Commentary on Hebrews 5:5-10

This text from Hebrews is part of an exposition on the high priestly character of Jesus that begins at 4:14.

The subject is picked up again at the end of chapter six and is the focus of a discussion that runs through chapter ten. The motif is, finally, incorporated into the end of the Epistle (13:10-16) in a stunning description of the sacrifice Jesus offered “outside the camp” on behalf of all. The sacrifice of Jesus did not occur within the holiness of a temple, but in a place all considered profane — a Roman killing field. If one reads to the end of this highly sophisticated rhetorical document, Hebrews’ ironic use of the cultic language of “priest” and “sacrifice” becomes apparent. Such terms are simply emptied of their common-sense “religious” meanings; they are “deconstructed.” What is “holy” after the cross? What is “profane” when the place of Christ’s own offering is Golgotha? What is a “sacrifice” after the body (10:10) and blood (9:22) of Christ atones for Sin (10:18) once and for all (9:26)? What is priestly service when the Son of God now appears “in the presence of God on our behalf” (9:24)? Such are the questions that crowd upon one when engaged in a close reading of Hebrews’ narrative use of “cultic” language.

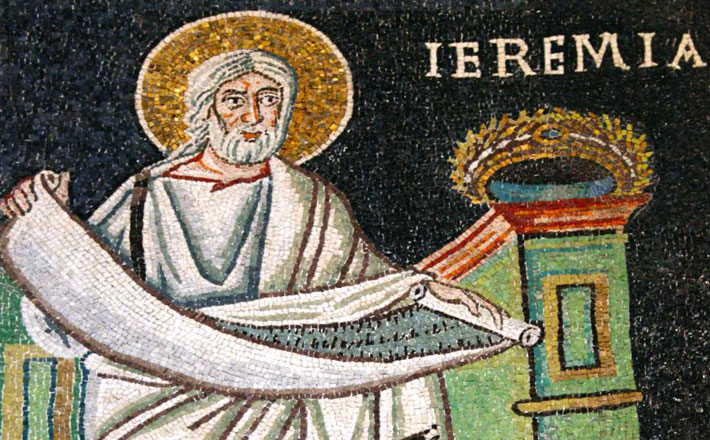

The text for today describes two very different aspects of Jesus. Hebrews 5:5-6 indicates Hebrews’ interest in the Old Testament foreshadowing of Jesus’ messianic roles. He is here understood both as “King” and “High Priest” by means of two Psalms addressed by God to the Son. Psalm 2:7 (“You are my Son, today I have begotten you”), earlier quoted at Psalm 1:5, is also found in the gospel accounts at the baptism of Jesus. In its Old Testament context, it is a Psalm that celebrates the enthronement of a king. Psalm 110:4 (“You are a priest forever, according to the order of Melchizedek”; see also Psalm 7:17), a text uniquely of interest to Hebrews in the NT, speaks of Jesus in terms of the mysterious Canaanite “priest of God Most High” (Genesis 14:18). In Hebrews, Jesus’ high priestly functions are understood in terms of Melchizedek and not that of the Levite order established by Aaron (Hebrews 7:11-14). Interestingly, Hebrews understands Melchizedek to be a figure of Jesus that foreshadows both roles of “King” and “Priest.” An etymology found in Hebrews 7:2 of melchi-zekek allows Hebrews to understand Jesus in royal terms: “His name, in the first place, means ‘king of righteousness’; next he is also king of Salem, that is, ‘king of peace.’”

If Hebrews 5:5-6 articulate Hebrews’ high Christology by means of the royal and high priestly attributes of Jesus, vv. 7-9 accentuate the vulnerability that is characteristic of his humanness during the “days of his flesh” (v. 7). Jesus suffers. Two issues present themselves in these verses. The first has to do with the nature of the prayer Jesus offered up and its response. The second concerns the notions of Jesus’ “obedience” and its connection with his movement towards “perfection.”

Today’s text appears two other times in the RCL. Hebrews 5:7-9 will reappear on Good Friday. A longer version (vv. 1-10) will come later this year in Proper 24. The choice of the text for the Fifth (and last) Sunday in Lent as well as on Good Friday is, no doubt, related to the way Hebrews speaks of Jesus’ prayer in v. 7: “He offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears.” One naturally conflates this expression with the gospel tradition of the Prayer at Gethsemane (Mark 14:32-42; Matthew 26:36-46; Luke 22:39-46; John 12:27). In all versions, Jesus prays for deliverance, but places himself under God’s will. So, for example, in Mark one finds: “Abba, Father, for you all things are possible; remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want.” Scholars point out, however, that the wording of Hebrews 5:7 displays an idiomatic expression of earnest Jewish prayer. That is, Hebrews might not intend to evoke the Gethsemane tradition, but simply describe Jesus’ prayer in general (i.e., it is pious).

If that is the case, the next two phrases are puzzling. Jesus prays “to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverent submission.” If the Gethsemane tradition is not alluded to here, the question is: “If Jesus prays for deliverance, and all things are possible with God, why is it that Jesus is crucified?” Verses 8-9 must supply the answer: “Although he was a Son, he learned obedience through what he suffered;and having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him.” Here Hebrews, I believe, is moving in the same theological territory that Paul explores in Romans 5. If the “obedience” of Christ is the answer, the problem is “disobedience” of human kind, epitomized by Adam. As Paul says in Romans 5:19, “For just as by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners, so by the one man’s obedience the many will be made righteous.” Hebrews, however, goes one step further. Such obedience to — or perhaps better, “trust” in — God, Jesus “learned through the things he suffered” (emathen … epathen). “Suffering,” seen in this light, is understood by Hebrews as that which is most characteristic of human life. To repair the breech Adam’s distrust opened up in the relationship between humanity and God, Jesus entered into the “suffering unto death” that resulted from Adam’s sin. The obedience to (or trust of) God, lost by Adam, had to relearned. Such learning, Hebrews suggests, Jesus won through the things he suffered.

“Perfection,” in Hebrews, then, was not simply given to JeKCRsus; nor is it a “moral” category. Jesus became “perfect” only because he continued to trust in the goodness and mercy of God while suffering the full power and depth of evil. This way of salvation fulfilled by Jesus had, however, been prepared by the Word of God. “In many and various ways” (Hebrews 1:1), God had previously spoken of God’s mercy. Scripture had revealed that God is the God of life and wellness. The heroes of the faith (Chapter 11) had exhibited elements of a faith that was “the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1). It was in this God of goodness and mercy revealed in Scripture that Jesus placed his faith, his “conviction of things not seen” (nor experienced), through his passion and even his death on the cross.

Here, in these few verses of today’s lesson, we encounter the remarkable juxtaposition of Hebrews “high” Christology of the preexistent Son with a witness to the vulnerability of the man Jesus, who suffered a difficult life and a painful death. These two elements of Hebrews’ Christology (divine/human) set side-by-side, remain in paradoxical tension. One thing, however, is certain. The vulnerability of Jesus “in the days of his flesh” reveals a gracious God. As Hebrews states: “Having been made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey [or trust] him, having been designated by God a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek.” With Jesus’ elevation to the right hand of God, the demand for blood sacrifice is extinguished, as is the need for humans to suffer to perfection. Liberated from such obligations we are freed through Christ to trust anew in the mercy of God.

Trust in a gracious God, then, lies at the very heart of the “obedience” God now demands of us. From the perspective of my own Lutheran theological tradition, this demand is encountered more often in the gift of “faith”. Such faith is understood neither as the belief in the existence of God (“even the demons [so] believe and shudder,” James 2:19) nor merely in intellectual assent to the church’s doctrine. Rather, “faith” is understood in terms of a continually tested belief in God’s goodness and mercy. Doubt, then, is the mirror image of faith. Doubt is not disbelief in the existence of God, but the suspicion that mercy is not to be found in God’s innermost heart.

March 22, 2015