Commentary on Matthew 26:17-30

The Lord’s Table is the founding practice from which the church grew.

Before there was church, there was table, where sinners and saints, disciples and outcast, believers and betrayers gather to remember, to anticipate what is still to come, and to embody together the restoring and unifying power of God. The Lord’s Table is living theater, the communal enactment of unity amidst diversity, rooted in who God is and demonstrating where humankind and creation are headed.

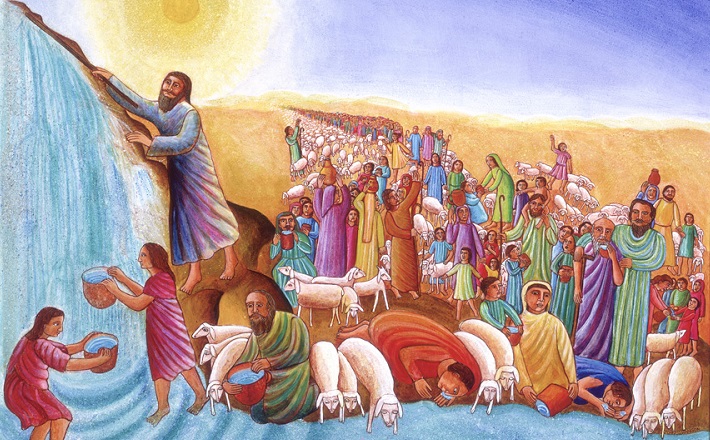

Because this is the definitive story of the church’s foundational practice, it reaches both forward and backward, into both the story of Israel and that of Jesus. Covenant is renewed even as it is about to be broken again. Betrayal, judgment, and the breaking of Jesus’ community intertwine with promise, forgiveness, and hope. Even the bread and cup are multivalent symbols that convey both judgment and redemption. The unleavened bread of Passover recalls Israel’s deliverance from Egyptian slavery, the bread of daily fellowship, and the abundance of the messianic banquet, already demonstrated in Jesus’ feeding of crowds in the wilderness (14:13-21, 15:32-38). It also anticipates the breaking of both Jesus’ body and the community of his followers.

Jesus’ identification of the cup as his “blood of the covenant” echoes Exodus 24:1-8, where Israel receives the Law and the promise of land, as well as the blood that protected Israel during the plagues in Egypt. The earliest canonical reference to blood, however, is in story of Cain’s murder of Abel, where the earth swallows Abel’s blood, which then cries out to God. The covenant of blood that Jesus establishes now with his disciples is the antidote to the curse of violence that the generation of Cain has carried throughout our long history of retribution, murder, and war (see Exodus 23:29-36). As Jesus makes covenant even with his betrayers, he makes brothers again of those who live in thrall of violence and death.

Even as his community splinters, Jesus anticipates and prepares them for that rupture, demonstrating the reconciling character of the divine power he embodies. Although Jesus shares the Last Supper itself only with the twelve (Matthew 26:20), here, too, Jesus signals his embrace of a diverse community that includes those who will desert and betray him — not only Judas, but the whole group of Jesus’ closest followers.

The betrayals begin already with the disciples’ chorus of denials, after Jesus announces that one of them is a betrayer: “Surely not I, Lord,” each affirms in turn (Matthew 26:22). We have seen denials like this earlier in the Gospel. Peter’s confession that Jesus is Messiah and Son of God turns quickly to denial when he rebukes Jesus for speaking of the cross that awaits him in fulfillment of his messianic calling (16:22). Just after the Last Supper, Peter again will assert his singular righteousness and deny Jesus’ prediction that he and the others will desert him (26:33-35).

These denials echo the speeches Jesus attributes to the scribes and Pharisees at the conclusion of his blistering critique in Matthew 23. They build memorials and decorate graves, he says, and deny that they would have participated, as their ancestors did, in the murder of the prophets (23:29-33). But Jesus says that this very denial makes clear that they remain in league with their ancestors, still full members of the generation of Cain (23:34-36).

We hear the same denials today, from both the political right and the left. In each case, denial, even based on the best of intentions, distances the denier not only from the action they will in fact pursue, but from the rest of humankind. The denier seeks to claim a place of exclusivity among the righteous or the truly enlightened, thereby building a wall between themselves and the other. In doing so, we fail to recognize that righteousness and justice rest upon the recognition our common humanity before God.

As each disciple utters his demurral at the Last Supper, culminating with Judas (26:25), each stands apart from the others. Their fellowship is fragmenting, even at the table where they remember God’s deliverance and covenant making with their ancestors. They are united in their spirit of denial, but the result will be their isolation and alienation. As they break bread with Jesus, their relationships with him and with one another are also breaking. The story of the Lord’s Supper thus subverts the assumptions that have brought the disciples this far on their journey with Jesus — our assumptions, too: that this meal is for insiders, for the righteous, for the chosen few who will judge the twelve tribes, for the true believers, the exceptions to Israel’s longstanding betrayal of God’s prophets.

In this mingling of fellowship and betrayal, we glimpse a central, albeit often overlooked dimension of Matthew’s story: in this Gospel there are, aside from Jesus himself, no heroes, no saints, no righteous privilege, and neither ethnic nor class insiders. Here at the Last Supper, there is only a body of broken and breaking people in the presence of the redeeming, reconciling Lord. They are with Jesus at table not because of their personal merits or righteousness, but as the preeminent representatives of Jesus’ reconciling work for both humanity and the whole creation.

While many commentaries argue, especially in treatments of the parable of the tenant farmers (21:33-46), that Matthew’s Gospel describes the replacement of the people of Israel by the Gentile the church, there is, in fact, no group — whether Judean, Galilean, or Gentile, women or men, Pharisee or disciple — that stands before God as worthy of the kingdom. Matthew’s story is not about the replacement of one ethnic, social, or political group by another. It is, rather, about who will “produce the fruit” of God’s reign — forgiveness and reconciliation — in its time.

By breaking bread even with his betrayers, Jesus is laying a foundation of mercy and reconciliation that will enable their restoration. It is only their recognition of their brokenness — remembered at table — that will make them fit agents of reconciliation after his crucifixion.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

God of promise, you made a covenant with your people in Israel, which you renewed at Jesus’ last supper. Renew your covenant with us daily, so that we might learn to live in your light and peace. We pray these things in the name of Jesus Christ, our Savior and Lord. Amen.

HYMNS

My song is love unknown ELW 343, H82 458, NCH 222

Go to dark Gethsemane ELW 347, H82 171, UMH 290, NCH 219

For the bread which you have broken ELW 494, H82 340, 341, UMH 615

CHORAL

Ave verum, Richard Robert Rossi

April 18, 2019