Commentary on Luke 12:13-21

The parable of the rich fool (or “barn guy,” as I always think of him) at the heart of this week’s text illustrates simply and memorably the futility of choices made in isolation from the love of God and neighbor.

It reflects a central theme in Luke and in Jesus’ preaching, the problem of wealth in the context of the holy kingdom where closeness to God is life and attachment to things reflects soul-stifling anxiety and fear.

The parable emerges from Jesus’ response to a request from someone in the immense crowd of Luke 12:1 that Jesus arbitrate between him and his brother in the matter of an inheritance. Jesus not only denies the request but makes it the basis for a warning against greed and a reliance on wealth for security of the soul (Psalm 49, another lectionary passage for this Sunday, has a similar message; see also Colossians 3:2, 5). Inheritance, greed, and accumulation of wealth all figure in the parable and in its interpretation in the verses that follow the lectionary text (Luke 12:22-34); these verses are linked to 12:13-21 by the word “therefore” and by the focus on what makes for life (the word translated “life” there and in 12:20 is translated “soul” in the inner dialogue of the rich fool in 12:19), a connection reinforced by references to barns, treasure, possessions, and eating and drinking. Luke 12:22-34 never appears in the lectionary, so it is worth including it in this Sunday’s worship, if possible, but even if it isn’t read, it should be taken into account as part of Jesus’ response to the problem raised by the brother in the crowd and as the antidote to the predicament of the greedy fool.

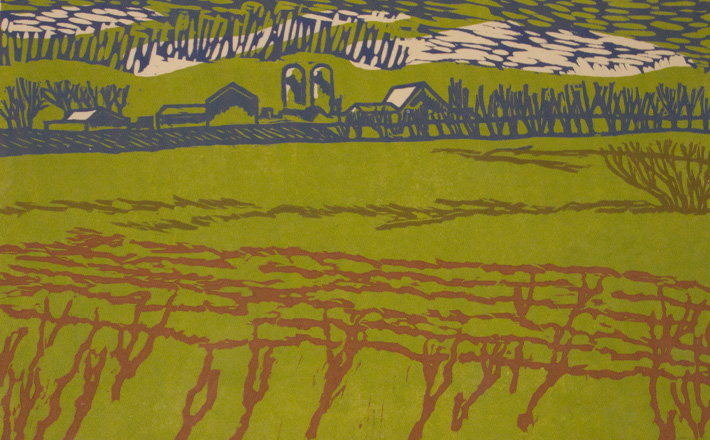

At the heart of the parable is an abundant harvest, which might be a good thing, but we suspect from the start that this is unlikely because we know from Jesus’ introduction of the landowner that he is rich. The best hope Luke offers the rich in this Gospel comes in the story of Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1-10), who seeks out Jesus and then welcomes him enthusiastically when Jesus invites himself home with Zacchaeus for dinner. While everyone is grumbling that Jesus is off with sinners again, Zacchaeus promises to give half his possessions to the poor and to pay back anyone he has defrauded fourfold. Zacchaeus is a special case among the rich of Luke in that he is also a member of a marginalized group, tax collectors, who are portrayed sympathetically throughout and treated kindly by Jesus. Other references to the rich are almost uniformly negative and almost always contrasted with positive references to the poor: God sends the rich away empty in Mary’s prophetic poetry (Luke 1:52-53); they have “a woe on them” (as a cousin of mine used to say) in the beatitudes (6:24), where the poor are given the kingdom of God; they are portrayed as beyond hope in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, where in response to the rich man’s request that Lazarus be sent to warn his brothers, Abraham says that if they haven’t listened to Moses and the prophets, they won’t be convinced “even if someone rises from the dead” (16:31); and finally the very rich ruler seeking the way to eternal life lacks only one thing, that he sell his possessions and give the money to the poor, and that appears to be the one thing he cannot do. It is nearly impossible for the rich to enter the kingdom of God, Jesus concludes (18:24-25), but he ends the episode on a note of hope (18:27): “What is impossible for mortals is possible for God.”

That is the situation for the rich of Luke’s Gospel, so we are not hopeful about how the rich landowner will handle his abundance. Confronted with the happy problem of a bumper crop, he consults with himself, with no thought of God or neighbor, and concludes that the answer is to build bigger barns for his crops and his other goods. Then he looks forward to congratulating his soul on this decision, as he and his own soul with all that accumulated wealth spend many happy years eating, drinking, and making merry.

God, overhearing the rich man’s conversation with himself, cuts short these dreams of merriment: “Fool,” says God. The word occurs elsewhere in Luke only in Luke 11:40, with reference to the Pharisees; there too foolishness is associated with greed and with the neglect of justice and the love of God. In our text, there is no time for the rich fool of the parable to make amends because his soul/life is coming to an immediate end, which no amount of accumulated wealth can forestall. “And whose will it all be then?” God asks, returning to the notion of inheritance raised by the brother in the crowd but from another angle. Jesus concludes that this is how it always is for those who store up treasures for themselves but are not rich toward God. The two notions, storing up treasure and being rich toward God, are verbal forms with the same roots as the noun “treasure” and adjective “rich.” In other words, it isn’t a question of something we happen to have or a characteristic among many. We actively choose to do one thing or the other, to be rich with barns or rich with God, to serve God or mammon (Luke 16:13).

Like the story of the rich ruler where God’s grace has the last word, so here also Jesus’ teaching ultimately transcends the greed and God-less treasure of the parable to move in a hopeful direction with Luke 12:22-34. With a shift in perspective, we lift our eyes up to the birds and out to the lilies of the field. We turn away from treasure that corrupts and is corruptible toward the kingdom and fullness of life, which we already know from Luke 10:25-37 is rooted in wholehearted love of God and neighbor. In this alternative message about God’s faithfulness, Jesus recognizes that what underlies excessive accumulation is most often anxiety and fear. So Jesus offers the antidote to accumulation of too much empty treasure in the promise that it is the Father’s good pleasure to give the kingdom itself to his little flock. And the way to collect treasure of the heart suitable for that kingdom isn’t the earthbound, inward-looking way of the barn guy but the soaring, beautiful way of the one who lives and loves generously, lavishly, and with joy.

July 31, 2016