Commentary on Ezra 1:1-4; 3:1-4, 10-13

When Cyrus II conquered Babylon, exile had become a multigenerational reality for the colonized Judeans. Perhaps for the first-generation exiles, the currency of the prophetic promises of Jeremiah (51:11) and Second Isaiah (44:28; 45:1) had waned, leaving despair to set in, whereas for the Judeans born into exile, it was likely easier to believe the empire’s religious ideology that the God of their ancestors had long been conquered.

Though Ezra’s claim of a fulfilled prophetic promise may enrapture us, we must not overlook what had changed for the colonized Judeans. For since the early sixth century BCE, their ancestral settlements were devastated by an avaricious empire and their kindred brutally sent into a life of captivity. The horrors of these events are unceasingly captured in the book of Lamentations. As the first-person subject expressed in Lamentations 3:19 after the fall of Jerusalem, “The thought of my affliction and my homelessness is wormwood and gall!”

For the Judeans thrust into exile by a violent empire, life in Babylon would have forever changed the way they saw the world, their history, and their faith. Without fail, the patriarchal social system that had afforded some of the Judean exiles their elite status in Jerusalem was severely disrupted by a new hierarchical system of imperial rule. Thus, it would be careless of us to assume that their elite status was pristinely transferred to Babylon, for their colonization inevitably reset their status in the world. In short, they were the conquered people.

Their demoted status is also reflected in the “yoke” metaphor that Jeremiah and Second Isaiah use to describe exilic life in Babylon (in other words Jeremiah 28:2, 4; 30:8; Isaiah 47:6). Indeed, such a subaltern status would partly explain why the coming of Cyrus as God’s anointed liberator made it into prophetic discourse. Arguably, it correlated to a strong desire for freedom among many of the colonized Judeans. In this way, their captivity was not simply the cause of generational traumas but kindled a spirit of prophetic resistance that resonated with many Judeans’ longings for freedom. As Jeremiah cried out, “Flee from Babylon! Run for your lives!” (51:6).

To counter their bounded state, the exilic prophets called the Judean exiles to exercise a trans-territorial mode of envisioning their physical and spiritual lives. A way of seeing the world that went beyond the most dominant constraining force ever manufactured by humans, the imperial impulse. For this reason, exile can be better understood not only as a subjugated position but also as a state of in-betweenness, which is where this week’s passage begins.

The in-betweenness of faith

In Ezra 1:1–4, the author sets our imagination in between the present and the past, in between exile and liberation, in between promise and fulfillment, and lastly, in between empires. Even God is presented in a state of in-betweenness, with Israel in exile and yet also “in Jerusalem” (1:3). This reading position provides a variety of benefits to our ways of seeing the world. Rather than be constricted by the boundaries of one fixed position, Ezra invites us into a creative in-betweenness in which the rulers of empires, faith, and prophetic promises intersect to produce a healing vision of liberation from empire.

At issue here is not whether the God of Israel actually “stirred the spirit of King Cyrus of Persia” (verse 1), for as reflected in the Cyrus Cylinder, the imperial archive attributed his liberating campaign to Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon. By putting the Judean exiles at the center of Cyrus’ edict, Ezra rendered seen what had long been marginalized within the imperial archive. As such, this passage invites us to unbind our imaginations and not to see the contradictions in the historical record but to embrace a vision of faith that subverts, counters, and resists the imperial archive.

Here, we need to suspend our nationalist ways of thinking and take up an imaginative in-betweenness that has us believe in an activist God who moves rulers to enact a generous policy of liberation and religious freedom for colonized people. Such a move reflects a life-giving strategy for how to care for colonized people, giving them a sense of agency by privileging their side of the story. Moreover, Ezra’s history-making functions as a strategy of care for colonized people because it begins with the lived experiences of “all survivors” (verse 4).

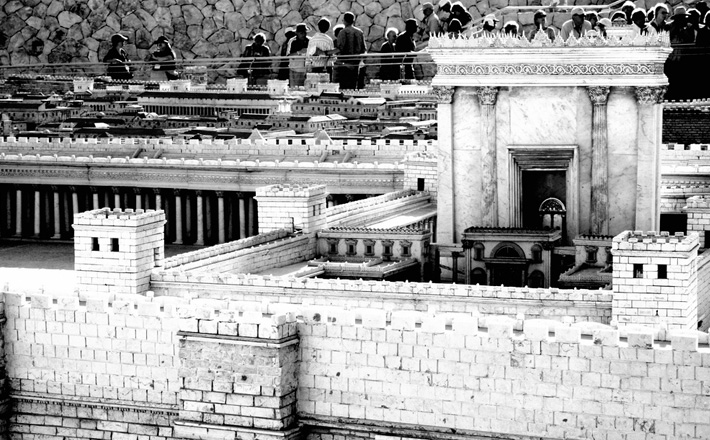

The imperial policy to rebuild the house of the Lord in Jerusalem points to a material lack that life in exile had imposed upon the Judeans. The list of materials needed to rebuild the temple—silver, gold, goods, and animals—suggests an inability of “all survivors” to accumulate wealth in exile. Ultimately, this survivor’s perspective admits to a lived experience of struggle, hardship, and daily toil, thereby acknowledging the full personhood of the colonized person.

The healing power of settledness

Where there are material needs, we can also infer the presence of mental health needs for colonized people. Hence, rebuilding the house of the Lord had in view a longing for the spiritual and physical settledness of the returning Judeans. Such a building project would reverse the empire’s religious ideology of a conquered God of Israel. Although settled in Jerusalem in a fixed sacred space, God’s house would serve as an emblem of the imaginative in-betweenness that came with life in exile.

For as the edict declared, God’s other abode is heaven—that is, to be at God’s house in Jerusalem meant placing worshipers at the threshold of heaven. Perhaps it was this in-betweenness—between heaven and earth—that inspired the multigenerational group of worshipers to sing a song in which “the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping” (Ezra 3:12–13). This was not a clashing chorus but a harmonious song of in-betweenness, where both lyrics of lament and celebration intertwine to heal the colonized mind and bring unbounded ways of seeing the world.

In the end, the returning Judeans could never erase their lived experiences in exile, for they represent deep wounds. And yet, their postcolonial wounds also did not eliminate their agency to create a new world.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

God of restoration, you brought your people home from exile and in their joy they rebuilt your temple. Deliver us from our personal and communal exiles, and help us to build up your church. Amen.

HYMNS

From heaven above ELW 268, GG111, H82 80, NCH 130

Awake, O sleeper, rise from death ELW 452, H82 547, UMH 551

God Is Here ELW 526, GG 409, NCH 70, UMH 660

Welcome Table ACS 969, GG 770, TFF 263

CHORAL

Lift up your heads, O ye gates, William Mathias

December 17, 2023