Commentary on Isaiah 9:1-4

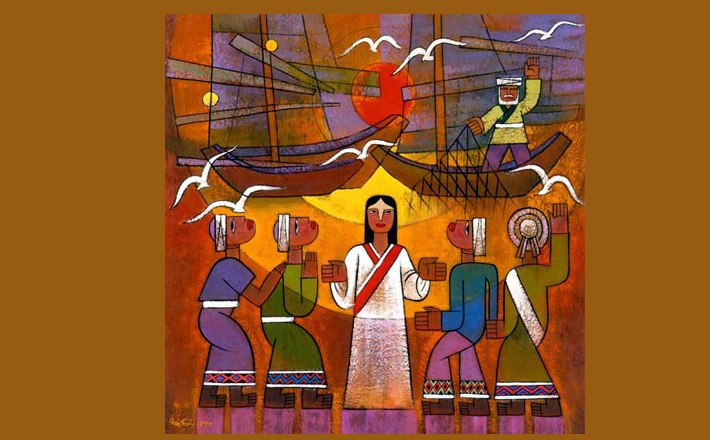

“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light.”

Central to the lectionary text for this week is the image of light shining in a context of deep darkness (verse 2). This image of light breaking through the darkness is a powerful means to capture both a sense of fear, hopelessness and anguish that is to be associated with not being able to see in the dark, and the hope, relief and deliverance that comes with the light being switched on — or in a world before electricity, the fire being kindled, the candle or oil lamp lit up. The joy and sense of relief that comes from light in the darkness is universal indeed — ask any toddler who is terrified of the dark.

For the people of Israel, this experience of light in the midst of darkness is not limited to one period of time. Isaiah 9:1-4 is a classic example of a prophetic text powerfully speaking to multiple interpretative contexts. In this regard the theme of “former time” in contrast to “latter time” is important (verse 1). Some scholars view this reference to the time of darkness and suffering in the time of Ahaz in contrast to a hopeful future that was expected in the time of Hezekiah. The source of the deep darkness at this time was likely the mighty Assyrian Empire who was known for their great cruelty and who eventually would destroy the Northern kingdom and terrorized the people of Jerusalem.

But this is true about empires then and now: Empires come, and empires go. So the “former time” and “latter time” can also refer for later readers of the book of Isaiah to the darkest of dark times under the Babylonian Empire who invaded Jerusalem three times, during the second of these attacks seeing the temple, the site of God’s home amongst the people, utterly destroyed. The light breaking into the darkness in this instance aligns with the hopeful visions of Deutero-Isaiah (Isaiah 40-55) that speak of a new dawn that is breaking, of the exiles that joyously will be lead home.

And for the New Testament writers, the “former time” and “latter time” would be understood in terms of the coming of the long expected Messiah. The Messiah who will come to break the yoke of the oppressor (verse 4), to bring liberation to those in bondage – the poor, the needy, the marginalized (Luke 4:18. Cf. also Isa 61:1), and who offers a radically different worldview in the context of the tremendous oppression experienced within the Roman Empire.

This promise of deliverance is indeed a source of great joy (verse 3) — joy that is likened to the jubilance of having successfully brought in the harvest so that the people have food to eat for the rest of the year, and in a more troubling image, the joy at dividing up the spoils of war. This latter image that assumes deliverance through victory in a time of war. This imagery is continued in the next verses that are more well-known and typically read in the time of Advent that speaks of “the boots of the tramping warriors and all the garments rolled in blood shall be burned as fuel for the fire (verse 5).” For this end of war will be signaled by the birth of the Prince of Peace, who is described as “Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father” (verse 6).

The hope for deliverance first in terms of the birth of a new Davidic king who will overturn Israel’s fortunes, which eventually evolved into the expectation of a messianic king that in a distant future will bring light to the world, are powerful images that have the ability to shape people’s minds and hearts. Very much breaking into a time of war, violence and imperial domination, these images capture people’s imagination, helping them to look up from their current circumstances and imagine that a world of peace and justice and an end to war, might just be possible.

Without imagination, without a vision of what life could and should be, people indeed might remain trapped in darkness. The prophet’s objective in providing his readers images of light while it is still dark, joy while people are still sorrowing, peace when the war is still raging is captured well in the oft quoted axiom of William Arthur Ward: “If you can imagine it, you can achieve it. If you can dream it, you can become it.”

Gene Tucker says something similar in his poignant commentary on this text when he considers the power of these texts to change “moods and feeling … to fuel the imagination” that may inspire people to try to change their external realities as well: “Such a day of peace and justice as envisioned in this text may never come, but it certainly will not if there is no image drawing people toward it”1

To preach on this text in the time of Epiphany in the beginning of a New Year is quite appropriate. The text’s ability to imagine a time of freedom, joy, light, and one could add love, friendship, and compassion in a time of darkness, in which everyone and everything shouts hatred, violence, war, and greed are vital for our survival as a people of God. Preachers are called to be proclaimers of such visions of light shining in darkness, of finding joy even in times of pain and sorrow, of enacting compassion and love in a context in which hatred and distrust reign supreme.

Preachers are called to bring to their congregants on this particular Sunday, as well as the rest of the year, the Good News of the Gospel evoked by this text. Their sermons will be doing something similar to the original sermon proclaimed by the Preacher-Prophet Isaiah, helping their communities in different times and places see the light breaking into whatever it is that has shrouded their world with darkness.

Notes:

1 Tucker, “Isaiah,” 124.

January 22, 2017