Commentary on Isaiah 2:1-5

To preach on this text stands us in good stead: Isaiah preached on it, too! Or so it seems. The text occurs twice in the Bible-with minor variations-here in Isaiah and again in Micah 4:1-3.

Interpreters have had as little success solving the “Which came first?” question as folks have had with the proverbial chicken and egg. Micah and Isaiah are contemporaries, both prophets of the eighth century B.C.E. and both concerned primarily with issues of justice and integrity before God in a time of social inequality and hypocritical worship.

Yet, despite their common messages of judgment and calls to repentance, both prophets pick up this oracle about the nations coming to Zion where they will beat their swords into plowshares and learn war no more. And, “pick up this oracle” is apparently just what both of them do-take an existing oracle of promise and preach on it for their own purposes.

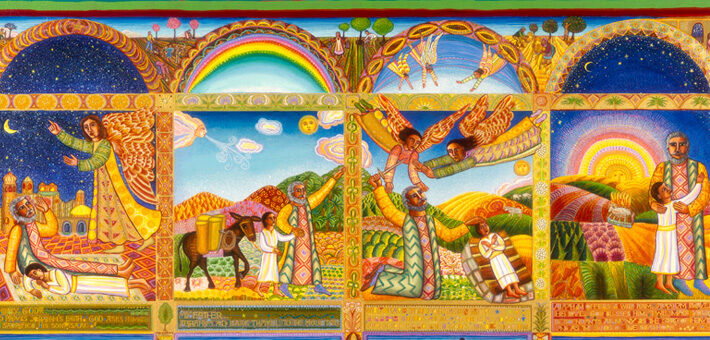

“In days to come,” says Isaiah, signaling that, however attractive the promise of no more war sounds, it is not one that we can usher in in our own time or in our own way. When and how it comes is God’s business-though this does not at all mean that the word has no hook for present hearers. If it is merely an isolated promise of a messianic age somewhere over the rainbow then it may perhaps have no immediate application-then or now. But Isaiah anchors it in his own history (“The word that Isaiah son of Amoz saw…”) and then uses it to make a timely point. We will do well to follow his example. The passage represents one of the traditions of Zion, important throughout the book of Isaiah, in which the nations recognize the presence of God on God’s holy mountain and come streaming in. Unlike some of the Zion psalms (Pss 46; 48), here the nations do not come defeated, but positively and voluntarily in order to learn God’s ways, walk in God’s paths, study Torah (“instruction,” v. 3), and hear the word of the Lord. It is that turn to the ways of God that will motivate the destruction of the implements of war and the rejection of war itself. Amazing! Wonderful! And how do we get there from here?

That is where Isaiah turns this into a sermon for his own people. He, too, knows that the kingdom to come is not theirs to construct, but he has something to say about life in the meantime. He follows the peace oracle with a warning to Israel that is addressed in precisely the same way:

The Nations

Address: “Come let us go up to the mountain of the Lord.” (v. 3)

Promise: “For out of Zion shall go forth instruction.” (v. 3)

Isaiah to Israel

Address: “Come, let us walk in the light of the Lord!” (v. 5)

Promise: “For thou hast rejected thy people, the house of Jacob, because they are full of diviners from the east.” (v. 6 RSV)

Isaiah takes this perhaps familiar promise of peace and transforms it into a sermon in which, surprisingly, the nations become role models for Israel. Returning to his theme of judgment, Isaiah admonishes Israel to come and relearn God’s ways, following the lead of the nations who, coming to seek Torah, have now become the teachers of Israel. Isaiah seeks to shock Israel out of its complacency by demonstrating how the nations have chosen a better way. The nations, more commonly seen as bad influences on Israel (and again, for example, in 2:6-8), make a breakthrough in the peace oracle, opened by God to a radical conversion that God’s word through Isaiah makes possible for Israel as well.

What shall we do with this sermon? Advent, as we know, is a time of hope and longing, but also a time of repentance. Isaiah reminds Israel (and us) that we can’t appreciate the promise without hearing the judgment. If there is no need, there is nothing for which to hope. As preachers, we will have to name the need, the recalcitrance, the resistance to God’s peace, of our congregations (and ourselves) so they can repent and return to the ways and paths of God. Like Israel, we, too, stand under the judgment of God; and-precisely for that reason-for us, too, the promise is overwhelming. God is taking us somewhere we cannot go on our own, not because of our righteousness, but because of God’s goodness. The coming peace is God’s, but it is promised to us. And thus, like Israel, Isaiah calls us to act in the meantime as though the promise is ours. We cannot usher in the kingdom of peace. But, by God’s grace, we can practice peace-within ourselves, among our families, in our congregations, in our neighborhoods, for our world. Why not? “Blessed are the peacemakers!” Christmas comes not to awaken nostalgia, but to awaken our hearts to the ways of God, calling us to conversion and setting us free to be agents of God in the world to which Christ came-even, as Israel is urged to do, to learn from and make common cause with the “nations,” the outsiders, the others. For, under God’s instruction, there is no more “other,” no more “we” and “they”; and until that happens, there is no peace. God is taking us there, says Isaiah, and, though that kingdom is not ours to make, it is ours to practice-for, as we learn at Christmas, it has come in person to reside in our midst. Perhaps by practicing God’s peace we can make our own little piece of “Zion” begin to reflect some of the attractiveness of Isaiah’s “mountain of the Lord” that will draw others to come and see just what God is up to among these odd people who worship a baby in a manger.

December 2, 2007