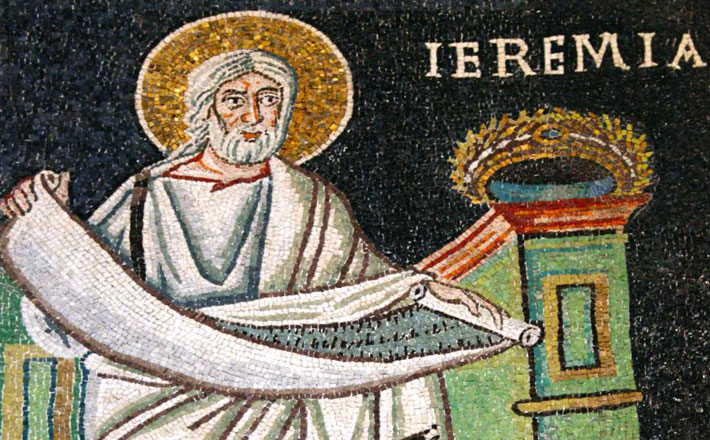

Commentary on Jeremiah 31:31-34

The images used in Jeremiah 31 are predominantly familial rather than political or military.

Female images, especially associated with birth and new life, are prominent. God is imaged as a loving, nurturing parent (both father and mother), comforting those who sorrow and caring for the needs of a bruised community.

This passage is picked up in several New Testament texts (e.g., Luke 22:20; 1 Corinthians 11:25; 2 Corinthians 3:5-14; Hebrews 8:8-12; 10:16-17) and has generated various interpretations, not always positive. Some have thought that the text, with its references to the law, fosters a kind of legalism. Others have interpreted it in supersessionist terms, with Christians becoming the sole people of the new covenant. Still others reject such interpretations and consider the text to be a theological high point.

It is important not to isolate this text from its context. The new covenant is to be accompanied by a repopulation of the land and a rebuilding of Jerusalem (Jeremiah 31:27-28, 38-40). The context is earthly, not heavenly. This covenant is given to Israel, not to some new people that God will create. Indeed, God will make a new covenant with all Israel, including Northern and Southern kingdoms. The promise is given to a dispirited people in exile. Unless the new covenant is God’s promise for this specific group of people, it is a promise for no one else. To interpret this text in individualistic, universalistic, or narrowly spiritual terms violates its context.

This is the only Old Testament passage where “new” modifies “covenant.” What is “new” about this covenant is disputed. This covenant is explicitly said not to be like the one that God made with Israel at Mt. Sinai (Jeremiah 16:14-16; 23:7-8). The new covenant is linked neither to Mt. Sinai nor to the exodus! The return from exile is a newly constitutive event for Israel and the new covenant is an accompaniment integral to that event. This covenant will be made by God “after those days” (Jeremiah 31:33), after Israel’s return from exile.

What this constitutive event entails for Israel was spelled out in Jeremiah 24:6-7; God will build and plant them and “give them a heart to know that I am the Lord” (see Jeremiah 32:39), replacing the “evil will/heart” so characteristic of Israel’s life before exile (see Jeremiah 13:10). The old covenant formula of relationship still applies, “I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (Jeremiah 31:33; 30:22; 31:1). But Israel will now be constituted as the people of God in a new way. God will give them a new heart so that they will know the Lord, indeed all the people will know the Lord. God will be their “husband” (ba’al, Jeremiah 31:32; recall Israel’s seeking other lovers among the Baals), evident in the phrase, “know me” (Jeremiah 31:34), but what that knowledge means for Israel will change (see Jeremiah 32:38-41).

The law remains a key point of continuity between old and new; but it will be written upon the heart, no longer a written Torah, and new in much of its content in order to fit the new living situation.

The repeated “for” in Jeremiah 31:34 gives two reasons why teaching will no longer be needed: they shall all know God and God will forgive their iniquity. That all will have a knowledge of the Lord and God will forgive are the center of this new covenant. Israel’s past becomes truly past; never again need they wonder whether God would remember their sins. Everyone, from whatever class or status, from priest to peasant, from king to commoner, from child to adult, will know the Lord.

A key question arises at this point. Inasmuch as the people broke the old covenant, what enabled the community to survive? When this breakdown occurred at Mt. Sinai, Moses appealed to God on the basis of the ancestral covenant (Exodus 32:13), an appeal that God honored. From this Mosaic intercession we learn that the Sinai covenant was not the event that constituted Israel as the people of God; they were God’s people from early in Exodus (Exodus 2:24; 6:2-8). The Sinai covenant was “under the umbrella” of the ancestral covenant. Hence, even though the people had “broken” the Sinai covenant, the ancestral covenant persisted so that Israel remained God’s elect and God’s promises continued to be a reality. God has made unconditional promises to this people independent of the covenant at Sinai.

Jeremiah nowhere refers explicitly to this ancestral “covenant,” but it is implicit in several texts. The heart of the promise in Jeremiah 33:13-26 refers to the offspring of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Given the connections between Abrahamic and Davidic covenants, it is notable that God considers the latter to be inviolable (33:14-26; see 23:5). The promises of God are grounded even more deeply in the covenant with Noah (33:14-26; see 31:35-37). God’s promises to Israel are as firm as God’s covenant with the entire creation.

Another link between the old covenant and new covenant is forgiveness. It was in the wake of the golden calf debacle that forgiveness emerged as a new reality for Israel. When Moses pleads for forgiveness, God responds with the making of a covenant (Jeremiah 34:9-10). Here forgiveness is made integral to the covenant. Similarly, God’s forgiveness is made the ground for the new covenant (31:34; “for”). God’s unilateral act of forgiveness for Israel (see Isaiah 43:25) is the basis upon which this new covenant is established.

This text also raises the question of fulfillment. Does the Epistle to the Hebrews present a supersessionist view? Though the word “obsolete” is used for the old covenant (Hebrews 8:13), Hebrews draws no negative conclusions regarding the relationship of the Jewish people to God. In fact, the promises to Abraham in Hebrews 6:13-20 are considered “unchangeable,” concerning which “it is impossible that God would prove false.” Hence, those who have been recipients of this Abrahamic promise remain the people of God, even though the Sinai covenant is broken or obsolete (so also Exodus 32:13). To those promises the faithful could cling.

Even from a Christian perspective this text has not been fully fulfilled. We still need to encourage others to “know the Lord.” And the claim that “all know me, from the least of them to the greatest” remains a promise for the future.

March 22, 2015