Commentary on Hebrews 1:1-4

Series Overview

Initial impressions of Hebrews might suggest that the writer is detached from any context.

The opening chapter takes people into the heavenly realm of the angels. In what follows the author seems to live in the world of the Old Testament rather than his own. He quotes passage after passage from the Psalms, ponders the relationship of Jesus to Aaron, then takes people on a tour of the tabernacle that is described in Exodus. One might wonder: What’s the point?

That impression changes when you realize that the writer is addressing issues facing his congregation. He gives us glimpses into three moments in the congregation’s life.

First, his readers began their faith journey on a high point. They had a vivid sense of the goodness of the gospel and the power of God’s Spirit working in their lives (2:2-4).

Second, their newfound faith created tension with others, who did not share their beliefs. They found others marginalizing them and acting with hostility. Yet that negative social pressure made Christian community all the more important, and the congregation pulled together (10:32-34).

But third, that sense of community faded. The gospel initially seemed glorious, but congregational life fell far short of the kingdom of God. Now they faced the challenge of indifference. Things are “dull” (5:11) and “sluggish” (6:12). The congregation is declining — not because of a major crisis but out of neglect (10:25).

The challenge is to reinvigorate a congregation that is faltering and discouraged. And the writer does this through writing that rekindles the imagination. As you preach, think visually. Allow the word pictures to inform your message. The congregation began with a vivid sense of the goodness of the Word. If it is to have a future, the Word must rekindle their faith.

Week 1 (Aug. 9, 2015)

Preaching text: Hebrews 1:1-4

The author begins by focusing on God’s methods of communication. God has spoken in many various ways through Israel’s prophets, but things take a radical turn when God communicates through an embodied Word: the Son. The writer’s opening lines encompass the Son’s inheritance of all things and his activity at creation. The writer will not let the readers’ imaginations remain impoverished with a Christ who is too small. The writer uses words like “radiance” to evoke a sense of divine light entering human sight. He speaks of “exact imprint,” using a term that could refer to the image on a coin. The imprint made visible the very being of God, which was otherwise invisible.

Then the writer sketches out a journey. He follows Jesus from death to glorious life. He goes from making purification for sins through his suffering and death, and to a place above the angels. For a moment readers are taken out of the ordinariness of their situation, as they follow Christ into the presence of God. As readers then and now are drawn into the presence of God in worship, they too go on a journey. It reorients their perception of the situation in which life is lived.

Week 2 (Aug. 16, 2015)

Preaching text: Hebrews 2:10-18

Here the author continues reshaping the readers’ perspectives through his images. One is of Jesus as pioneer. When contemporary readers hear that word they might envision a figure in a coonskin cap, making a way through the American forests toward an unseen world beyond. Or perhaps they think of a pioneer in space travel or a pioneer in medicine or technology. The idea is that a pioneer goes where others have not yet traveled, for the purpose of opening a way that others might follow. This is the way Hebrews portrays Jesus’ way through death to resurrection. Jesus enters fully into the reality of human suffering, in order to open a way to life.

Next the writer turns to images of family life, portraying Jesus as the readers’ brother. He touches on a theme that is all too real in family life: being ashamed. When growing up, one might experience momentary embarrassment when we are trying to impress others, and would rather not be associated with a particular sibling. But there are also the deeper senses of shame that reflect perceptions of failure in relationship. Here, Jesus is “not ashamed” to call others his brothers and sisters. In positive terms that means being valued by Jesus, who himself felt the shame of crucifixion (cf. 12:2). And to those who feel a sense of shame, being valued is a powerfully transformative moment.

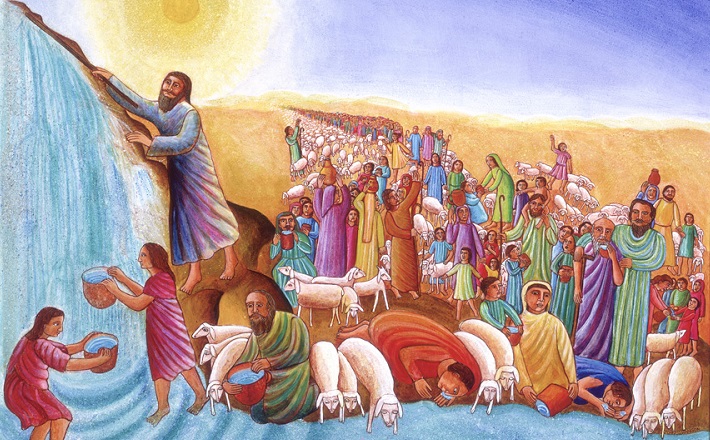

Then Hebrews portrays Jesus as liberator. He uses language reminiscent of the exodus, but transforms it from the deliverance out of slavery in Egypt to liberation from slavery to fear of death. The imagery recognizes that people are held captive by fears that can close off the future. The exodus is replayed on a personal level when fear is overcome so people can more fully embrace life.

Week 3 (Aug. 23, 2015)

Preaching text: Hebrews 4:14-5:10

This passage includes an odd pair of words: sympathy and boldness. The term “sympathy” describes Christ’s role as a priest. The word can seem superficial. When someone says “I’m sympathetic” in casual conversation, it can suggest that the person is more or less inclined to see things your way, but is not ready to go beyond that. In Hebrews, however, sympathy conveys Jesus’ depth of feeling for those who are weak. He enters into the struggle.

The writer recognizes that weakness can include moral failing. And when he describes human priests, he acknowledges that this is all too true. People in ministry are flawed human beings. They understand human sin because they share in it, and being honest about that is important for ministry. It allows people to minister as one flawed human being attending to another.

But the writer explains that when he speaks of Jesus’ sympathizing with weakness, it is about the weakness involved in suffering. He portrays Jesus’ anguished prayer in the face of death. He can sympathize or “feel with” people who suffer, because he has suffered, and that experience empowers his ministry.

The human response to Jesus is boldness” (4:16). What is odd is that we might assume that sympathy encourages passivity. If we are objects of sympathy, we might assume that everyone agrees that things are unfortunate but nothing can change. Yet Jesus’ sympathy is designed to awaken a sense of boldness to approach him in prayer. He enters into suffering in order to empower people to move through the suffering to renewed life in grace.

Week 4 (Aug. 30, 2015)

Preaching text: Hebrews 9:1-14

This is a passage where thinking visually is essential. The writer describes the sanctuary of ancient Israel with its outer court, the curtain that marked its limit, and the place of God’s presence beyond it. Here Jesus is characterized by movement from the outer court to the inner one. The point is to open the way into the presence of God. As you preach, you might move from place to place in your own sanctuary, starting near the door and ending up at the altar. That can help others receive the text with their eyes as well as their ears.

The crux is the notion of a physical barrier that reflects a relational barrier. In human experience a graphic example is an argument in which someone walks out and closes the door. The question is how the relationship can continue when the door is closed. To bring change, a mediator might be needed. One might ask a friend to seek access through the closed door in order to speak with the other person, to open up possibilities for relationship.

That notion of opening the door is vividly depicted here in a surprising way. It is God who wants the door to be opened to us. It is God who sends Christ as the mediator, who conveys the divine love that overcomes the barrier. His death and resurrection open the way to renewed relationship with God. This is about God’s action to restore relationships, which human sins have closed off. The imagery of the sanctuary and liturgical movement in the text demonstrates God’s action in transforming relationships.

Week 5 (Sept. 6, 2015)

Preaching text: Hebrews 11:1-16 [12:1-2]

This section is about the power of the Word of God to evoke faith. The Word is unseen, but its power is visible through its peculiar effects on human beings. The writer assumes that unbelief is the baseline, and his question is why can there be faith at all? (He was writing to a faltering congregation.) The idea is that if there is to be faith, something beyond our senses must pull it into being.

Examples from the past include Noah, who ordinarily would have seen no good reason to build an ark. Why expend the effort if it is not raining? The Word warned of danger and pointed to deliverance, but neither could be seen. And the Word evoked Noah’s willingness to trust and act faithfully for the sake of an unseen future. Abraham and Sarah were called from their home toward a land they could not see. It was the promise of God that moved them to do this.

The readers themselves are being called from despair to hope. The image of the stadium in 12:1-2 portrays it vividly. (Again, think visually.) Readers are like those being drawn into the race by Jesus, who summons them to engagement. Without the Word, there is no reason for this congregation to persevere. Nothing they can see warrants hope. But they continue to be called into Christ’s future, which they may not see but know through the Word of promise.

August 9, 2015