Commentary on 2 Kings 2:1-12

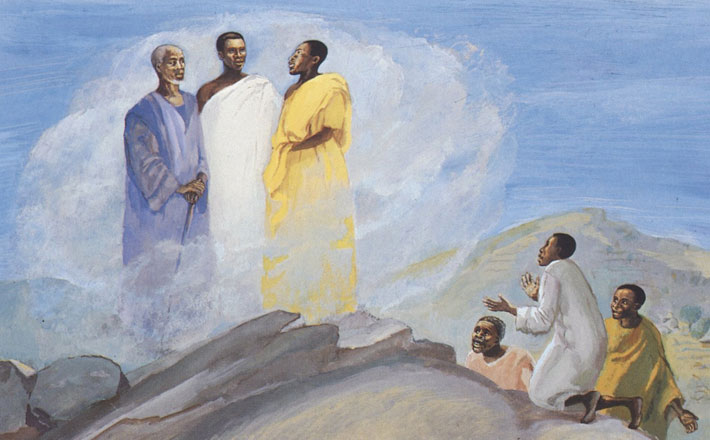

The story of Elijah’s ascension to heaven in a whirlwind is paired in the lectionary with the Transfiguration of Jesus.

In the larger context of the New Testament passages, one can see the efforts of both the disciples and the Gospel writers to understand Jesus in light of the Old Testament (OT). Jesus asks the disciples who the people say he is, and they tell him that he is identified with John the Baptist, Elijah, Jeremiah, or another of the OT prophets (Mark 8:28; Luke 9:19; Matthew 16:14).

John the Baptist and Jesus were frequently identified with OT prophets and other figures who were thought to have had special revelation from and contact with God. Indeed, Elijah was not the first figure in the biblical narrative to have been taken to the heavens. It is similarly recounted of Enoch that he “walked with God,” but “then he was no more, because God took him” (Genesis 5:24). This was interpreted to mean that Enoch had not died, but had gone to be with God, and he was therefore viewed as a kind of supernatural sage. In the intertestamental period, apocalyptic books were written about his heavenly journeys and visions (1-4 Enoch), and Hebrews 11:5 reflects this same set of ideas: “By faith Enoch was taken so that he did not experience death.”

Outside of the New Testament (NT), it is Enoch and Elijah who are most commonly presented as harbingers of the messiah, but the NT pairing of Moses and Elijah may draw on Malachi 4:4-6, which warns its hearers to prepare for the coming Day of the Lord: “Remember the teaching of my servant Moses, the statutes and ordinances that I commanded him at Horeb for all Israel. Lo, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the LORD comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse.” Moses and Elijah here seem to symbolize the law and the prophets, which Jesus embodies and fulfills for his followers (see Matthew 5:17-18).

Elijah is “taken” (2 Kings 2:3-10; 1 Maccabees 2:58) while still living, and so the beliefs and expectations surrounding his role were much the same as for Enoch, with the aforementioned prophecy of Malachi serving as a crucial prooftext (Sirach 48:10). In later Jewish tradition, Elijah’s return is expected, and a chair or cup is set for him at various gatherings.

In the Christian tradition, however, John the Baptist is usually identified as the second coming of Elijah. Matthew 11:13-14 reports that “all the prophets and the law prophesied until John came; and if you are willing to accept it, he is Elijah who is to come,” while in Luke 1:17 the angel Gabriel tells Zechariah that John will go before Jesus “with the spirit and power of Elijah.” In the Markan and Matthean accounts, Jesus still has to explain the significance of Elijah to his disciples. In Matthew, they ask, “Why, then, do the scribes say that Elijah must come first?” and Jesus answers, “I tell you that Elijah has already come, and they did not recognize him, but they did to him whatever they pleased. So also the Son of Man is about to suffer at their hands. Then the disciples understood that he was speaking to them about John the Baptist” (Matthew 17:10-13).

The scene of Elijah’s ascension is far more elaborate than others, as “a chariot of fire and horses of fire separated the two of them, and Elijah ascended in a whirlwind” (2 Kings 2:11). Elisha cries out, “Father, father!” — not meaning a biological relationship, but rather using common ancient Semitic kinship terminology towards a superior figure (e.g., Genesis 45:8; 1 Samuel 24:11; Judges 17:10). He goes on, “The chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” — drawing on the ancient image of YHWH as the commander and chief charioteer of the heavenly host (Psalm 68:4, 17 [ET]). The Lord has come to pick Elijah up, or at least sent his heavenly host for him. The same words are cried out by Jehoash, king of Judah, as Elisha’s death is near (2 Kings 13:14); in the latter case, it is presumably an invocation of God to come down and take Elisha up. The repetition of the phrase gives the impression that it may have been a relatively common saying, and gave rise to the popular spiritual, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which longs for divine deliverance and comfort: “a band of angels, a-comin’ after me — comin’ for to carry me home.”

In Matthew 16:13, Jesus identifies himself with the Son of Man; none of the aforementioned Old Testament figures is ever called “Son of Man,” which indicates another intertextual association. Both Ezekiel (passim) and Daniel (8:17) are called “son of man” (Hebrew ben ?adam), and both of them are supernaturally transported and offered revelatory visions. Daniel also sees “one like a son of man (Aramaic bar ?enaš) coming with the clouds of heaven,” to whom “was given dominion and glory and kingship” (Daniel 7:13-14).

One crucial feature of 2 Kings 2 is that it validates Elijah’s authority before his witnessing successors. A divine decision to take Elijah up to heaven makes him a rare figure indeed. The New Testament authors certainly recognized his significance, since the only figures mentioned more often were Moses, Abraham, and David. The fact that Elijah had disciples also made him an apt figure for Jesus. Although some other OT prophets such as Isaiah (Isaiah 8:16) seem to have had followers, we certainly cannot say this was the norm for prophets who came after Elisha.

There are significant structural differences between 2 Kings 2 and the stories of the Transfiguration, however; most notably, Elijah departs from Elisha and his disciples, whereas Jesus returns to his. The Elijah story would be more naturally read in conjunction with Jesus’ Ascension (Acts 1), since it marks a similar transition of earthly leadership. Elisha asks “let me inherit a double share of your spirit” (v. 9), and indeed he picks up Elijah’s mantle and proves able to carry out the same miracle of dividing the waters. Jesus seems to expect his followers to be able to carry out the same wonders he did, if not greater ones (John 14:12). Many churches since have not reflected seriously enough on what it means to inherit Jesus’ miraculous (and prophetic) ministry.

February 15, 2015