Commentary on Psalm 32

Long before the insights from contemporary psychology concerning repression, biofeedback loops, and psychosomatic disorders, the ancient psalmist knew very clearly that unacknowledged and unresolved guilt could have serious physical consequences.

There is no reason to think that the language of Psalm 32:3-4 is purely metaphorical — “my body wasted away,” “groaning all day,” “my strength was dried up.” Unacknowledged and unresolved guilt was taking its toll. And it is still happening!

It is no wonder that some of the most penetrating analyses of sin and guilt have come in recent years not from biblical scholars and theologians, but rather from psychiatrists. For instance, Karl Menninger was motivated by his concern for mental health and a healthier society to ask Whatever Became of Sin? He was concerned that unacknowledged and unresolved guilt inevitably comes out in various forms of unhealthy “escapism, rationalization, and reaction or symptom formation.”[1]

Therefore, he called for a recovery of the concept of sin; and he suggested that clergypersons should take the lead: “It is their special prerogative to study sin — or whatever they call it — to identify it, to define it, to warn us about it, and to spur measures for combatting it and rectifying it.”[2]

The appearance of Psalm 32 in the lectionary offers a prime opportunity for clergypersons to take up the challenge “to study sin.” And almost certainly, it will be a challenge! As Menninger points out, sin-talk has not been and is not very popular. For one thing, it can sound archaic and overly judgmental. Then too, our concern for privacy and proper appearances makes confession of sin (or weakness or need) a bit risky.

As Gerald Wilson notes, “The cults of independence and perfection have prevented many a struggling evangelical Christian from admitting his or her fears, failures, and helplessness until the crisis was so great that it can no longer be denied and broke out with the utmost devastation for all those concerned.”[3] This reality, of course, underscores the importance of the challenge “to study sin.”

Perhaps the language of verses 3-4 suggests that the psalmist had arrived (or was about to arrive) at a devastating breaking point. If so, then she or he offers us a very important example of the benefits of confronting and confessing one’s sin. What ends up broken in Psalm 32 is neither the psalmist’s life nor the lives of those with whom the psalmist is concerned. Rather, what ends up broken is the psalmist’s silence!

While neither God nor the psalmists are in favor of sin, the real problem in Psalm 32 is not the psalmist’s sin but rather the psalmist’s failure to acknowledge and confess sin. It is crucial; therefore, that the silence be broken for, as James L. Mays points out, “the silence is the rejection of grace.”[4]

The tragic thing about the failure to confess sinfulness and need is that we close ourselves off from the liberating grace of God. A more literal translation of verse 5c emphasizes this liberating dimension: “you lifted the guilt of my sin.” A burden has been lifted! God bears the burden of sin with us or even for us!

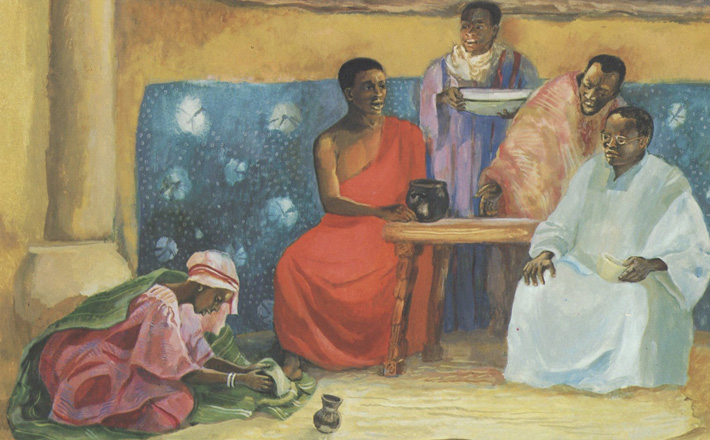

This, of course, is pure grace, anticipating both Jesus’ proclamation of the realm of God (see Luke 7:36-8:3) and Paul’s proclamation of the good news of justification by grace (see Romans 4:6-8 where Paul quotes Psalm 32:1-2).

To be sure, Psalm 32 is about sin and guilt; and it is rightly numbered among the Church’s seven Penitential Psalms (see Psalms 6, 38, 51, 102, 130, 143). But Psalm 32 is even more clearly about the divine willingness to forgive. This willingness is grounded in God’s essential character — that is, God is gracious, merciful, and steadfastly loving (see Exodus 34:6-7; and note “steadfast love” in Psalm 32:10).

Thus, it is appropriate that the tone of Psalm 32 is fundamentally celebratory. The opening double-beatitude establishes an overwhelmingly positive and joyful atmosphere for the entire psalm, and it is important to note that happiness here is all about being forgiven — it simply assumes we are going to sin!

As such, this double-beatitude serves to insure that the reader of the Psalms does not misunderstand Psalm 1:1-2, which has sometimes been interpreted to mean that happiness derives from keeping all the rules. But not so! Happiness begins with the reality of grace that invites humble reliance upon God and God’s willingness to forgive.

The celebratory character continues in the concluding section, after what turns out to be the turning point of the psalm in verse 5c. Not only does the vocabulary of sin disappear after verse 5c, but there are also explicit indications of faithful celebration — professions of trust in verses 7 and 10, along with joyful singing in verses 7 and 11.

NRSV’s “glad cries of deliverance” (verse 7) and “shout for joy” (verse 11) represent the same Hebrew root, which is often translated, “sing for joy.” In verse 7, the psalmist affirms that even God sings for joy, seemingly in response to the broken silence that leads to forgiveness (and perhaps anticipating the father’s joy in Luke 15 when the prodigal son breaks his silence, asking for, and receiving forgiveness).

Perhaps not coincidentally, the invitation to “rejoice” (verse 11) is repeated in Psalm 33:1, suggesting that Psalm 33 functions something like a continuing response to the good news of Psalm 32. Perhaps not coincidentally again, the keyword in Psalm 33 is “steadfast love “ (verses 5, 18, 22, recalling 32:10). Psalm 33 affirms “the earth is full of the steadfast love of the LORD” — verse 5). The poet of Psalm 32 seems to have known and acted upon precisely this good news.

So, amid the celebrations of verses 6-7 and 10-11, she or he offers us valuable instruction on the “way you should go” (verse 8). In short, the psalmist helps us “to study sin” by assuring us that in the presence of the steadfastly loving God, honest confession and liberating forgiveness are assuredly “the way . . . [we] should go” (verse 8).

June 16, 2013