Commentary on Jeremiah 14:7-10, 19-22

It is hard to read Jeremiah in our contemporary context; it is such an alien text.

The passages in the lectionary this week are excerpts from a longer passage about a severe drought that rocked Judah. It must have been particularly devastating, because the beginning of the chapter assumes that the audience knows which drought this is. The weather patterns in the Levant were particularly unreliable, so periodic droughts were the order of the day, but Jeremiah 14:2-6 illustrate the scope of the drought: from city to the steppe.

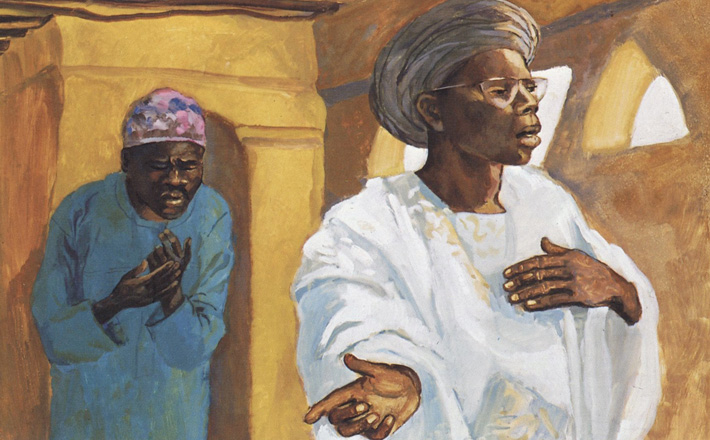

It is easy to dismiss this poem’s response to the drought as superstitious and naïve. The text interprets this natural disaster as God’s punishment of Judah for its sins. The people are depicted as pleading with God to forgive them. “We acknowledge our wickedness,” the poet cries. “Do not spurn us!” The audience should hear the community’s desperation.

The final two verses appeal to God’s ego, if you will. The speaker swears that they will not turn to other gods for relief from the rain. In 1 Kings 18, Elijah wins a contest against the prophets of the Canaanite storm god, Baal, during a similar catastrophic drought, proving to the witnessing audience Yahweh’s effectiveness as a more powerful storm god. Fresh water was the oil reserves of the ancient world. Their economy, based as it was on agriculture, ran on fresh water. Droughts of this magnitude reached into every corner of society: from rich landowners to poor workers, even to the farm animals, which were the ancient equivalent of tractors and plows.

The poet urges God to act “for your name’s sake” (Jeremiah 14:21). This phrase attests that what is at stake is not just economic security but cultural and religious stability. It is not only that other nations will mock the Judeans for worshipping a weak deity, but this weakened country would be vulnerable to foreign invasion, leading to colonization, as happens later in the book of Jeremiah when the Babylonians take over the land. Such colonization could be accompanied by forced recognition of the gods of the victors. This religious factor is highlighted in the reference to Zion in v. 19 and to God’s throne in v. 21: both references to the temple that stood in Jerusalem. If Jerusalem falls, the Yahweh’s own temple will be destroyed, the site where Yahweh’s “name” dwelled.

Of course, for those who know the book of the Jeremiah, this terrible prediction comes true. The nation is invaded, the city walls breached and the temple destroyed. As horrible as this natural drought is, the drought and famine that the city experienced during the long Babylonian siege was even more severe. Later in the book, after Jeremiah has been thrown into a pit as a false prophet, he is saved by an Ethiopian eunuch, Ebed-Melech, who understands the cruelty of death by starvation (chapter 38). Not only do Jeremiah’s warnings not change people’s behaviors, but he himself becomes the paradigmatic sufferer of a city in collapse.

So how do we read the text today, especially when we do not want to tell people who suffer from natural disasters that it is all their fault, that this is a punishment from God for their wickedness? For me, there are three things that I take from this text. The first is to listen, because the voices in Jeremiah 14 are the voices of people around the globe today who feel powerless in times of natural disaster. Their economies are so precarious, that small climate changes that are easily tolerated here can have devastating effects on families, villages, and even national economies.

Second, Jeremiah’s voice is that of an insider, part of the community that suffers. This is not the words of a dominant culture that is “othering” a colonized country by depicting them as evil. This is no Pat Robertson chastising an evil Haiti. In this particular poem the book tries to capture the communal voice of the people struggling with the question of where God is in times of communal tragedies that are beyond the people’s control. Although in Jeremiah 14:11, God tells Jeremiah not to intercede on behalf of this people, the text still manages to record the continuing cry of those who suffer.

Third, the poem acknowledges that humans have a role to play in communal disasters. And this is the text’s hardest message. No, we don’t control the weather, but how do the choices we make render some communities at such great risk during natural disasters? How did our national economy, for example, and our cultural assumptions, make the flooding in New Orleans even more devastating for the city’s poorest citizens? And who in our own community will be next? Can we dare to say, “We acknowledge our wickedness, O Lord?”

October 23, 2016