Commentary on Luke 14:1, 7-14

My family sits down together at dinnertime most evenings.

It’s a time to catch up with the activities of the day, as well as just a respite from the busyness of life. No texting is allowed at the table. It’s important for us to touch base with one another in this way to ensure that all is well with, in our case, our four sons.

When our oldest son is home from college, the noise level is loud and the six of us are usually talking at the same time. There’s a lot of laughter and if one of us has a good story or joke to share, then all of us tune in. On the more serious side, it’s a time to make decisions as a family and, on occasion, to put family pressure on one of our sons who may be about to make a serious ethical decision. Character building and value shaping are central, even if not plotted, to the time we share together around the evening meal.

Commentary

Jesus, too, is interested in mealtime. Jesus loved the gatherings around meals; at least, that’s what we are led to believe in the Gospel of Luke. This was one of the primary distinctions between him and his ascetic mentor John the Baptist. He doesn’t even deny the charge that he enjoyed more than his share of wine at many meals (cf. 7:33). In our story, Jesus is at a banquet and tells a “parable” about the meal setting, which is followed up by another story about another banquet. He can’t get enough of what happens at meals.

On another note, it should not be surprising that Jesus shares a meal with some of the Pharisees. Once we remove the negative impressions we have of this formidable group and recognize their influence on many people during the first century, we should not be surprised by this encounter. Just a few verses earlier some Pharisees actually assisted Jesus by informing him of Herod’s plans to locate Jesus (cf. 13:31). This suggests a more neutral relationship between “the Pharisees” and Jesus in Luke’s Gospel.

By chapter 14, Luke has established a pattern of Jesus’ freer activity on the Sabbath. These Pharisees, not surprisingly, are “watching him closely” (14:1); perhaps it is due to what they have heard about Jesus’ Sabbath practices earlier (e.g., 6:6-11 and 13:10-17). Whenever this verb is used — “watching” from paratereo (“keep alongside”) — the religious leaders do not do this simply out of curiosity.

They are trying to trap Jesus, either in some activity like healing on the Sabbath (cf. 6:7) or something inappropriate he might say (cf. 20:20). But, here, after Jesus heals someone on the Sabbath, there is no little to no reaction to Jesus’ activity. Luke wishes to draw our attention elsewhere in this short story. He would like us to think about “meals” in first century life.

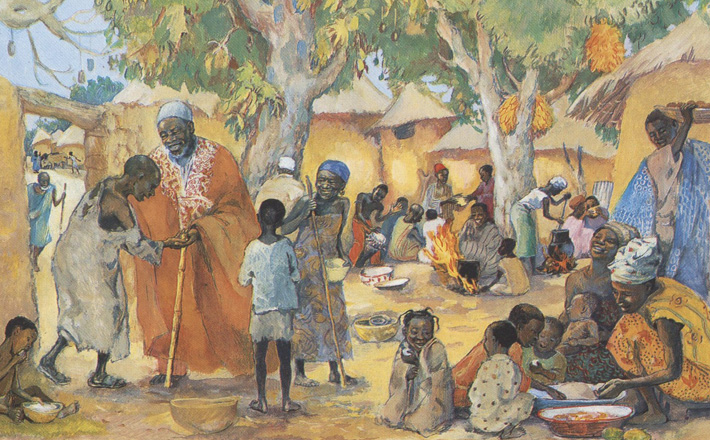

In the Gospel of Luke, meals, in particular, provide central settings for Jesus’ mission. And, the language of food, in general, serves as a basis for Jesus’ teaching (cf. 11:5-8; 15:14-17, 23; 12:16-21, 45; 17:7-10). Eating is a sign of life (cf. 8:55; 17:27-28; 24:43) and celebration (cf. 15:23). But it also symbolizes the harsh realities for the enslaved (cf. 17:7-10). Food has religious connotations as well (cf. 6:1-4; 7:33; 14:15; 22:14-20); Jesus “blessed” it (cf. 9:16; 22:19; 24:30) and prayed for it daily (cf. 11:3).

Even though Jesus shared several meals with Pharisees (cf. 7:36), they often complained about his choice of (other) table-fellowship companions (cf. 5:30) and about how his associates secured food on the Sabbath (cf. 6:1-4). Unlike his possible mentor (John the Baptist), Jesus loved food (cf. 7:33) and his disciples followed suit (cf. 5:33). Just as he expects to care for the physical needs of others (cf. 9:13), he expects that others will provide for his disciples when they minister among them (cf. 9:3; 10:7-8).

Indeed, he assumes that friends will share it (cf. 11:5-8; 24:30), which is a natural outgrowth of first-century Jewish culture. Theologically, he believes that God will provide for the basics of life, so he teaches and acts accordingly (cf. 12:29-31).

In Luke 14, Jesus is less interested in the actual food than in the composition of the banquet. So, he tells a story about meals and honor. It’s an unusual “parable” in light of its clear references. His story emphasizes two components of the banquet setting: (1) the selection of “seats” (honor?); and, (2) the invitation list. In an honor and shame culture, avoiding shame is of the utmost importance. This is not simply embarrassment. Public shame may have tangible implications for the shamed. A family’s bartering practices or marriage proposals can be negatively affected by a public shaming, if the shame is significant enough.

On the opposite end, public honor — determined, in this story, by the host — may come to those who express public humility. Jesus expresses expectations for hosts (cf. 14:12-14). His words are a challenge to the honor system embedded in first-century culture. To secure one’s place in this system, it was appropriate to invite friends, family, and rich neighbors. Reciprocal requests would ensue, as the public acknowledgement of an honorable person may bring its own rewards.

But Jesus calls into question this type of caste system, imagining instead hosts who choose to associate with people who are “poor, crippled, lame, and blind” (14:13) as their new network. The problem for hosts, however, as Jesus explicitly recognizes, is that no honor is forthcoming in return. Rather, it’s an investment in the future.

So what?

“One does not live by bread alone,” as Jesus argues in the temptation scene (4:4). Nor is Jesus only concerned about what happens at meals. His teaching is about the way we treat others, especially those among us who unable to “pay us back.” In a modern democratic society in which public political rhetoric emphasizes that all are (created) equal, it is easy to miss the emphasis of Jesus’ teaching in his own status-oriented, honor-shame and hierarchical space.

Yet, we have our ways of distinguishing one from another, in order to structure our contemporary world. Oftentimes, these distinctions among us hinder us from true fellowship with one another. Jesus’ story is a reminder to us about the company we keep. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. understood, “Our goal is to create a beloved community and this will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.”

September 1, 2013