Commentary on Hebrews 13:1-8, 15-16

This is the last of four consecutive weeks that Hebrews has provided the second reading.

A month ago this Hebrew “mini-series” began with the famous definition of faith found at 11:1: “Faith is the assurance [or substance] of things hoped for, the conviction [or proof] of things not seen.” The great Chapter 11 and its remembrance of the heroes and heroines of such faith provided the text for the first two Sundays. Last week we made it to the heavenly City of God, which was compared to the revelation of God on Mt. Sinai. In today’s text we are reminded of some of the exhortations of the final chapter of Hebrews.

I would urge the preacher to read the entirety of Chapter 13, perhaps backing up to 12:28, which serves as a conclusion of the previous section of Hebrews, while providing a transition to the final chapter. Ideally, one would return to 11:1 and read forward in order to appreciate the grand theological sweep of these final three chapters. But it is important to read at least Chapter 13 since the verses the RCL oddly drops (verses 9-14) contains the theological conclusion of the entire epistle.

In these missing verses, Hebrews makes a typological comparison between the death of Jesus and a sin offering in the cult of the Tabernacle (the “tent of meeting” that provided the holy space of worship during the desert wanderings of the people of God). This analogy comes as no surprise to one who has followed Hebrews to this point. But then comes a critical shift in the text. The place of Jesus’ sacrifice is also seen to hold typological meaning. Jesus’ death did not occur within the holy grounds of Tabernacle or Temple, but on the profane ground of a Roman killing field:

For the bodies of those animals whose blood is brought into the sanctuary by the high priest as a sacrifice for sin are burned outside the camp. Therefore Jesus also suffered outside the city gate in order to sanctify the people by his own blood. Let us then go to him outside the camp and bear the abuse he endured. For here we have no lasting city, but we are looking for the city that is to come. (Hebrews 13:11-14).

Here the “high” cultic imagery of Hebrews at long last finds its “goal” (scopus) or center — the cross of Christ. In doing so, the cultic pattern of worship is shattered to birth something new. The holiness associated with the sacred places of Israel’s religious “cult” is redeemed for the sanctification of a most unholy and profane world by means of Christian service to those in need.

This theological insight of Hebrews is similar to the synoptic tradition that reports the ripping of the curtain that closed off the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem temple at the point of Jesus death (Mark 15:38). Similar too is the Johannine interpretation of the oral tradition of Jesus that understands the body of the crucified and risen Christ to be the new locus of God’s very kavod, God’s own glory (John 2:21). The profane becomes holy and the holy profane.

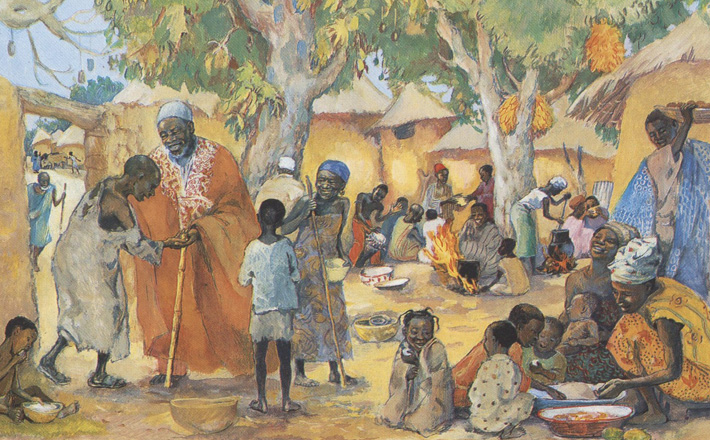

The closing exhortations in Chapter 13, including the demand to practice radical hospitality to strangers, prison visitation, observation of proper boundaries in matters of sexuality, and the proper stewardship of material resources all flow out of this sense that Christ — God in God’s own self — is to be encountered in cruciform mission to a wounded and sorrowful creation, made holy by God’s own reclamation of everything “outside the camp.”

So, what is proper worship of God now that the sacrifice to end all sacrifices has occurred in Christ (10:12)? Hebrews tells us in the final verses of today’s text (verses 15-16). There are two parts to it. The first aspect of this more commonly thought of as “divine service” — what we do in church as we gather to praise and thank God through Christ for the work of Christ (12:15; cf. 4:14). We do this “in the name of Jesus,” as the text says, because it is Jesus who took upon the Sin of the world in his death on the cross for us.

In this service we can offer only the “sacrifice of praise” for what Christ has already done because the “vertical” dimension of the atoning sacrifice is already complete in Christ. The second aspect of what constitutes divine service — the “horizontal” dimension — is another matter. As the final verse in today’s text puts it, “Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.”

It is no accident that “hospitality” is in the “emphatic” or lead position (13:1) in the list of the marks of Christian identity incarnate in service. The other Christian virtues mentioned flow out of this one practice. At one level it is astounding that this beleaguered, suffering, and vulnerable community — one that had experienced the loss of property (10:32-34) — is asked to open itself up as a patron to strangers. Is, then, the practice of hospitality “the cross” that this community must bear? If hospitality is seen as an obligation or duty of Christian discipleship, one might draw this conclusion. If so, it may be a false conclusion.

The Greek word that is traditionally translated in English by “hospitality” is philoxenia, literally, “love of the strange.” Many ancients were locked into lives of routine and did not stray far from their places of birth. Life was difficult and mobility was limited. One way in which the world became “larger” was to open one’s home (however poor) to those that came from “outside.” Hospitality was provided, then, by those who had “love of the strange,” by those who were curious about the wider world.

The unknown seekers of hospitality brought news (and stories!) of the wider world and broke open one’s little provincial world. There was a kind of marvelous exchange, then, of mutual benefit between host and guest. The guest received protection (inns were dangerous places), food, and company. Hosts were led out of themselves and their “little” worlds. Those locked into deadly routine were engaged by that which was “outside” the camp. It is an approach to the outside world with which some contemporary parishes might wish to become better acquainted!

Obviously too, the OT traditions of hospitality are in play here as well. The reference in verse 2 of entertaining “angels without knowing it” is thought to refer to Abraham and Sarah’s reception of the three visitors in Genesis 18:1-15 at the oaks of Mamre. But, of course, the people of God themselves not only practiced hospitality but were long “sojourners” (guests) in foreign lands (11:8-10). The experience of being an alien or sojourner, vulnerable before others and dependent on God as host, was fundamental to Israel’s identity.

Rather than an obligation, “love of the strange” seen from either the Greco-Roman or the OT perspective provides the opportunity to be blessed by exposure to the wider world that God cares deeply about. But that is not all. In the church’s “love of the strange” one actually encounters Christ and so are led out of ourselves (13:13; cf. Matthew 25:37-46). Hospitality, then, is a gift that feeds and nourishes us as well as our guests.

From Hebrews’ perspective, the truth is that we are all sojourners in a land that does not belong to us but, ultimately, to God. Since this is so, Hebrews reminds us that those baptized into the death and the resurrection of Christ are to acknowledge with gratitude God’s ongoing favor to us who are only sojourners. Hebrews also points out, however, that those who are marked by the sign of the cross have a tendency to fall in love with “the strange.” Rather, it’s more like God has fallen in love with us.

September 1, 2013