Commentary on Jeremiah 28:5-9

Which way is up? The answer to that question would appear obvious, but not so if one is underwater inside a capsized vessel.

I still recall watching the 1972 movie, “The Poseidon Adventure” as a kid. In particular, I remember the horror I felt watching the scene where the majority of the passengers, rather than head toward the bottom decks of the ship to safety, moved toward the top decks to their doom. Certainly under normal circumstances they would be making the right choice. But since the boat had capsized, what was up was now down, and what was previously down was now up. Getting to safety required rightly assessing the situation and following a reliable guide.

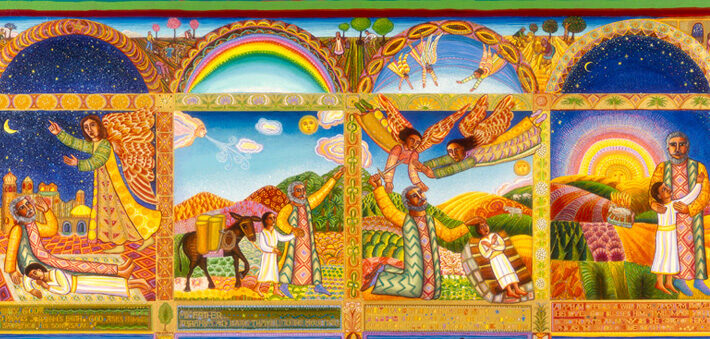

The world of Jeremiah has been turned upside down. Jeremiah himself has been partly responsible for this upside-down-world since his very call as a prophet is “to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow” (Jeremiah 1:10). The world as God’s people knew it was collapsing before their very eyes because they had broken the covenant with their God. It was Jeremiah’s vocation to bring to an end to the covenant Israel made with God at Sinai and codified in the book of Deuteronomy.

Whereas normally the role of a prophet was to pray and intercede on behalf of the people, in Jeremiah 7:16 God instructs Jeremiah to no longer do so. Mt. Zion was considered the mighty fortress of God and impenetrable because of the presence of Yahweh (cf. Psalm 46; 48), yet in Jeremiah 21:1-10 Jeremiah calls upon Zedekiah to surrender Jerusalem over to the Babylonians.

According to the book of Deuteronomy, exile was deemed the curse of the covenant (cf. Deuteronomy 28:49); yet in 24:1-10, God deems exiles as good and those remaining in Jerusalem as worthless and rotten. The Judean king was considered God’s anointed, the Messiah, who was to rule over the nations with an iron rod (cf. Psalm 2); yet in Jeremiah 27:12-13, Jeremiah calls upon King Zedekiah to submit to, and serve the king of Babylon.

In Jeremiah 27 Jeremiah places a yoke on his neck as a sign of the impending yoke of Nebuchadnezzar’s rule upon the region. Jeremiah calls upon King Zedekiah and the people not to resist the rule of the Babylon since it is Yahweh who has given him rule over the nations and creation. Whereas previously the role of the prophets was to call upon Israel’s kings to resist allegiances to foreign kings or powers (e.g., Hosea 5:13; 8:9-11), according to Jeremiah it would now be false prophets would who say such words (27:14-15).

Jeremiah warns the people that it will be the false prophets who will announce a quick end to Babylonian rule (27:16-17). So when Hananiah announces, “Thus says the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel: I have broken the yoke of the king of Babylon. Within two years I will bring back to this place all the vessels of the LORD’s house, which King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon took away from this place and carried to Babylon” (Jeremiah 28:2-3), these words are in direct opposition to the message of Jeremiah. In dramatic fashion, Hananiah goes on to take the yoke from Jeremiah’s neck and breaks it as a sign that the yoke of Nebuchadnezzar’s rule will come to an end within two years (28:10-11).

This prophetic “throwdown” between Jeremiah and Hananiah is a source of much interpretive consternation because the distinction between true and false prophecy is not obvious. The form of Hananiah’s speech and his prophetic actions are no different than that of Jeremiah and are consistent with that of biblical prophets. Hananiah employs the traditional messenger formula, “Thus says the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel,” announces a salvation promise in the form of “I have broken the yoke of the king of Babylon” (28:2), performs a prophetic sign by breaking Jeremiah’s yoke, and concludes his speech with the formula, “says the LORD” in 28:4.

A century ago the prophet Isaiah spoke similar words of encouragement and salvation to King Hezekiah during the Assyrian Crisis of 701 BCE when Sennacherib threatened to conquer Jerusalem. This event is narrated in 2 Kings 18-19 and Isaiah 36-37, and on that occasion the prophet Isaiah disputed the words of Rabshakeh, who urged Hezekiah and the people to surrender the city to the king of Assyria. In this case Isaiah announced that the city would not fall into the hands of the enemy because of Yahweh’s commitment to Zion and the Davidic monarchy (cf. Isaiah 37:35-37).

Some have argued that Hananiah’s timing was simply off; had he lived a century earlier he would be a true prophet. Yet more is going on here than just bad timing. In 28:8 Jeremiah accuses Hananiah of ignoring the prophetic tradition that warned of judgment due to covenant disobedience and announced that exile would not be short-lived (e.g. Hosea 3:4). Jeremiah, possibly in a sarcastic tone, wishes Hananiah’s announcement to come to pass in 28:6.

Yet because he is a truth teller, Jeremiah provides a counterargument in 28:7-8, however unpopular that may have been to his audience. He rests his ultimate trust in the providence of God to affirm true prophecy (28:9; cf. Deuteronomy 18:21-22). Not only does the death of Hananiah demonstrate his prophecy to be false (28:15-17; Deuteronomy 18:19-20), but final form of the book demonstrates Jeremiah’s prophecy to be true. Discernment is required from God’s people to determine the true word of the LORD.

Sometimes God’s prophet speak words that seem utterly contradictory to our sensibilities. In such cases it may not be that the prophet has gotten God’s message confused, but rather God’s people have gotten their priorities reversed. Sometimes it is the vocation of the prophet to say seemingly nonsensical statements such as, “Blessed are the poor, Blessed are those who mourn, Blessed are the persecuted,” in order to proclaim to the world that an upside-down kingdom has come in Jesus.

June 29, 2014