Commentary on Joel 2:23-32

Were anyone to quiz congregants filing in to worship about the content of the little book of Joel, chances are good that few could cogently respond.

Why then, preach from Joel? Several considerations might lead the overly hasty preacher to seek inspiration elsewhere. Joel is, after all, a prophetic book the first half of which deals with an ancient locust plague that lasted for several years (Joel 1:1-4; 2:2-11, 25). This is, at first blush, not a promising preaching selection for contemporary believers, many of whom are likely fuzzy on what a locust looks like.

Add to the book’s unfamiliarity its uncertain provenance: we can say no more than it was written around the year 400 BCE, give or take fifty years.1 Finally, note that the lection hews the biblical text roughly. The exhortation to fast, pray, and repent that occupy the first chapter and a half of the book are finally met with a divine speech of consolation in Joel 2:18-20. For our reading, what can best be described as an assurance of salvation for the land and the children of Zion (verses 21-24) is chopped in two. The LORD’s speech resumes in verses 25 to 27, if not all the way until verse 32 — but only in the English! The Hebrew actually separates verses 28 to 32 into a separate chapter, the first of two that fully describes “the day of the LORD” (see Joel 2:31; 3:14, 18). These are things that will “come to pass” (2:32) “afterward” (2:28), “in those days and in that time” (3:1). In that time, indeed, but not yet. Not even yet today.

Why then, preach from Joel? I propose one ought to consider crafting a sermon from Joel because this prophet proclaims hope to a people then (and now!) who desperately need it.

Two possible approaches to this passage present themselves.

First is the years long plague of locust. One need not imagine the effects of hordes of locusts lasting several years upon people. Joel 1:1-2:11 describe it vividly: literally everything that might provide sustenance is utterly devastated. Food sources disappear; livestock together with the entire nation teeter on the edge of utter annihilation. The people are urged to return to the LORD, to fast, to repent, and to call upon the LORD to spare them (2:12-17). The sin that led to God’s wrath is never specified, but clearly something had gone horribly wrong.

Ancient Israel’s problem was the threat of starvation and the extreme sparsity of those things which make life possible. We dare not minimalize the fact that food insufficiency is a real problem both globally and for fifty million members of the North American population.2 Nevertheless, it is my sense that that most who might appear for worship in late October are anxious about the paucity of resources — material, emotional, spiritual — that have only a little to do with empty larders. What are the resources that enliven us but which are threatened by one metaphorical locust after another? What causes our anxious ceaseless activity? Is it not the fear that whatever little security we have, whatever joys and satisfaction that we cling to might be snatched away in an instant? We consume. We acquire. We support political policies and leaders that promise to perpetuate our lifestyle and that promise to do nothing that will force us to reevaluate the consequences of that lifestyle. Is it not because we have lost faith in a LORD who will provide, and that in spite of what Jesus has to say on the subject (Matthew 6:25-34)?

In response to our worry about scarcity, the LORD our God promises abundance. Joel says that this is the God who gives “rain for your vindication” (li?daqâ). And not just rain! It is “abundant rain the early and later rain” that leads to a superabundance of grain and to vats overflowing with wine and oil.

Joel 2:25-27 make it clear that the promised abundance is still on the way. Eating, praise, and satisfaction are all promises of the wonders to come, as is the twice repeated promise that “my people shall never again be put to shame” (verses 26, 27). The foolishness of faith will be repaid by God’s generous provision and, more importantly, by God’s presence in the midst of God’s people.

In an era like ours and in a culture hallmarked by a fear of scarcity, it is difficult to live lives that are unstinting and free of anxiety about the future. Nevertheless, believers can and do live freely, hopefully, and generously because we know a secret: the God of abundance has promised to care for us at the “hungry feast” until our longings — and those of the world — are fully and forever satisfied.

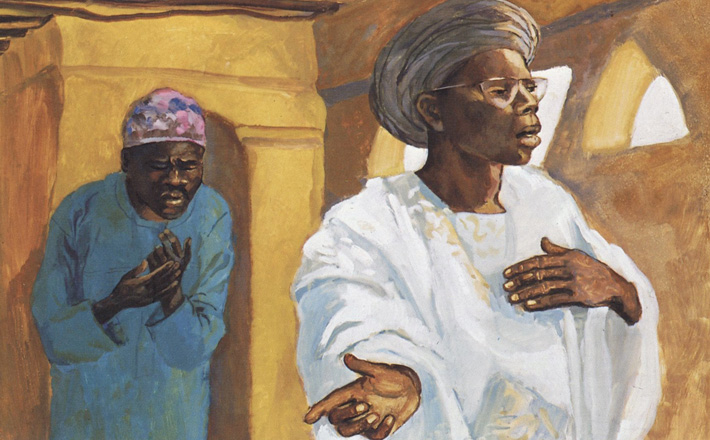

A second preaching possibility presents itself in Joel 2:28-32. The passage is beloved both because it was cited by Peter on the first Pentecost as an interpretation of the work of the Spirit (Acts 2:14-21) and because of the breadth of God’s promise:

- God’s Spirit is poured upon all flesh, unfettered by considerations of gender, age, or social rank. This is good news for all who believe themselves to be unqualified somehow, or too puny to prophesy. The promise is ours. The “Canticle of the Turning” is our

- Portents in the heavens point to the arrival of the “great and terrible day of the LORD.”3 Earlier in Joel, the looming “day of the LORD” caused mourning and alarm (Joel 1:15; 2:1). The locusts were his army and his “day” one of punishment in the form of scarcity (2:11). Now the image is transformed into one of overwhelming abundance (3:13-14, 18).

- “Then everyone who calls on the name of the LORD shall be saved.” God’s loving kindness is available for all in ways we often cannot anticipate.

This last point is at the center of Paul’s claim in Romans 10:11-15. He insists that there is no distinction between Jew and Gentile for “the same Lord is Lord of all and is generous to all who call upon him (Romans 10:12). But how, the Apostle asks, will people hear without someone to proclaim the good news to them? Joel declares that those called upon the LORD are, in turn, called upon by the LORD (Joel 2:32). Regardless of our status, we are “inspired” (in the literal meaning of that word) and summoned by God to be tellers of the good news story of God’s love.

Notes:

1 Daniel J. Simundson, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2005), 122-3.

2 See the ELCA World Hunger web resources at (http://www.elca.org/Our-Work/Relief-and-Development/ELCA-World-Hunger?_ga=1.14601399.1468730017.1458157825). Accessed 3/17/16.

3 “Terrible” is a translation of nôra?, a niphal participle from yare?. The word includes the idea of divine acts are awe-inspiring and wonderful (Deuteronomy 10:21; 2 Samuel 7:23 = 1 Chronicles 17:21, Isaiah 64:2, Psalm 106:22, 145:6).

October 23, 2016