Commentary on Luke 2:[1-7] 8-20

The image of the angel appearing in the fields with all the glory to announce the birth of the Messiah stood out to me and stayed with me. The story brought great joy every time I heard it, but it also struck me as surprising. I would have expected such a grand announcement accompanied by all the pomp to occur in a royal palace far away from the fields.

Luke informs readers that the shepherds in the field were terrified when the angel appeared to them. The Greek phrase Luke uses literally means, “They were afraid with great fear.” It sounds somewhat redundant, but Luke is really driving home the point that the whole encounter was extremely terrifying to those shepherds. It is the unexpected and supernatural nature of the encounter that is especially unsettling to them. Surprisingly, the shepherds seem to get over their fear fairly quickly and decide to take a trip to Bethlehem to see the newborn child.

The angelic announcement contains key words such as “good news,” “savior,” and “Lord.” All of those were terms that were used and popularized by the Roman Empire. But there is a qualitative difference in how Luke employs them in this text. The good news in the context of the Roman Empire was meant almost always for the elite few, but the angelic announcement makes it clear that this good news would bring joy to all people.

The story of the angelic announcement comes immediately after Luke’s account of Augustus Caesar issuing a decree that census be taken. Everyone in the Roman Empire was required to participate in the census, but from an imperial point of view, only the elite few were entitled to joy, respect, and dignity. Within this political context, the promise of good news bringing joy to all the people is significant.

The shepherds are also told that the savior has been born to them. The dative preposition humin is translated as “to you” but, within the context, more accurately means “for you.” Soteyr, the Greek word for “savior,” was used by the Roman Empire to refer to the emperor. Whereas the soteyr of the Roman Empire, the emperor, consistently worked for those at the top, this soteyr was born for, and for the benefit of, shepherds and others like them.

The angelic announcement opens up the possibility of a very different reality for shepherds than what they had been subjected to. Could this really be true? Would such a reality actually materialize? They are about to travel to Bethlehem to find out. Impressively, the shepherds quickly move from a state of fear to an ability, or at least a willingness, to envision a different reality than their current situation, both for themselves and for others like them.

There are two key parts to the song that the heavenly host sings so spontaneously: “Glory to God in heaven” and “peace on earth to those on whom his favor rests.” The two parts are paralleled and placed right next to each other. There is significance to that placement. Coupling that promise about peace with glory to God suggests that the two aspects are interlinked. That is, God is glorified as much as there is peace on earth for those whom God favors.

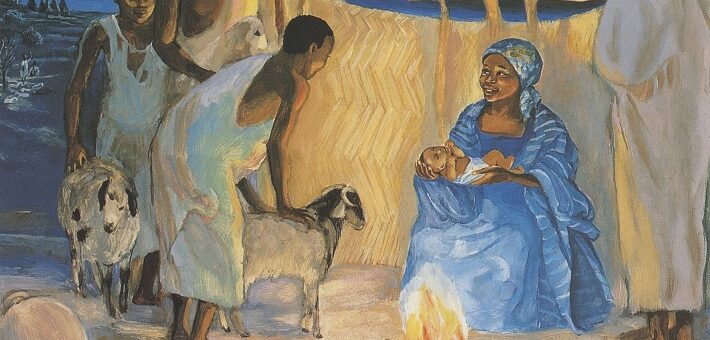

So far, in Luke’s narrative we have seen who the recipients of God’s favor are. It is people like Mary and the shepherds. We will notice again in subsequent Lukan sections, such as the Nazareth episode and the Beatitudes, that it is the powerless and the underprivileged who will receive God’s favor and peace.

The word “peace” was popular in the Roman imperial lexicon. Pax Romana (Roman peace) was about ensuring peace for those at the top, oftentimes by subjecting those at the margins to excessive violence. The Roman Empire did not see peace at the top and violence at the margins as paradoxical realities but as complementary components. That is, from their perspective, the only way to ensure peace at the top was by subjecting those at the margins to excessive violence. An extension of that approach and worldview is that it was acceptable to subject those at the bottom to unimaginable violence in order to ensure that those at the top could enjoy uninterrupted peace.

It is not too different from modern contexts where some individuals and communities are subjected to excessive violence on the pretext of ensuring that privileged communities can lead peaceful lives. But here is the angel, proclaiming peace precisely to those at the bottom of the Roman Empire.

Later in this section, Luke talks about how the shepherds glorified and praised God. Unlike the Roman emperor, who was keen to impress those at the top, this Lord will seek glory from those who did not seem to matter to those in power.

The shepherds made haste to visit the Christ child and celebrate his arrival. The Christ child whom the shepherds celebrated challenged the ethos and power of the empire that privileged a few at the expense of the many powerless. In this season of Advent and Christmas, we too eagerly anticipate and welcome the Christ child. We joyfully celebrate the Christ child who brought, and continues to bring, joy to all people.

Advent and Christmas are seasons of hope amid fear and despair. The arrival of new life in Christ imbues us with hope and reminds us that life triumphs in the midst of death and death-dealing structures of the empire.

But the child comes in many forms. And we are reminded in this holy season that every child, when nurtured with Christ-consciousness, can be empowered to dismantle the power of the empire. As we make careful preparations for the arrival of the Christ child and joyfully make many accommodations to our lives in order to welcome him, we are called to welcome all children with similar joy, eagerness, and anticipation.

December 25, 2023