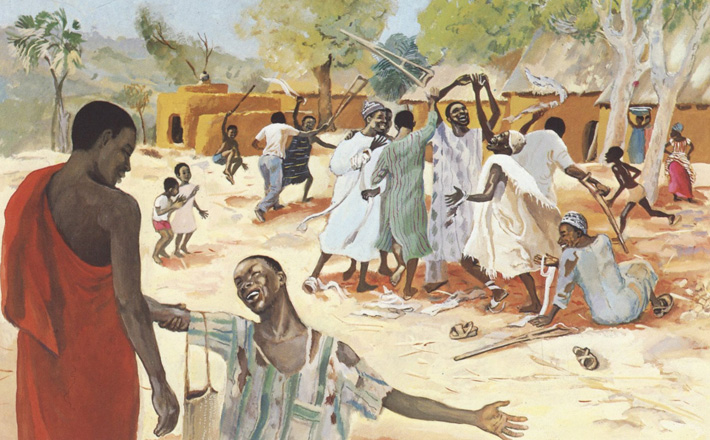

The relationship between Samaritans and Jews at the time of Jesus was conflicted and sometimes violent. Centuries before this they had been one people, but changes and tensions wrought by exile and return put them at odds regarding beliefs about scripture, worship, what it means to be holy, etc. A history of hostility may explain why James and John suggest firebombing a Samaritan village (“Lord, do you want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?” cf. 2Kings 1:10-12) after it refuses to serve as the first rest stop on Jesus’ journey. Jesus firmly rebukes their violent request (Luke 9:51-56).

In any case, despite potential danger, and without asking anything about their loyalties, heritage, or intentions (will they perpetuate the hostility?), Jesus works healing for all ten — including the Samaritan.

Jesus offers mercy to foreigners/outsiders

At the beginning of his ministry, Jesus extends his mission beyond the boundaries of his homeland. He reminds the assembly “there were also many lepers in Israel in the time of the prophet Elisha, and none of them was cleansed except Naaman the Syrian” (Luke 4:27). In response his townspeople seek to throw Jesus over a cliff (Luke 4:30). It can be difficult to accept the welcoming ways of God.

The Old Testament episode to which Jesus alludes (2 Kings 5:1-15) is an alternate reading for this week. Its reference in Luke, like footage from a movie trailer, previews our pericope and suggests that (1) outsiders too are recipients of God’s work in Jesus; and (2) there is something to be learned from them.

The stories of Naaman and the Samaritan share common details. Of course there is the fact that both refer to Samaria and concern healing from leprosy. Naaman (a Syrian) and the Samaritan both are foreigners: outsiders to the people of God. Naaman is even commander of an army that opposes Israel. Even so, God heals each from leprosy, despite their enemy/outsider status, before they pledge any allegiance to God. Both are healed from afar (without being touched). Both return to the source of their healing, and both are sent along their way with a command to “Go.”

Whatever are God’s criteria for showing mercy — demonstrated through Elisha and Jesus — they seem considerably more generous than our own norms, then and now.

Indeed, by way of repetition Luke focuses our attention on the outsider/foreigner status of one who returned to give praise to Jesus. First Luke notes that he is a Samaritan (v. 16), and then Jesus refers to him as a foreigner (v. 18). Like the “good” Samaritan of Jesus’ parable (yet another reference to Samaritans found only in Luke 10), God’s mercy is not limited by human conventions regarding insiders and outsiders — even when the outsider is an enemy.

Noticing that Jesus is worthy of praise

In a prior episode concerning a man with leprosy (Luke 5:12-15), the healing itself receives literary attention. Jesus stretches out his hand and touches the man, announces his intention to heal, and then says be clean. As proof of healing, Luke writes, “immediately the leprosy left him” (Luke 5:13).

In the case of the ten, in contrast, the healing itself is not narrated, but only its outcome. Nor does Jesus comment on the men’s obedience, even though their healing occurs as they do what Jesus commanded. This suggests that healing and obedience per se are not really the focus of the episode.

After the Samaritan saw that he was healed, the rest of his response is characterized by four verbs: turn back (hypostrepho), praise (or give glory; doxazo), prostrate (literally fall on his face), and thank (eucharisto). Jesus highlights the first two verbs by repetition: “Was none of them found to return (hypostrepho) and give praise (doxa) to God except this foreigner?”

Return and praise play significant roles in Luke. At Jesus’ birth the shepherds “returned (hypostrepho), glorifying (doxazo) and praising God for all they had heard and seen … ” (Luke 2:20). After witnessing Jesus’ ascension, in the last two verses of this Gospel, the disciples “worshipped him and returned (hypostrepho) to Jerusalem with great joy and were continually in the Temple blessing God” (Luke 24:52). Return and praise frame this Gospel, suggesting a road map for our response to God’s activity in our world.

“Get up and go!” with the promises of God

The passage ends with a command to the Samaritan: “Get up (anistemi; rise) and go (poreuomai) on your way; your faith has made you well.” When it appears in Luke-Acts the phrase “get up and go,” suggests that a significant (even wondrous) change is about to occur. After the annunciation, for example, Mary “gets up and goes” to Elizabeth (Luke 1:39). The prodigal son decides to “get up and go” back to his father (Luke 15:18), and God tells Paul to “get up and go” to Damascus (Acts 22:10; cf. Acts 9:11; 10:20).

The command to get up and go comes with a promise to the Samaritan: “your faith has made you well (literally saved you).” The good news of this encounter carries with it the promise that through Jesus, God empowers people to step across boundaries, share mercy with outsiders, pay attention to things worthy of praise and move forward into God’s future with assurance that there is more to God’s story than meets the eye. For that, may we always give thanks.

October 9, 2016