Commentary on Romans 13:11-14

In this brief but extremely rich passage, Paul tells us that as Christians we are all “morning people.” The time is just before dawn, the sky is brightening, the alarm is ringing, day is at hand. It is time to rouse our minds from slumber, to be alert to what God is doing in the world, and to live in accordance with God’s coming salvation.

This “wake up call” comes in the midst of teaching about mutual love and acceptance in the fellowship of faith (13:8-10; 14:1-15:6); Paul interrupts himself to remind his hearers of their common hope in the clear and revealing light of God’s coming day of salvation (vv. 12-13). This hope is the motivator for the new ways of relating to one another that Paul wants the Jewish and Gentile Roman Christians to adopt.

Amidst the bitter divisions eroding our churches today, both local and global, Paul’s words bring needed perspective. In the wonderfully countercultural season of Advent, he gives us a way to name the present situation: it is still dark, still night. We still indulge in quarreling and jealousy. Paul intends to give us “night vision” to see and name this division as “darkness” (see also the parallel passages in 1 Thessalonians 5:1-11 and Ephesians 6:10-20).

When we wake up, we get dressed. Paul tells us what to wear: “let us put on the armor of light” (v.12); and “put on the Lord Jesus Christ (v. 14). Why the military image of armor? It’s as if we are awakened suddenly from a dream of nighttime revelry, and discover that we are in a military encampment during the hours just before dawn. The camp is astir, preparing for imminent battle; sniffing the wind, scanning the horizon, the soldiers put on their armor and don their weapons.

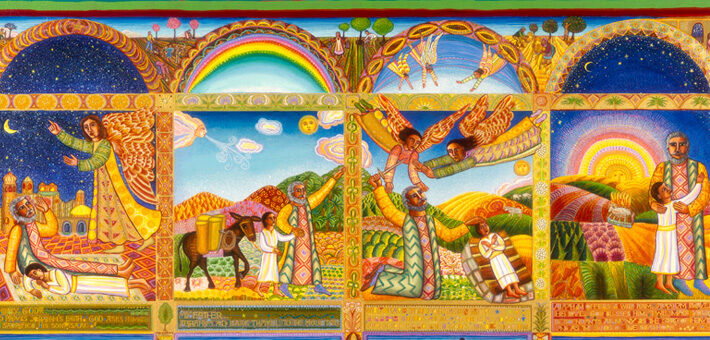

The image tells us that we’re in the middle of conflict; instead of fighting each other, we need to unite against a common enemy. In parallel passages (Ephesians 6:10-20; Romans 8:38-39) Paul names the enemy as “not flesh and blood,” but “principalities, powers, the world rules of this present darkness, the spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places.” How can we make sense of this language in our pulpits today?

First, our enemies are “not flesh and blood.” As Christians, we are never to consider other people as our enemies, no matter how bitter the divisions in the church may be, nor how painful our experiences. Rather, we are to fight against the destructive powers that enslave and divide people. That might be a history of mistrust and injustice, addictions, thirst for revenge, prejudice and fear, greed, and so forth. Paul calls these “the works of darkness,” identified with the “the desires of the flesh” (see Gal 5:19-21 for “the works of the flesh”). It is often the petty manifestations of these powers that erode our fellowship and our witness. When we engage in battle against such destructive powers, we fight for the unity of the church.

Second, the parallel for clothing ourselves in the armor of light is, “put on the Lord Jesus Christ.” Here, the imagery of donning clothing points backwards to the moment of baptism and our hearers’ first profession of faith, recalling Galatians 3:27: “For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ.” This language of “putting on” a person could be used in ancient times to refer to playing the role of a character in a play, “getting into” the role so intensely that we live and breath it day and night, losing and finding our identity in that of the character.

So indeed, for those who have put on Christ, Christ’s destiny becomes our own: “This perishable nature must put on the imperishable, and this mortal nature must put on immortality. When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written: ‘Death is swallowed up in victory'” (1 Corinthians 15:53).

The parallel between putting on the armor of light and putting on the Lord Jesus Christ tells us both that to live out our baptism is inevitably to be in conflict with the status quo, and that Jesus Christ is our sure defense. Paul’s language comes from Isaiah’s description of Israel’s terrible darkness and God’s mighty intervention:

We wait for light, and lo! There is darkness;

And for brightness, but we walk in gloom. . . .

[The Lord] put on righteousness like a breastplate,

and a helmet of salvation on his head;

he put on garments of vengeance for clothing,

and wrapped himself in fury as in a mantle (Isaiah 59:9, 17)

Paul uses the same description of God as Israel’s warrior to describe Jesus Christ, who intervenes on behalf of all humanity. To be baptized into Christ is to be clothed with this mighty power, and to be summoned to battle with all that deflects us from the mutual love enjoined in the larger context of Romans 13:8-15:6, including all that divides the community and sets Christians against one another. At stake is not simply our own health and happiness, but our witness to God’s righteousness in the midst of a hostile world.

In conclusion, this extraordinary text tells us what it means to be “morning people” in the darkness before the dawn:

- We are given “night vision” both to name the ways we and our world are still in darkness, and to see the sure hope of God’s salvation.

- We are summoned to battle, not with other people, but with the forces of destruction that enslave and divide humanity through hatred and fear.

- We “put on” Christ, playing the role given us in baptism and sharing his destiny, just as in the incarnation Christ took on the role of the human race and played it to the end.

- We live out our hope by welcoming and embracing one another as Christ has embraced all of us (Romans 14:1; 15:7).

December 2, 2007