Commentary on 2 Samuel 11:26—12:10, 13-15

2 Samuel 12 is one of the most compelling stories of injustice uncovered.

The story actually starts in the last few verses of 2 Samuel 11:26-27 with Bathsheba crying bitterly when she heard about the death of her husband Urijah. But then life moves along at a brisk pace with David marrying the newly widowed Bathsheba and their son being born a couple of months later. Time passes and the last word about the injustice seems to have been spoken. Except the narrator notes in v 27 that God is furious about what David had done.

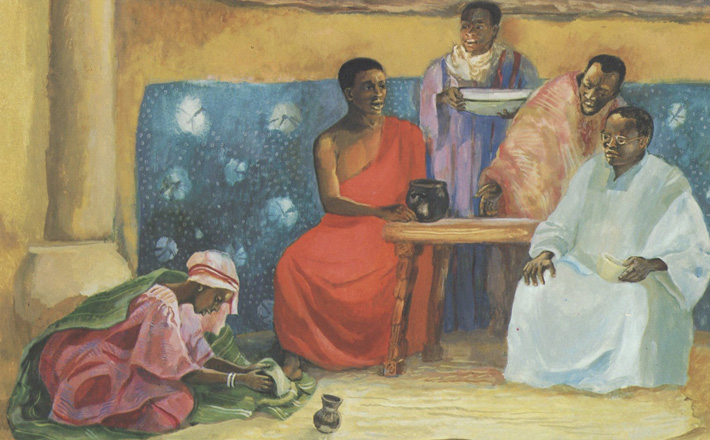

The next thing we as readers see in 2 Samuel 12:1 is the prophet Nathan arriving on David’s doorstep. It is uncertain how much time had passed since the end of the previous chapter, but it is evident that God’s displeasure with David resulted in God sending his prophet to go confront David. In one of the smartest tactics in order to get the King to admit what he had done, Nathan tells a story. He paints a compelling picture of a poor man who had a pet female lamb who he treated like a child, who slept in his bosom, and who ate from his plate, only to have a rich man who had many possessions and lifestock come by and take the little lamb in order to serve up a meal of roast lamb to his dinner guests. When David, displaying some hint of moral fibre, replies in outrage about this injustice, Nathan responds with the famous words: “You are the man!” In dramatic fashion, he thus uncovers the injustice that for many months and maybe even years had been covered up.

In terms of the biblical understanding of retribution, Nathan proclaims that the violence that David committed by means of the sword when he was responsible for the death of Urijah, will be returned upon him when the sword of his enemies will be against him. Indeed the saying is true: You live by the sword, you die by die sword. The story ends with David’s confession that he had sinned against God (2 Samuel 12:13) which has found poetic expression in Psalm 51 that is an extensive elaboration upon the terse admission of guilt in this narrative.

A number of perspectives are worth exploring in terms of this text. First, David’s confession is quite surprising. As Walter Brueggemann rightly points out, David who finds himself in a most powerful position could easily have silenced the voices of dissent around him — potentially even resorting to killing Nathan in order to make him shut up (1 & 2 Samuel, 282). After all, leaders today all too often insulate themselves from critical voices which conceivably create circumstances rich for injustice to germinate. The fact that David admits that he was wrong shows some sense of morality, even though admittedly his confession focuses on his sin against God with no mention of his actions killing Urijah and violating Bathsheba.

Second, Nathan emerges as an incredibly courageous prophet speaking truth to power and doing so in a quite clever fashion using imagination to draw the king into judging himself. Noteworthy is the fact that the language used for the rich man taking the lamb is the same language that was used in 2 Samuel 11:4 when David took Bathsheba. Moreover, the verb “to take” is the language that is used in 1 Samuel 8:11-19 by the prophet Samuel when he warns the people about the dangers of the royal office. Kings take whatever they want. In the context of leaders abusing their power, one truly needs whistle blowers and other upright individuals who stand up and say “No!” to injustice and the abuse of power.

Third, probably the most disturbing part of this narrative is that, after David’s confession, Nathan promises David that he will not die, however his son will. This troublesome aspect of this text reflects the biblical idea that the sins of the fathers will be visited upon the sons — literally in this case. But how is this fair? And was it perhaps the illness of the child that caused the people around David, including also Nathan, to ask the question: Why would this baby become sick and die? In terms of the theology of the day, the answer would of course be because of the atrocious things David had done.

It is very important though in a sermon to challenge this direct association between sin and suffering. The reason for this is that such religious views, even though forming a distinct part of this biblical text as well as many others, is deeply problematic when children today would get sick and die. In this regard, it is significant that, in the rest of 2 Samuel 12 that does not form part of the lectionary reading but nevertheless offers important perspective on this story, David is shown to fast and pray for the life of his child. It seems that through these religious rituals David is resisting the forces of death as well the underlying theological framework for the sake of the child. David’s actions calls to mind the mothers and fathers, teachers, health care professionals, and relief workers who work relentlessly to save children in a context of exceedingly high infant mortality worldwide.

Finally, glaringly absent from this text is Bathsheba’s voice. It is ironic that whereas she in the beginning of the pericope was lamenting for her husband, now when her child dies we do not hear what had to be this bereaved mother weeping at the top of voice. Perhaps Bathsheba’s silence in this text about the death of her child in addition to the events that led her to this place is fitting given the fact that so many victims of sexual violence today are silent and silenced. Ultimately it is up to the preacher to stand up as Nathan had done and uncover the ugly reality of violence against women as well the high incidence of infant mortality.

June 12, 2016