Commentary on Isaiah 62:6-12

This Christmas, many Christians feel hopeless. Military violence, political strife, and environmental disasters have made life unbearable across the world. It’s difficult to sing “Joy to the World” in a time of global instability. Feigned cheerfulness won’t alleviate our anxieties about the future.

Isaiah 62 was likely written in the century after the return of Judean exiles to Jerusalem in 538 BCE, following its destruction by the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Although the homecoming was initially celebratory, life soon became precarious. The city was sparsely populated. The returnees faced harassment from surrounding peoples and suffered the degradations of Persian imperial rule.

Against this backdrop, Isaiah 62:6–12 offers a powerful word to our despairing world. It acknowledges its audience’s realities and responds with relentless—but hardly naïve—hope. That hope rests in the promise of a coming savior and the efforts of believers to rouse God to action.

Calling God to task

Isaiah 62:6 announces that “sentinels” will guard Jerusalem 24/7. The underlying promise is clear: the city is prepared for future attack. With the traumatic memory of invasion still fresh in the community’s mind, this oracle would’ve been deeply reassuring. But then the image shifts at the end of verse 6. The “sentinels” are “you who remind the LORD.” This command suggests that “sentinel” is a metaphor for a prophet (compare Ezekiel 3:17; 33:7), whose vocation included praying on behalf of others (Genesis 20:7; Jeremiah 27:18). The same metaphor appears in Isaiah 21:11–12, which inspired the Christmas hymn “Watchman, Tell Us of the Night.”

The speaker urges the sentinels to intercede continually on Jerusalem’s behalf. By denying themselves rest, they will disturb God’s rest with their prayers and move God to action (verse 7). In verse 1, the speaker likewise pledges not to “keep silent” or “rest” until Jerusalem is vindicated. A similar exhortation appears in Jesus’ parable in Luke 18:1–8, in which a persistent widow moves an unjust judge to action by constantly banging on his door.

When God is slow to fulfill divine promises, we shouldn’t be shy about pestering God. When we pray for our fractured and hurting world, we put God on notice that something’s gone horribly wrong. We expect better, but we know we can’t fix things by ourselves. The good news of this text is that such prayers can move God to action.

Economic inequality

In verses 8–9, God responds with a divine oath, thereby putting the divine reputation on the line. If justice doesn’t come, God’s “right hand” and “mighty arm” will be proven fraudulent. These verses promise that the audience’s enemies will no longer consume their agricultural commodities (contrast Deuteronomy 23:33; Isaiah 1:7). For nearly 300 years, Jerusalem had been paying tribute to Assyria, then Babylon, and now Persia. Judah was invaded three times during that period, resulting in the plunder or destruction of food stockpiles.

Such losses would’ve been devastating in a subsistence economy. If anything, agricultural losses were already the norm when the text was written. The fertility of the land likely hadn’t recovered from the Babylonian invasion a century earlier, especially if it included targeted attacks on the means of agricultural production (compare Judges 9:45; 2 Kings 3:19). Haggai 1:9–11 further suggests that returning exiles faced severe drought. Such environmental stressors exacerbated the economic stress caused by Persian tribute demands. These depravations hit the lowest economic classes the hardest—especially agricultural workers, whose produce was taken not only by foreign rulers, but also by wealthy domestic landowners (Isaiah 5:8; Amos 5:11–12; Micah 2:1–2).

In short, Isaiah 62:8–9 addresses the kinds of working-class resentments felt across the world today. There’s no more appropriate season than Christmas for Christians to denounce economic inequality as sinful. As Mary’s Magnificat reminds us, Christ’s coming portends radical economic redistribution (Luke 1:52–53). In God’s ideal society, laborers receive the most benefit from the goods they produce, not banks or shareholders or CEOs.

The coming savior

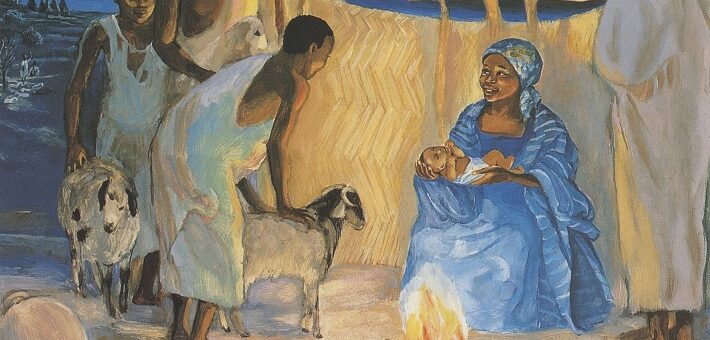

The climax of Isaiah 62 is verse 11: “Say to daughter Zion, ‘Look, your savior comes.’” The announcement of a coming savior resonates powerfully with the celebration of Christmas, and it’s appropriate for Christians to make that connection. At the same time, we must acknowledge the meaningfulness of this promise for its audience over 400 years before the birth of Christ. We should also make clear that this savior was expected to bring political as well spiritual liberation.

Verses 10–11 echo Isaiah 40:1–11, especially the claim that God’s “reward is with him and his recompense is before him” (40:11) and the command to “prepare the way” (40:3). In addition, the double imperatives in 62:10 recall the opening “comfort, comfort” in 40:1. Isaiah 40 was likely composed a century earlier than Isaiah 62, when Judean exiles first returned to Jerusalem. The repeated language in chapter 62 reaffirms those previous promises, despite the fact that they remained mostly unrealized.

Interestingly, verse 10 commands the audience to “prepare the way for the people,” not just for the coming savior. The image of a festal highway appears throughout Isaiah, and it is usually meant for returning exiles and global pilgrims (Isaiah 2:2; 11:16; 35:8; 66:20–21). When word gets out that the savior is coming, people will flock to Jerusalem. Rather than hoarding God’s promises for themselves, the audience must welcome refugees and seekers who want to be part of the new day that is dawning.

The repeated commands in verse 10 (“go … go,” “build … build”) create a sense of palpable urgency. Throughout Isaiah 62, the promise of redemption demands a response from the audience. Liberation is God’s work, but that doesn’t justify inaction on our part. We don’t just wait for the arc of the universe to bend toward justice; we disturb God’s peace until God brings justice. We don’t just sit around until the savior comes; we get the world ready for its deliverer.

December 25, 2024