Commentary on Psalm 15

There are two divergent ways to think about Psalm 15.

We can regard it from a historical point of view, understanding its place in Israel’s worship life; and we can weigh its content from a theological, even personal perspective. The first is far more pleasant.

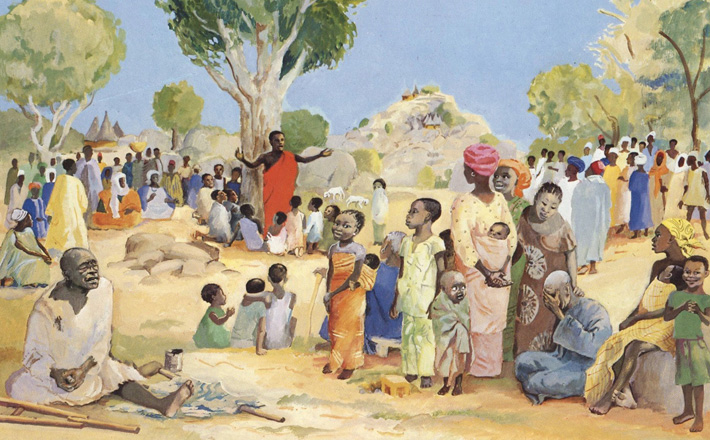

A cluster of other Psalms, especially Psalm 24 but also Psalms like 47, 84, or 150, tell us about Israel’s liturgical life, and shed light on Psalm 15. Pilgrims have made the arduous journey in caravans to the Holy City for one of the great festivals. The time draws near for the worshippers to enter the temple precincts. The Ark of the Covenant would be hoisted up high, trumpets would blare, and a Q&A between the priest inside the gate and the crowd pressing to come in would ensue.

Who indeed may abide in God’s tent (a figurative image, left over from the days of the tabernacle in the wilderness)? The priest’s reply underlines the importance of holiness, that God isn’t to be trifled with, that you wash in the ritual bath before you enter this place of sanctity: “Those who walk blamelessly,” and so on.

Historically this is fascinating. But I wonder what then enabled any one of them to feel they could actually stroll into the place? What pressure is there in these requirements? Walk blamelessly, stand by an oath even if it hurts, do not slander with the tongue, nor reproach their neighbors? We are masters of rancor, and even feel some smug self-righteousness when we blithely point out the woes in other people.

The Psalm says those who loan money at interest can’t come in. If we adhered to this, capitalism would come to a screeching halt! And all these “requirements”? Isn’t God all about mercy and grace? Or at least forgiveness? Who is worthy? No one is worthy — or only Christ himself was worthy.

Perhaps we think Christologically and imagine what Karl Barth might have said — that it is Jesus, bearing our humanity, who can faultlessly enter God’s holy place in our stead, even pioneering the way for us to ride in on his coattails. But perhaps we reassess how thoughtlessly we presume upon the presence of God. We live any old way that suits us — and then dare to come into worship as if all is well? Do the stringent requirements for those who would even step across the threshold tell us to stay away? Or rather to enter as those who know they are guilty, and in dire need of mercy, cleansing, and even healing of heart?

Instead of “Who can enter God’s holy place?” we might even ask, “Who can leave God’s holy place?” Hopefully not those who are no different from the way they were when they walked in the place (as in the old joke about the service ending as the people sing multiple stanzas of “Just as I am,” and some come forward just as they are, and then when it’s over, they exit the place just the way they were).

God’s will, the Torah of the Lord, Jesus’ teachings, the rules of the church: all this should exist, not to keep us in line, or to dole out guilt, and certainly not to function as leverage for the institution to keep itself fed. Divine law, if it is truly divine, is for our well-being; the God who made us and designed the whole order of creation in love knows what will bring joy to us. The Psalm’s last line is its best line: “Those who do these things shall never be moved.”

Stability, not being thrown off balance, able to weather the storm: virtue exists so we might not tremble with anxiety or be blown hither and yon over every little thing. It is only the deeply cultivated life, deliberately and in a disciplined way in sync with God, that can be non-anxious, reliable, deeply rooted. Mark Helprin, in Winter’s Tale, wrote these profound words:

Little men spend their days in pursuit of small things. I know from experience that at the moment of their deaths they see their lives shattered before them like glass … Not so, the man who knows the virtues and lives by them. The world goes this way and that. Ideas are in fashion or not, and those who should prevail are often defeated. But it doesn’t matter. The virtues remain uncorrupted and uncorruptible. They are rewards in themselves, the bulwarks with which we can protect our vision of beauty, and the strengths by which we may stand, unperturbed, in the storm that comes when seeking God.1

Worship is the womb in which virtues are born, and it is virtue that empowers the worshiper to draw ever closer to God. Mercy is required for such virtue — but these three, virtue, mercy and worship, are how we abide in God’s holy tent.

1 Mark Helprin, Winter’s Tale (NY: Pocket Books, 1983), 252-253.

February 2, 2014