Commentary on 2 Samuel 11:26—12:10, 13-15

The lectionary gives us only the terse conclusion to the lengthy and dramatic episode preceding Nathan’s parable.

Second Samuel 11:26-27 does provide a useful summary of the relevant events: Uriah dies, his wife mourns him, David marries Uriah’s wife when her mourning is over, and she gives birth to a son. Missing from this sliver of text, however, is any sense of controversy. After all, “the thing that David had done displeased the LORD, and the LORD sent Nathan to David” (11:27b-12:1a). What exactly is that “thing,” so ambiguously referenced, that David has done to displease God?

To answer that question, we must return to the preceding narrative in 2 Samuel 11. Preachers may want to remind their audiences of some of these details:

- David sees Bathsheba bathing from his rooftop and, after being told definitively that she is “the wife of Uriah the Hittite” (11:3), he sleeps with her anyway.

- Apart from verse 3, where the woman’s identity is reported to David, the narrative refers to Bathsheba only as “the wife of Uriah.” This rhetorical choice emphasizes David’s culpability as an adulterer, even as it serves to downplay Bathsheba’s own personhood.

- David tries to get Uriah to leave his battle post and sleep with Bathsheba in order to mask David’s paternity, should she become pregnant. Uriah, a pious and committed soldier, refuses to go down to his house, as abstaining from sexual intercourse was part of the ritual preparation for battle (see 1 Samuel 21:5). Even after David gets him drunk, Uriah still refuses to go down to his house to sleep with his wife.

- David finally instructs Joab to position Uriah at the front of the battle, where he is sure to be killed. David sends this message in the hand of Uriah himself.

Thus, “the thing that David had done” is not just one isolated incident, but rather a sequence of events that begins with his abduction of Bathsheba and includes a series of actions trying to cover up that death, ending in David’s conspiracy with Joab to arrange the death of Uriah.

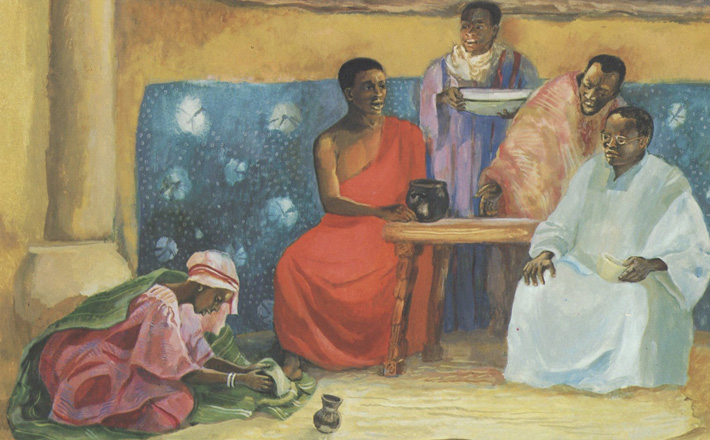

Like many effective homileticians, Nathan draws in his audience with a story. Inside the text, David is the only audience for Nathan’s parable, and David does not see his indictment coming. However, we the reading audience can begin to make connections right away: Uriah is the poor man, Bathsheba is his one little ewe lamb, and David is the rich man with a sense of entitlement. When Nathan cries dramatically, “You are the man,” equating David with the rich man in the story, David is the only one surprised.

Nevertheless, the parable helps us readers hone in further on “the thing that David had done.” The rich man is unwilling to take from his abundant flock in order to offer hospitality to a stranger, so he takes the one, beloved lamb from the poor man instead. David, flush with a sense of royal entitlement, has taken whatever he wants and then gone to great lengths to cover up his guilt. Prophetic condemnation reminds David, as well as us readers, that nothing can be hidden from God.

Earlier in the monarchic history, the prophet Samuel has already cautioned that kings are takers. When the people of Israel ask for a king at 1 Samuel 8, Samuel warns that the king will take and take and take (8:10-18). The prophet Elijah will later confront King Ahab for taking Naboth’s vineyard and arranging Naboth’s execution (1 Kings 21:1-29). In fact, the story of Naboth’s vineyard exhibits remarkable parallels with the account of David, Bathsheba, and Uriah.

In both instances the king (with much assistance from the queen, in Ahab’s case) interacts with a subject (Uriah or Naboth) shown to be far more pious than the king himself. When the king cannot get what he wants directly from the subject, he arranges for the man’s death through spurious means, then seizes what he wants from the man anyway. The tradition of prophets confronting kings about their exploitation of the ones they rule runs like a red thread through Samuel-Kings, and 2 Samuel 12 stands squarely in that tradition.

Reading this lectionary passage as condemnation of kings exploiting their power to take what does not belong to them inevitably raises the question of how we are to think about Bathsheba. In the world of the text, she may be as beloved as the poor man’s ewe lamb, but she is still property: a possession to be stolen. I would like Nathan to condemn the dehumanizing of Bathsheba, whom David abducts and sexually exploits. Yet no part of this lectionary passage or the narrative that precedes it worries about Bathsheba’s humanity in any obvious way. As mentioned above, the narrative almost exclusively refers to Bathsheba as “the wife of Uriah,” accentuating that David has done a wrong to Uriah above all else.

Though we should assume that, given David’s power, Bathsheba had no choice with regard to David’s advances, we nonetheless do not hear whether Bathsheba welcomed or rejected them; we know nothing of her opinion, of her state of mind, of the degree of her suffering. The narrative gives no voice to Bathsheba whatsoever, making it complicit in her dehumanization. Preachers should not shy away from acknowledging that the narrative itself exploits Bathsheba, because that point will certainly not be lost on many readers and hearers of this text.

After uttering the parable, Nathan names the abundance David has been given, the sins he has committed, and the consequences of his exploitative actions. The violence that David has enacted on his subjects will long be visited on his household. While verse 13 may perhaps be understood an expression of confession and absolution, the Hebrew verb translated as “put away” in the NRSV is better read as “caused to pass over” or “transferred.”1 The consequences of David’s actions will be borne most directly by his child, who will die, even though David will live. Rather than focusing on themes of sin and forgiveness, it may be best to find New Testament resonances for this text in Jesus’ admonishment of a disciple (identified as Simon Peter in John 18:10) at his arrest: “…for all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Matthew 26:52).

1The verb is a common one in Samuel with a consistent meaning of movement or relocation rather than disappearance or passing away: see A. G. Auld, I & II Samuel (Old Testament Library; Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2011), 467-468.

June 16, 2013