Commentary on Luke 2:41-52

Christians sometimes refer to Jesus’ growing-up years as a model for human growth and development.

The Christmas hymn, “Once in David’s Royal City,” for example, contains the stanza,

Jesus is our childhood’s pattern,

Day by day like us he grew.

He was little, weak and helpless,

Tears and smiles like us he knew.

Thus he feels for all our sadness,

And he shares in all our gladness.

(Cecil F. Alexander, “Once in David’s Royal City,” Chalice Hymnal [St. Louis: Chalice Press, 1995) 165

While we can assume that the infant Jesus was weak and helpless, cried and smiled, and grew from infancy through childhood and youth to adulthood, the gospels themselves are almost silent on those years. The theological purposes for recalling Jesus’ growth in this frame of reference are often twofold — to assure congregations that Jesus fully understands the depths and heights of the human experience and to use Jesus’ growth as a model for Christian education as well as for rearing children in the home.

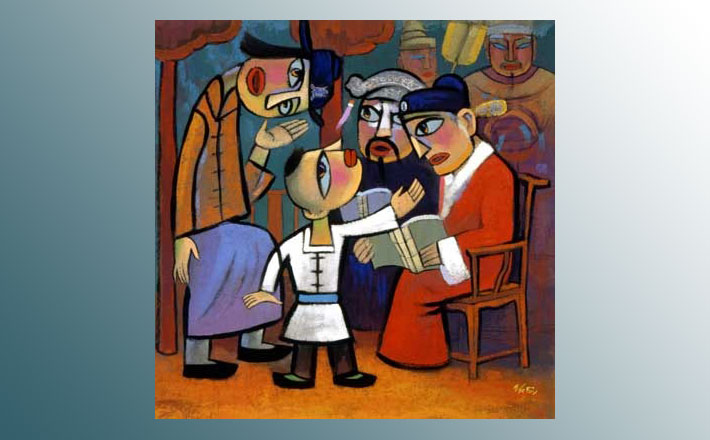

Luke’s story of Jesus in the temple at the age of 12 is the only incident in the gospels about the life of Jesus between infancy and the beginning of his ministry. Luke has several intentions for this passage in the gospel of Luke and the book of Acts that are suggestive for preaching. While these motifs intersect with the themes just mentioned, they do not simply validate them in a one-to-one fashion. The latter themes are theologically important regardless of whether Luke (or other biblical writers) have them in mind.

When recounting the lives of major figures in antiquity, ancient literature often included stories of unusual births and remarkable childhood feats. Ancient people regarded such stories as evidence that the gods had a special guiding role in the lives of such figures. Luke’s birth and childhood narratives play this role (among others): assuring listeners that the hand of God guided Jesus from the beginning.

This ancient function might prompt the preacher to a contemporary consideration. What things give today’s congregation reason to trust Jesus and to commit ourselves to the way to the realm?

By noting that Mary and Joseph went every year to Jerusalem for the Passover, Luke 2:41-52 implies that Jesus grew up in a faithful Jewish household. The emphasis on Jesus in the temple and his interaction with the teachers of Israel plays a similar important role in the gospel of Luke and the book of Acts. Jesus was immersed in Judaism since his youth. He speaks as an insider with a thorough knowledge.

These facts are important because by the time Luke wrote (80-90 CE) tensions had developed between Luke’s congregation, whose distinguishing features were believing that the ministry of Jesus began the final and full manifestation of the realm of God and welcoming gentiles into the community without complete conversion to Judaism, and other Jewish groups that did not share that belief.

As the ministry of Jesus unfolds, Jesus has considerable conflict with Jewish authorities over how to interpret God’s presence and purposes in the eschatological moment. The same thing is true of the church in Acts. By recollecting that Jesus was raised in a faithful Jewish atmosphere, and recalling that Jesus speaks as a Jewish insider, Luke assures listeners that the viewpoints of Jesus and the church are authentically Jewish. Jesus and the church do not reject Judaism. They interpret Jewish convictions in light of the eschatological turning of the ages.

At one level, a preacher could use this theme as the beginning point to reflect with the congregation on its perceptions of, and relationship with, Jewish communities today. A sermon could help the congregation reflect on the degree to which anti-Judaism or even anti-Semitism may touch life of the congregation and of the larger world. Taking another step, a preacher might help the congregation consider shared mission with the synagogue down the street.

At another level, today Christians often find themselves in disagreement with other Christians. One Christian group sometimes proclaims the Christian way and condemns as unchristian those who hold to other interpretations. A lot of people trying to follow Jesus — especially in the historic churches — are confused as to what might be authentically Christian. If the congregation finds itself in such a situation a preacher might begin with Luke 2:41-52 as an analogy in a sermon in which the preacher assures the congregation of their Christian identity similarly to Luke’s assurance of his earlier congregation.

It is easy to be appalled that Mary and Joseph lost track of Jesus. Luke, of course, is not pointing to bad parenting, but is setting the stage for Jesus to state clearly his own understanding that he has a special relationship with God. God is Jesus’ parent (not Joseph), and Jesus is to be about God’s interests, i.e. must serve God’s purposes.

This notion raises a possibility for preaching. Many people today are confused about identity and vocation, about who they are and their mission in life. This is particularly (though by no means exclusively) true of Millennials. It may go too far to say that Jesus here claims his own identity and mission. Whether or not that is exegetically true, this passage could provide the preacher with an entry into the importance of claiming our own identities as disciples and witnesses in 2016.

In the gospel of Luke and the book of Acts, Jesus is the model for the apostles who are the leaders and models for the church. In the broad sense, then, the last line of this passage is a model for Christian education and child raising: to encourage children to increase in wisdom and in stature (the latter a preferable translation to “years”). Wisdom and statue refer to the capacity to discern God’s realm purposes and to respond accordingly.

December 27, 2015