Commentary on Joshua 5:9-12

Even though the Old Testament reading for this week is brief, it plays a critical role within the book of Joshua.

The two central events at Gilgal, circumcision and Passover, become the final acts of the nation prior to possession of the land. Clearly the author desires for the reader to understand them as preparatory events to what follows, preparing the people for possession, but also acknowledging the identity of this generation.

Nearly all translations and commentaries assign verse 9 to the pericope concerned with circumcision (verses 2-9), and rightly so, yet those compiling the lectionary have opted to read this verse with what follows. The question then for the interpreter is not “Should verse 9 be discussed?” but what does verse 9 have to do with verses 10-12?

Verse 9 operates as a concluding and perhaps summative statement of all that appears in verse 2-8. In verse 2, the LORD calls Joshua to “circumcise the Israelites a second time.” The Hebrew word šēnît can, and often does mean “a second time.” The term, however, can also mean “again.” In this case, “again” implies the reinstituting of the rite of circumcision after a lengthy interruption in practice. The rationale for doing this “again,” or reinstituting the practice, is provided in the following verses.

Those who came out of Egypt had been circumcised, but all those who had been born during the wilderness period had not, as of yet, been circumcised. Those who had been circumcised had been part of the older generation that had walked out of Egypt, had crossed the Red Sea, and had received the covenant of God announced at Mount Sinai. The fact that the new generation was being circumcised did more than make them “look” like their predecessors. The circumcision of all males suggested that this new generation’s identity was rooted in the life of this covenant God. They were not “second class” citizens or replacements of a former generation; they were in fact the people of God being prepared to be full recipients of the covenantal blessings and full recipients of the “land flowing with milk and honey” that had been promised to their ancestors.

The act of circumcising itself takes on an added meaning in Joshua 5. At Gilgal, the LORD announces, “Today I have rolled away from you the disgrace of Egypt.” The familiar “today” of Deuteronomy is intoned again in Joshua. On this day, circumcision opens up a new future for the people; they are released from the disgrace of Egypt. Such disgrace is not a reference to slavery or oppression in Egypt, as some suggest, but clearly a reference to the disobedience of those who came up out of Egypt. The act of disobedience of the former generation that disqualified them from entry into the land is met in Joshua 5 with an act of obedience by the present generation, thereby releasing them from the disgrace of the older generation and signaling their preparation for Passover as well as entry into the land.

Verses 10-12 shift from circumcision and wanderings in Egypt to Passover and life in Canaan. As the circumcised people of God who have had the disgrace of Egypt rolled back, they are prepared to celebrate the feast of Passover. Just as the earlier generation had celebrated Passover on the fourteenth day in remembrance of their liberation from Egypt (Exodus 12:6), this new generation celebrated Passover on the fourteenth day, but the celebration appears connected now with the entry into the land as had been promised to their ancestors.

Surprisingly, however, the theme of Passover remains a minor theme in this brief section. The emphasis has shifted from Egypt to the land of Canaan (verse 12). On the day after Passover, they ate from “the produce of the land” (verse 11). Not only had the “disgrace of Egypt” been rolled back at Gilgal, but the scarcity of food had been replaced with a productive land that would satisfy the people. The new generation will no longer be a people of the wilderness forced to live off of divine provision, but now will be a people of the land ably supplied by their inheritance.

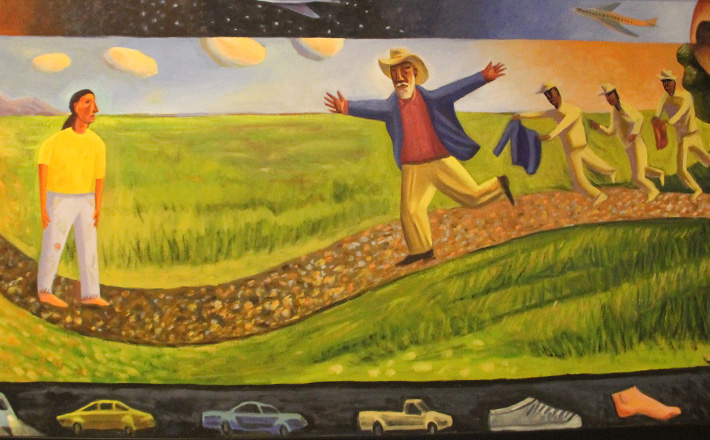

The connection between Joshua 5 and Luke 15 in the Lectionary is often questioned. Yet together they echo the words found in the reading from the Psalms: “Happy are those whose transgressions are forgiven” (32:1). In both Joshua 5 and Luke 15, the theme of wandering is paramount. The nation wanders in the wilderness, abounding in disobedience. The youngest son wanders in a different sort of wilderness, nevertheless, lost in disgrace. In both stories, the wanderers make their way back home out of the wilderness, but in both stories neither the nation nor the youngest son is able to shake the disgrace that has resulted from disobedience and wandering. It is only the pronouncement by the “other” (God in Joshua 5; the father in Luke 15) that redeems them from their past. “Today I have rolled away from you the disgrace of Egypt.” “This son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!” Each pronouncement is followed by a feast. In both cases, the feast symbolizes that the shame of wandering has been rolled back and replaced instead with the promise of a new “today.”

March 14, 2010