Commentary on Genesis 28:10-19a

Jacob’s surprising encounter with God at Bethel leads to reflection about where we as individuals and as congregations meet God unexpectedly on life’s journey.

In Genesis 28:10-19a, God appears to Jacob en route, as he escapes from his brother Esau’s hatred (Genesis 27:41-45). Jacob, always a “schemer” and “usurper” (meanings of this Hebrew name), has stolen the birthright (Genesis 25:29-34) and the blessing (Genesis 27:1-40) belonging to Esau as Isaac’s firstborn.

Jacob’s grasping for status within the family results also in danger and separation, since to save his life he must leave behind even his beloved mother Rebekah. Jacob’s flight from the southern city of Beer Sheba to the northern city of Haran seems to reverse the celebrated journey of his grandparents Abraham and Sarah, who traveled in faith from their homeland in Haran to the land that God promised their descendants (Genesis 12:1-9).

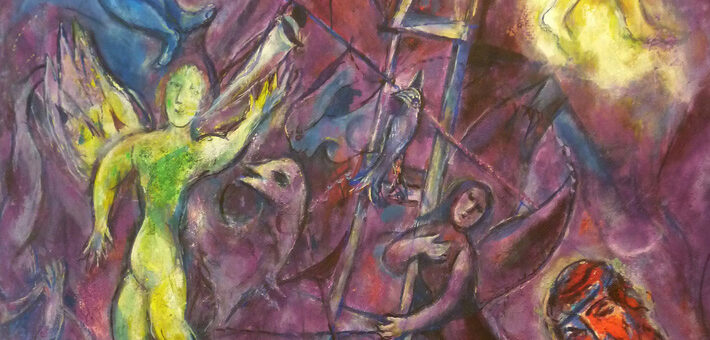

Mid-journey, at a site chosen because of nightfall, Jacob has an extraordinary dream that changes his life. His dream discloses the hidden yet active presence of God at this chance stop along the way. God’s ongoing engagement in the world and in Jacob’s disrupted life is portrayed through a striking vision of stairs reaching from earth to heaven. This structure recalls the stepped ziggurat or mud-brick mountain uniting heaven and earth prominent in Mesopotamian cities such as Babylon, a city whose name means “gate of the gods.” In Genesis God appears not to royalty or priests, but to a terrified refugee.

A Jacob on the move encounters a vision full of movement. Divine errand runners continually ascend and descend to do God’s work in the world. Only the LORD appears stationed at the apex (reading the Hebrew ‘alav in verse 13 as “above it,” as in the KJV and NEB). Jacob is startled to recognize this place of God’s indwelling as holy ground, as “the house of God” (the Hebrew meaning of “Bethel”) and “the gate of heaven” (verse 17). Consecrating his rock pillow as a commemorative pillar, Jacob fittingly names what will become the major Israelite shrine of Bethel. (See also Abraham’s earlier calling on the name of the LORD at an altar east of Bethel in Genesis 12:8.)

Jacob’s dream is not only awe-inspiring and majestic, but also intimate and personal. In an alternative translation, God stands “beside him” (another reading of the Hebrew ‘alav, as in the NRSV) as he lies on the ground, promising to be with him wherever he goes: “Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go” (verse 15). God’s words at Bethel initiate a covenant with Jacob, an enduring relationship committed to his well-being and future.

God’s self-revelation with a personal name, the LORD (YHWH), grounds the covenant relationship with Jacob (verse 13). The very God who in earlier generations established a covenant with Abraham and Isaac now speaks with Jacob about an enduring connection extending to his descendants. Alone and in a strange place, Jacob becomes part of an intergenerational relationship with God. Promises of return to the particular land on which he lies, many descendants, and widespread blessing (verses 13-14) mark the abundance of this relationship.

Ordinary people are the means for God’s widespread blessing. God announces that “all the families of the earth shall be blessed in you and in your offspring” (Genesis 28:14). Earlier Esau protests, “Have you only one blessing, father? Bless me, me also, father!” and weeps in frustration at being excluded (Genesis 27:38). The coveted blessing that destroy this family is countered with God’s alternative vision. Rather than a limited blessing won through defeat and humiliation of others, God extends a prodigal blessing to all the families of the earth through Jacob and his descendants.

Blessing will be as widespread as the “dust,” the loose dirt that covers the ground in every direction and provides the thin layer of fertility sustaining all life on earth. Earlier promises compared descendants to stars or sand (Genesis 15:5; 22:17; 26:4), emphasizing vast numbers. The humble imagery of topsoil adds an insight about the productivity of Jacob’s family as a means for God’s blessing of all families. The ground’s fertility is an especially compelling symbol of blessing in our age of environmental concern.

Jacob’s concluding vow (Genesis 28:20-22) is not part of the First Lesson. This vow may cause discomfort since Jacob appears to be bargaining with God, requiring God to fulfill every promise before Jacob will acknowledge him at Bethel. This interpretation of Jacob’s vow as a calculated set of conditions fits well with his character as a striver, one who prevails in his wrestling with humans and with God, to be given the new name “Israel” (Genesis 32:28).

A more charitable interpretation of Jacob’s vow might view it as an appropriate response, since it is wise to test a subjective experience such as a dream. Questioning, doubt, and discernment are all part of the faith journey.

Another interpretation that attends more precisely to the grammar of the vow places the emphasis on Jacob’s intention to return to Bethel, in recognition of what God has done. Rather than setting conditions, Jacob simply paraphrases God’s promises — to be with him in the journey, to protect and provide for him in every way, to return him home finally (Genesis 28:15, 20-21) — in other words, to act as Jacob’s God.

The final conditional “if” clause of the vow in this interpretation consists of a summary, “if [in doing all these things] the LORD shall be my God,” with the resulting “then” clauses beginning with “then this stone, which I have set up for a pillar, shall be God’s house; and all that you give me I will surely give one-tenth to you” (Genesis 28:22).

Jacob’s vow signals the importance of returning to the place where we encounter God most fully. Although Jacob continues on his journey to Haran, he remains oriented to Bethel, “the house of God,” with plans to return for worship and thanksgiving. Jacob’s descendants throughout the earth also hold this particular place as an orienting center. For Christians, Jacob’s vow resonates with our weekly returning from the journey of our daily lives to the place that we encounter God most fully through worship, word, and sacrament.

July 20, 2014