Commentary on John 2:13-25

Most of us are familiar with the story of the Cleansing of the Temple, when Jesus in righteous, prophetic anger cleanses the temple court of all the abuses going on within it, particularly the trade in animals for sacrifice. We find this story in all the Gospels, but John’s version is unique (see also Mark 11:15-18; Matthew 21:12-16; Luke 19:45-46).

In the first place, the story is located near the beginning of Jesus’ ministry in John’s Gospel rather than at the end, as in the Synoptic Gospels. There, it is one of the preludes to the Passion narrative, causing great offense to the religious authorities who know that Jesus’ wrath is directed at them and their abuse of power. Along with his teaching, this incident convinces them that he must die.

But not so in John’s Gospel. The cleansing story is part of the Cana-to-Cana cycle (2:1-4:54) where we find different reactions to Jesus’ ministry. This time it is the religious authorities in Jerusalem who react negatively to his actions.

It would be easy to become bogged down in historical questions about whether the cleansing of the temple happened at the beginning or the end of Jesus’ ministry or whether he did it once or twice. That is to miss the point. John’s Gospel works on its own understanding of time that does not necessarily correspond to a more wooden, chronological perspective. John puts the story there at the beginning because that’s where he needs it: to demonstrate the reactions of the authorities from the very start of Jesus’ ministry and, more importantly, to say something crucial about Jesus’ identity.

At first the story proceeds in a similar way to the Synoptic accounts. Jesus drives out the merchants from the temple court with their animals (2:14-15) in a passionate objection to their turning the house of God into a “market-place” (2:16). Animals were needed for sacrifice in the temple, but their incursion into the temple precinct itself during major festivals, along with the reputation for extortionate charges by the priests, made it a matter of deep moral and spiritual concern for Jesus.

But note the Johannine touch here: it is “my Father’s house” which Jesus is protecting. The phrase “my Father” is used on the lips of the Johannine Jesus about twenty-five times throughout the Gospel. It signifies his singular identity and authority as the divine Son and his unique affiliation to God as Father. It is this distinctive relationship which gives Jesus the authority to act as he does.

Another Johannine feature is the hastily constructed whip Jesus makes: not to lash the merchants with (as you might assume from some paintings of the scene) but rather, as the Greek makes plain, to drive out the sheep and cattle (2:15). Given that the animals are available for sacrifice, this action may even give the animals a chance of escape!

Note that, while Jesus certainly overturns the money tables, he commits no act of violence against any human body nor does he harm the doves whose cages are not overturned (2:15-16). This is a symbolic act of protest, not of violence; paradoxically, it is committed by the one who is the Lamb of God: the one whose sacrificial death will bring to an end all animal sacrifice.

Yet that is only half of John’s story. So far it has gone in a similar, though not identical, direction to the Synoptic versions (of which presumably our evangelist is aware). Now it takes a uniquely Johannine turn. In the second part (2:18-21) the temple now becomes a symbol of Jesus himself. In dialogue with the authorities, Jesus reveals that the destruction and rebuilding of the temple is itself a metaphor for his death and resurrection: “he was speaking of the temple of his body” (2:21).

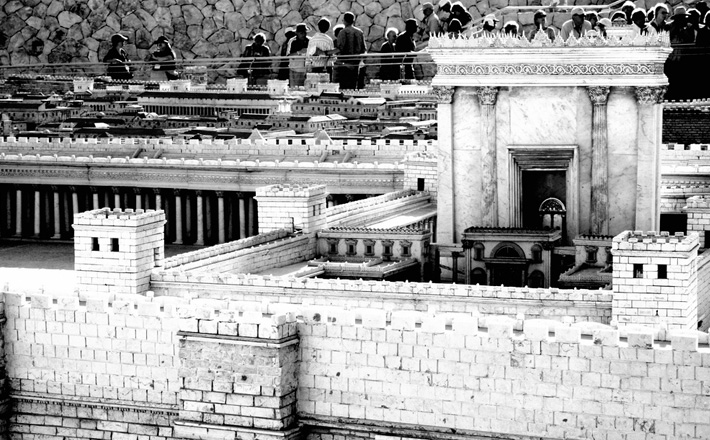

Jewish people were familiar with the destruction and rebuilding of the temple. The original temple was destroyed in 586 BCE by the Babylonians and was rebuilt after the exile. It was extensively renovated several centuries later by Herod the Great. In 70 CE, however, it was destroyed by the Romans after the Jewish rebellion. It is likely that John’s Gospel was written with the knowledge of the second temple’s destruction and in response to it.

The theme of Jesus as the temple of God is already indicated at 1:14 where we read that the Word became flesh and (literally) “pitched his tent” among us, revealing the divine glory. The temple, which replaced the tabernacle or tent in the wilderness, was the place where God’s glory dwelt: a saving, life-giving presence. But, for John, Jesus is the dwelling-place, the abiding-place, of God’s glory, giving salvation and life through his death and resurrection.

The two parts of John’s cleansing narrative dovetail together but they are not identical. On the one hand, the temple is “my Father’s house;” on the other hand, it is “the temple of his body.” Jesus in John’s Gospel is the place where God abides and to see his face is to see the face of God.

Note that, on two occasions the disciples “remember.” They remember the psalmist’s zeal for God’s house (2:17; Psalm 69:9). And they remember Jesus’ words following his resurrection (2:22). Remembering is part of John’s spiritually, effected by the Holy Spirit who draws us back, again and again, to the life-giving and dynamic words of the one who is the Word (14:26).

The story ends on a rather skeptical note. Jesus’ reaction to those who seem at first to respond positively to his message is less than enthusiastic. The Johannine Jesus has perceptive divine knowledge into the human heart and is not carried away by his popularity. In John’s Gospel we meet others who believe at first and then withdraw (for example 8:31-38).

There is much material here for preaching. We could pursue the theme of what it might mean for us, in our churches and in our wider society, to purify “my Father’s house.” What is it among us that is in need of cleansing? We could focus on the theme of remembering and what remembrance means in our worship, our spirituality and in our lives. But whatever theme we pursue, at the center stands the One who is the temple of God and who radiates God’s life-giving and loving glory. We are called to enter into his relationship with God, his zeal for God, his worship of God. Only in union with him can we truly worship, in our hearts and in our lives.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Patient God,

Your son, Jesus, expressed anger at abuses and injustice. Help us to show concern, not apathy, for injustice in our world, and teach us to make right all that may be wrong. Amen.

HYMNS

Wash, O God, our sons and daughters ELW 445, UMH 605

In his temple now behold him ELW 417

Built on a rock ELW 652

CHORAL

My song shall be alway, Gerald Near

January 16, 2022