Commentary on Acts 2:1-21

Despite the theological attractiveness of seeing Pentecost as the reversal of Babel, there is little from the ancient historical and religious context to suggest that Luke or his audience would have made such a connection.

There is more evidence for linking the Pentecost event with the renewal of the Sinai covenant. The writer of Jubilees (2nd century b.c.e.) states that Moses is given the law at Sinai in the third month of the year (1:1) and later states that Pentecost (or Shebuot) is a festival observed the third month of the calendar (6:1), thus suggesting an implicit link between the giving of the law and Pentecost, an allusion that is made explicit by the time of rabbinic Judaism (b. Pesahim 68b).

Clues in Acts 2 suggest Luke stands in this stream of thought that moves from Jubilees to rabbinic Judaism. The sound, fire, and speech in the Pentecost narrative were phenomena associated with the Sinai theophany (Exodus 19:16–19), which itself suggests that Luke thinks of Pentecost in terms of a “new covenant” (Luke 22:20; cf. Jeremiah 31:31–34).

Exegetical Issues

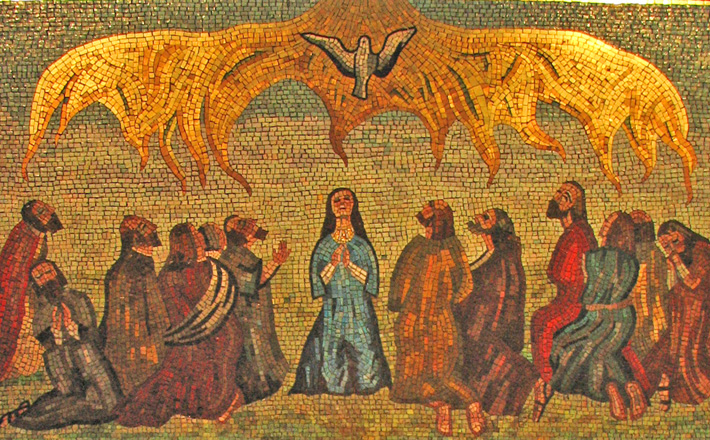

The coming of the Spirit is joined by two manifestations — “a noise from the sky, like a strong blowing wind(2:2) and divided tongues (that looked) like fire” (2:3). In describing the event as accompanied by these natural phenomena, Luke is echoing the theophany scenes of the OT, in which God’s presence is accompanied by similar signs (Exodus 19:16; Judges 5:4–5; cf. Psalms 18:7–15; 29:3–9).

In Acts 2:5, we read that “there were Jews living in Jerusalem, pious men from every nation under heaven.” In Acts 2:9–11, representative nations are listed. The list of nations in Acts 2:9–11 may be taken as an “up-date” of the Table-of-Nations tradition found in Genesis 10. The authorial audience has already been introduced to the Table-of-Nations tradition in Luke 10:1 in the so-called mission of the seventy, a mission that foreshadows the Gentile mission. So too echoes of the Table of Nations in Acts 2 symbolize mission of the Jerusalem church was a universal one.

Peter’s interpretation of the Pentecost experience is nearly three times longer than the narrative account detailing the event itself. This citation of Joel 3:1-5 in Acts 2:17-21functions as the bridge both to what precedes and follows it. The Joel prophecy serves as the authoritative interpretation of the Pentecost event.

This radical new community about which Joel speaks and which Peter says is realized in the earliest Christian community is remarkably inclusive. It is gender inclusive: “your sons” and “your daughters” (2:17); “servants — both male and female” (2:18). It is age inclusive: “your young people” and “your old people” (2:17). And if we are to take seriously the opening (“all people”) of this citation, then this community is also destined to be ethnically inclusive.

The Joel citation has been modified by the addition of several significant terms and phrases. That this new community itself is an eschatological sign is underscored by the change from “after these days” in the LXX text of Joel to “in the last days” found here in Acts. The Pentecost event is recast here as one of those wonders and signs (2:19) which will precede the coming of “the great and marvelous day of the Lord” (2:20).

Another element added to the Joel citations, “signs” (2:19) is perhaps the most significant addition and certainly strengthens the point made above. The phrase, “wonders and signs” or “signs and wonders” is a refrain throughout the first half of Acts. Of course, it first recurs in the context of this very speech in which Peter refers three verses later to Jesus performing signs and wonders (2:22).

But Jesus is not the only referent. Others who perform signs and wonders include: the apostles (cf. 4:30; 5:12). Stephen (6:8); Moses as (7:36); Philip (8:6, though note the absence of “wonders”); and Paul and Barnabas (14:3; see 15:12; 19:11). Signs and wonders, then, accompany the ministries of the leaders of God’s community in unbroken succession, from Moses to Jesus (who is a prophet like Moses, see 3:22), to the Twelve, to Stephen the Hellenist, to Paul and Barnabas, the leaders of the Gentile mission.

In making these connections, Luke seeks to demonstrate that the early church has been faithful to the traditions of Moses, despite criticisms otherwise (Acts 21:21). Membership in this radically inclusive community is available everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord will be saved” (2:21). The identity of this “Lord” is explored in the second part of this sermon (2:22-36), and the call to “be saved” is the focus of the invitation at the end (37-41).

Few, if any, biblical events have lent their name to describe a religious movement; yet, this is exactly the case for Pentecost. Pentecostalism was (and is) grounded on the belief, drawn from its interpretation of Acts 2, that speaking in tongues is the physical manifestation of a person’s having received the baptism of the Holy Spirit, an experience distinct from and subsequent to conversion that empowers believers for witness. Pentecostalism continues to be a major force in global Christianity, flourishing in all quarters and most denominations of the world.

Advocates of “cessationism” (such as B.B. Warfield) deny the ongoing effects of Pentecost, claiming that the “tongues” described in Acts 2 were not a permanent endowment but were rather limited to the apostolic period as a necessary sign for the inauguration of the church’s public ministry, not an event that was required nor even allowed in modern times.

How do we navigate among these various opinions? Did Luke understand the Pentecost event to be a “once-for-all” phenomenon? The answer here is simply “No.” Filling with the Holy Spirit occurs throughout Acts (cf. 4:31 et passim). Likewise, glossalalia is sometimes depicted as the public display of the gift of the Holy Spirit (cf. 10:46; 19:6).

On the other hand, it would be a mistake to suggest that tongues are a necessary evidence of baptism in the Holy Spirit (cf. 8:17) or that there is any clear sequence of baptism and reception of the Holy Spirit in Acts — sometimes baptism precedes reception of the Spirit (Acts 8:12-17); sometimes baptism follows reception of the Spirit (Acts 10:44-48); sometimes it accompanies baptism in the name of Jesus and the laying on of hands (Acts 19:5-6). All of this is to suggest that what is called for in our current context is a middle way that affirms the continuing reality of Pentecostal experience while correcting aspects of extreme expressions of Pentecostal theology. Christ’s ascension, then, is not a transport from one place to another, but a transition from one mode of existence to another.

Material adapted from The Acts of the Apostles. Paideia Commentary Series. Eds. Mikeal C. Parsons and Charles H. Talbert. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic (a division of Baker Publishing Group), 2008. Used by permission.

June 8, 2014