Commentary on Isaiah 52:13—53:12

In the history of Christian interpretation of the Old Testament, few texts are more revered than Isaiah 53.

The descending and ascending scales of Handel’s Messiah are embedded in the hearts and souls of many English-speaking parishioners. Even as I write this paragraph, a baritone’s voice is singing in my mind, “Surely, surely he hath borne our griefs and carried our sorrows.”

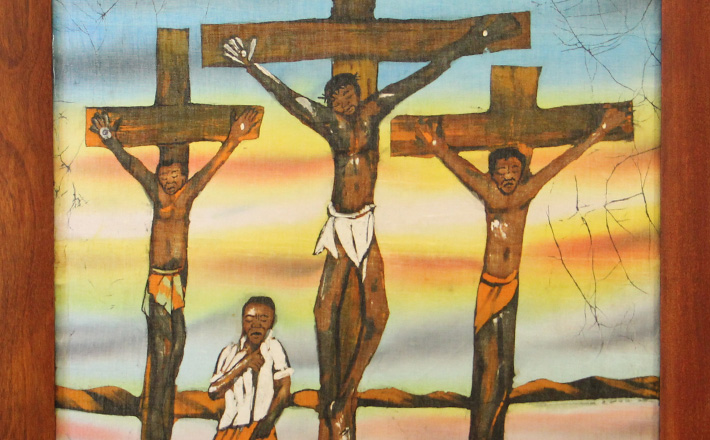

The text’s liturgical placement on Good Friday also makes it nearly impossible for Christian readers of Isaiah to read Isaiah 53 in any other way than as a witness to the atoning work of Jesus Christ. The images of the rejected man of sorrows, suffering in isolation as he endures the blows of God for our iniquities seem ready-made for Christian reading.

As revered as Isaiah 53 is, few texts are more hotly contested in the scholarly world. Interpretive battles abound over the identity of the servant, the original intention of such a text, its form-critical setting in Judah’s exilic and post-exilic period, its reception in the inter-testamental period, and all these without mentioning the numerous textual-critical difficulties in the Hebrew text (Lord, help us with 53:10!). While affirming the numerous matters needing attention in this text, I will ask the reader’s indulgence if I sidestep many of these issues and simply read this text as the church has done since its inception, namely, as an enduring witness to Jesus Christ and his work.

The Ethiopian eunuch sat on the back of his chariot reading Isaiah 53 in dismay (Acts 8:26-40). Philip asks him, “Do you understand what you are reading?” The eunuch responded, “How can I unless someone explains it?” Then beginning with this Scripture, Philip explained the good news of Jesus Christ. Speaking of this episode in Acts 8, Gerhard Sauter reflects on the nature of faith in the process of reading Scripture: “Faith does not work, like a pair of glasses, however, that allows us to decode the text; glasses can be taken on and off. Faith, on the other hand, is constitutive, like the retina, which makes sight possible in the first place but can only cast an image of what is real!”1 Faith provides for us the very eyes needed to read such a text in its full witnessing potential.

The cause of the servant’s suffering is poignant and straightforward: our infirmities, our diseases, our transgressions, our iniquities. Place-taking is an offensive idea in the modern west. Kant put the matter bluntly: it is irrational and impossible for the guilt of one party to be transferred to another. But the logic of the Scriptures demands a different account of the matter. The vicarious humanity of Christ in both his life and death is a central metaphor for God’s act of reconciliation.

In the language of verse 5, he took our blow so that we could have peace (shalom). The innocent one, spotless and free of guilt, is standing in the place of others. He did so both by identifying himself with sinners — he made his grave with the wicked; he was numbered with the rebellious (53:9,12) and by taking their guilt on himself in innocent suffering — it was the will of the Lord to crush him; he shall bear their iniquities; he bore the sin of many (53:10-12).

These are heavy verses of Scripture. They bring before us an acute consciousness of our own sin and rebellion. These words are not laced with therapeutic attempts at self-help. They reveal us as we truly are, even if our consciences do not bother us; even if we do sleep peacefully at night. “All we like sheep have gone astray.” Whether recognized or not, our state is a precarious one when standing before the suffering servant on this Good Friday. While at the same time, beauty arises out of the ugliness. Hope emerges from the horror. We might call it the ugly beauty of God’s ultimate act of reconciliation. “While we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). When we stand before the cross we see perfection itself suffering for transgressors like me.

As we saw in Isaiah 50:4-9, the servant is confident of his ultimate vindication. Isaiah 53:10 reveals the servant confidently looking forward to the seed promised him on the far side of his suffering and death. His days cut short by death will be prolonged in the offspring made righteous on account of his work. “Out of his anguish he shall see light.” Mourning yields to rejoicing. Or in the words of Hebrew 12, it was for the joy set before him that endured the cross, suffering the shame and despising the loss. Such love for sinners on this Good Friday causes us to put our hands over our mouths as we lift our hearts to the Lord.

George Herbert’s (1593-1632) oft-quoted poem “Love” makes effective the point.

LOVE bade me welcome; yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lack’d anything.

‘A guest,’ I answer’d, ‘worthy to be here:’

Love said, ‘You shall be he.’

‘I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on Thee.’

Love took my hand and smiling did reply,

‘Who made the eyes but I?’

‘Truth, Lord; but I have marr’d them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.’

‘And know you not,’ says Love, ‘Who bore the blame?’

‘My dear, then I will serve.’

‘You must sit down,’ says Love, ‘and taste my meat.’

So I did sit and eat.

1Gerhard Sauter, Protestant Theology at the Crossroads: How to Face the Crucial Tasks for Theology in the Twenty-First Century (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 38.

April 6, 2012