Commentary on Luke 18:9-14

This week’s text follows immediately on last week’s and is another parable about prayer.

Whereas last week’s offered a positive example in the character of the widow, this week’s is a study in contrast.

It begins with two comments about the addressees. Jesus tells this parable to some who (1) trust in themselves that they are righteous and (2) regard others with contempt. The first verb is used elsewhere in Luke at 11:22 with reference to the armor of the strong man, in which he trusts but which is taken away from him by the stronger man; to trust in one’s own righteousness is to rely on a flimsy defense.

The second verb, translated here regard with contempt, is used elsewhere in the gospels only at Luke 23:11 where Herod and his soldiers regard Jesus with contempt (translated there treat with contempt), and it is used again in Acts 4:11, again with Jesus as the one treated with contempt (there translated rejected). Already in the first verse the addressees have been established as deluded and those whom they treat with contempt have been identified with Jesus. And the parable will be a working out of this.

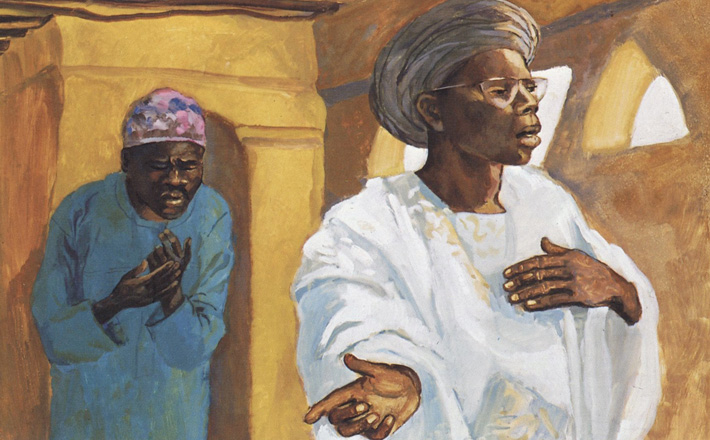

The parable begins with two men praying in the temple, and for that split second, we can have good hope for both of them, but as soon as they are introduced, the characterization of Pharisees and tax collectors in the narrative thus far comes into play, and we can be sure that the Pharisee of the parable will be standing in for the addressees.

Pharisees appear regularly in Luke. In 5:30, where they criticize Jesus for his association with tax collectors and sinners, they are associated with the righteous whom Jesus has not come to call. They reject God’s purpose for themselves by refusing to be baptized by John at 7:30, again in contrast with tax collectors.

In the next episode (7:36-50), Simon the Pharisee, by regarding with contempt the woman who anoints Jesus’ feet, establishes himself as the one who loves less! Notably, for the purposes of this text, they are grumbling about tax collectors again at 15:1-2, which elicits from Jesus the parables of the lost sheep, coin, and son, in which the Pharisees seem best suited to the role of the embittered elder brother.

Here the Pharisee is not embittered about the lost tax collector, but thankful not to be him. Perhaps the most significant and simplest thing we might observe about the prayer is that it is nothing like the one Jesus teaches his disciples to pray in 11:1-13. That prayer is entirely God-centric, opening with God’s name, kingdom, and will, then moving to our need of him for daily bread, forgiveness, and deliverance. This prayer is the prayer of one who has no need of anyone or anything because he is already in himself perfect, especially with respect to the wretched tax collector.

Tax collectors are associated with sinners throughout Luke, and the tax collector of the parable, a picture of shame, makes the association himself in a prayer of few words: “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!”

Just as tax collectors are hopeful characters in Luke (for example, 3:12; 5:27-30; 7:29-34; and especially 19:1-10), so are sinners. Simon Peter identifies himself as one (5:8); the woman who anoints Jesus’ feet is another (7:37). Sinners are often grouped with tax collectors as joint objects of the Pharisees’ grumbling and contempt. So we can feel sure that this man, like the sheep and the coin and the prodigal, is about to be saved by grace, as indeed he is.

He goes home justified, Jesus tells us. This verb has the same root as the adjective for righteous used in the first verse of the parable (18:9). The person who is justified is proclaimed righteous, so the use of the verb here echoes the use of the adjective in the introduction to the parable. The contrast between the Pharisee and the tax collector is between those who trust in themselves that they are righteous and those who trust in God to justify (or, we might say, to righteous) them. Jesus has already addressed the Pharisees using the same verb (16:15): “You are those who justify yourselves in the sight of others, but God knows your hearts; for what is prized by human beings is an abomination in the sight of God.”

The contrast between the one justified by God and the one who believes in his own righteousness as justification enough is summarized in the concluding statement: “ . . . for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and all who humble themselves will be exalted.” These two ideas have already appeared together in 1:52, where God is said to have lifted up (or exalted) the lowly (or humble). The phrase appears in full in 14:11 when Jesus is at dinner in the home of a Pharisee.

It all seems rather straightforward really. The addressees hear what we expect them to hear; the Pharisee and tax collector play their parts.

The challenge for us perhaps is to notice that we rather like being exalted. We might think of it as the satisfaction of a job well done or a duty fulfilled. And we might begin to believe that things we do (giving money to the church, doing religious or charitable activities, being upstanding members of society, making a well-deserved salary) or don’t do (being thieves, rogues, or adulterers) really might justify us, at least a little, might make us a bit better than those who fail where we succeed. But until we let go of that notion, the parable suggests, we will not go home justified. We will be prisoners to our own small righteousness. And we as a church will present a face to the world that does not invite it in.

On the other hand, we may need to challenge an assumption in ourselves that because of our failings, because we do not measure up to the standards of the Pharisee in ourselves, we are in some way secretly stained beyond redemption.

The strangely good news of the parable is that the role of the tax collector is available to all of us. We, and everyone around us, are all sinners and all beloved children of the gracious Father. The parable invites us to experience the freedom that comes with casting away our flimsy armor and throwing ourselves into the arms of God, who is already there, who has already found us, who wants more than anything to lift us up and lead us home.

October 27, 2013