Commentary on Mark 11:1-11; [14:3-9]

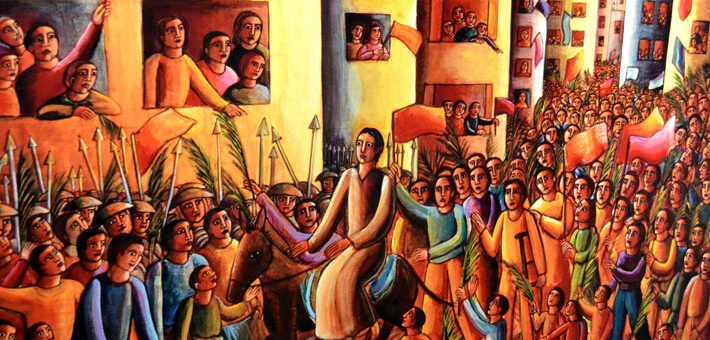

This week marks Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. He enters the city as it is preparing for Passover, which he has predicted will lead to his condemnation and death. The disciples, like us, cannot truly prepare themselves for the events this week will hold: from “Hosanna” to “Crucify” to “Alleluia,” the movements of the week are hard to prepare for.

Setting the scene: Passover in the first century

Passover marks the remembrance of the exodus from Egypt and a significant identity marker for the Jewish people. The calls to care for the poor and disenfranchised in the Old Testament often bear the rationale of the Lord’s deliverance of the people from Egypt.1 The celebrants of Passover gather to mark the deliverance God has already brought to the people of Israel by freeing them from enslavement. The Lord is already known as the one who delivers and the one who saves.

The Mount of Olives, from which Jesus begins his journey to Jerusalem, was associated with eschatological expectations. Zechariah 14 anticipates nations gathering in Jerusalem for battle and the Lord leading the battle (verse 3). Though in the historical context of Zechariah’s words, they relate to the rebuilding of the temple and to hopes for a renewed Israel, eschatological and messianic expectations were fairly prominent in the first centuries BCE and CE.2

Jerusalem was likely already preparing for the Passover observants to outnumber the residents of the city.3 Josephus indicates, “It is their custom to slaughter a greater number of sacrifices at this festival than at any other, and an innumerable multitude of people come down from the country and even from abroad to worship God.”4

The city needed to prepare for increased sacrifices in the temple, more people to feed, and the need for places to stay. One can almost imagine the smell of unleavened bread wafting through the streets and the unmistakable barbecue-y scent from the temple sacrifices overtaking the city.

One can also imagine bumping into people as the streets swell with crowds, not being able to see what exactly is going on, not being able to understand all the languages spoken, the orders of the Roman soldiers who are patrolling the streets (who were likely brought into town from elsewhere for increased security measures), and the energy of the celebration. Amidst this joy, energy, and likely frustration and confusion, Jesus rides a colt into Jerusalem and is celebrated with shouts of “Hosanna.”

Entering Jerusalem

So often, we read the Bible as if everything is by necessity and design. Most of us do not expect to laugh, nor to be delighted. But this scene is hilarious! Jesus instructs his disciples to steal a colt. It may be effective to cast the story in modern terms to gain a sense of what is happening: “Go into the city, and you will find there a car with the keys in the ignition. Bring it here. If anyone questions you, tell them ‘The Lord needs it, and we’ll bring it back right away, we promise.’”

The text would lead us to believe that the disciples calmly walked up, untied the colt, and returned to Jesus, who successfully mounted and rode the colt. Craig Keener explores some of the practical aspects of the disciples successfully cajoling the colt and Jesus riding it:

Donkeys sniff humans to distinguish friends from strangers, but the disciples that Jesus sends for the colt (Mark 11:1–2, 7) are undoubtedly strangers. … Bringing the colt to Jesus could thus pose an initial challenge. Even a young horse may react to a new potential rider by fleeing or seeking to protect himself.5

Perhaps, as Keener suggests, this colt cues into Jesus’ identity and is divinely inspired to comply.6 There is, however, room for faithful imagination here. How did the disciples who stole the colt tell the story to the others? What would the disciples have done if the donkey balked on the path? Did the donkey balk on the path? Jesus here bends the expectations of the normal, and in this bending of our expectations, there is humor and joy.

Jesus riding a colt into Jerusalem may mark another reference to Zechariah (9:9), which celebrates the coming king entering Jerusalem on the colt of a donkey. Again, it is important to bear in mind that Zechariah’s words refer to their own historical context but that, as with other prophetic texts employed by the Gospels, the Gospel authors reinterpret and reframe these texts in the light of Jesus. The crowds respond as if they understand the allusion with shouts of “Hosanna” and celebration, quoting Psalm 118:26.7

It is unclear who these crowds are and what, exactly, they believe about Jesus. Are they ones who have followed him throughout his travels? Are they pilgrims visiting the city from afar? Do they think Jesus is the coming king? If so, what gives them that impression? He has yet to teach, preach, or heal anyone in Jerusalem. And if this crowd believes that Jesus is the coming king, how do these shouts of “Hosanna” and blessing give way to “Crucify” and condemnation?

This week, many of us will gather with pilgrims in our congregations. Some of them might be regular attendees and some of them may come from farther afield. Today, we are all drawn into the celebration and the anticipation of the coming king and of God’s deliverance. Even today, we wait for God’s deliverance and look for God’s coming reign. Jesus may not be the savior we expect—nobody expected a Messiah on a cross—but he is the Savior we need, who walks with us through our joyous shouts of celebration, our deepest losses, and our greatest hopes.

Notes

- Exodus 13:3, 22:20; Deuteronomy 5:15; 6:12; 16:12; 24:18. This event is also a significant identity marker for the Lord (Exodus 20:2; Deuteronomy 5:6)

- “The War Scroll,” Frontline, accessed February 16, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/

shows/religion/portrait/scrolltranslation.html. It is, however, important to note that the expectations we find in the Dead Sea Scrolls relate a diversity of expectations for the Messiah and relate more than one messianic figure, including a prophet like Moses, a priestly messiah, a kingly messiah, and a warrior messiah. None of these expectations included crucifixion of an accused Roman criminal. - Population estimates for first-century Jerusalem vary widely, with minimalists claiming around 20,000 individuals and Tacitus estimating the population at 600,000 (Tacitus, Historiae 5.13).

- The Antiquities of the Jews 17.213. See also History of the Jewish War 2.3.10.

- Craig S. Keener, “The Unridden Donkey Colt: Mark 11:2 in Light of Equine Development and Pedagogy,” BTB 31, no. 1 (2022): 32.

- Keener, “The Unridden Donkey Colt,” 37–38.

- This psalm is part of a collection of psalms read at Passover celebrations (Psalms 113–118).

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Hosanna! King of all, you reign over all. Reign in our lives, triumph over evil, and teach us to follow in your footsteps. Amen.

HYMNS

All glory, laud, and honor ELW 344, GG 196, H82 154/155, UMH 280, NCH 216/217

Your will be done (Mayenziwe) ELW 741, TFF 243

CHORAL

Hosanna, Randall Thompson

March 24, 2024