Commentary on Luke 10:25-42

The interpretative subtitles inserted above biblical passages often arrest our hermeneutical gaze.

The subtitles are hermeneutical moves that often make it difficult for readers to see beyond the borders they erect. In the so-called parable of the “Good Samaritan,” no character is described as good or evil. All people are capable of doing good and/or evil. Ultimately, Jesus asks which character in the parable was a neighbor to the man who was robbed and assaulted. Parables as extended metaphors are limited; they steer us in one direction leading us down an interpretative path toward a particular moral conclusion. But we can ask other questions, raise other possibilities, and consider other moral conclusions. That the “Samaritan is good” represents the translator’s/interpreter’s judgment and emphasis.

The parable about a Samaritan man that Jesus identifies as being a neighbor to a man whom bandits victimized is part of Jesus’s response to a lawyer’s inquiry about securing eternal life for himself: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” (verse 25). Jesus, known to the lawyer as a “Teacher,” responds by deferring to the lawyer’s expertise, his pre-knowledge. Like a good counselor or a wise teacher, Jesus encourages the lawyer to answer his own question. According to the Torah, he must love God and love his neighbor as he loves himself (verses 26-27). Jesus affirms the answer, but the lawyer asks a more specific question: “So who is my neighbor?” (verse 29). Whom should he love beyond God and himself? How can he discern who is and is not his neighbor? Phrases and words in laws and sacred texts, like Scripture and the U.S. Constitution, require interpretation. This is a question Jesus is eager to expound upon.

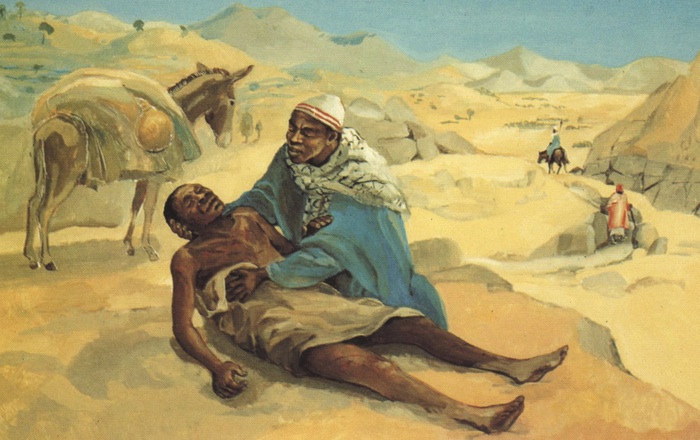

Jesus responds with a parable narrative about human beings and how they respond to traumatized, violated, unsheltered, and/or marginalized others. This parable is about men—a priest, Levite, and Samaritan—who must make significant decisions at the intersection of ethnicity/race, gender, human victimization, and desperation. This is the first mention of a Samaritan since Jesus began his journey to Jerusalem (9:51).

Journeying toward Jerusalem, Jesus healed ten lepers who kept their distance but called out for mercy (17:11-19). Jesus instructed them to present themselves to the priests to confirm that they are clean. Nine of the lepers must have been Jewish or Judeans, since the one who returned to thank Jesus is a Samaritan and a foreigner. Jesus, a Jewish man, held no hostility toward him as a Samaritan (despite a history of collective hostility between the two groups), at least none that prevented Jesus from making the Samaritan whole. The foreigner is a neighbor and neighborly in our parable and in the story of the ten lepers.

The parable begins with a man who is robbed, assaulted, and left for dead when traveling on a road from Jerusalem down to Jericho. We do not know the man’s social class, ethnicity, or religion. He could have been a God Fearer like the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26-40) or the author we call Luke, a Samaritan like the man who stops to help him, or a Jew like the men who pass him by. We know nothing about the moral character of the victimized man. That he is robbed of his clothing indicates his clothes were of value to the robbers, of how much value we do not know. We don’t know if the victimized man had any possessions beyond the clothes on his back; thus, to have them taken would be a great loss.

We seldom humanize robbers and thieves; we do not care why they steal or whether oppressive structures and systems leave people desperate. Desperate people sometimes perform desperate and violent acts—yet not all of them do, and not all the time. Under California’s three strike law, Gregory Taylor was imprisoned for 25 years to life for breaking into a church kitchen because he was hungry.1 Under the Roman Empire, a majority of its subjects were impoverished; wealth was concentrated among 1-3 percent of the population, similar to in the U.S. today. Most nations that permit mass poverty also have cordoned neighborhoods plagued with mass violence.

Persons we think we should treat neighborly are not people we presume to be a threat to our existence and privileges. They are not people who commit crimes, but who are the victims of crimes. Or are they? We are a society more committed to incarceration than rehabilitation, to victim-blaming than to humanizing all. As Bryan Stevenson posits in Just Mercy, none of us are the worst thing we have ever done. Both the priest and Levite saw the injured man and avoided helping him; they moved to the other side of the road, perhaps for fear they too would be victimized. The longer the victim’s wounding is ignored, the less likely it is he will survive.

Unlike the priest and Levite, a Samaritan man approaches the man to see him and his wounds (verse 24). Seeing him and his wounding, he responds like a neighbor who loves himself and loves other human beings. He treats him like he would like to be treated. Not everyone desires to see desperation and suffering up close or can imagine themselves in the same predicament. Disinterested, dehumanizing distance and ignorance makes no demands and takes no risks for others. In Luke, the Kin*dom of God has drawn near (verse 9); people who love God will draw near to the marginalized, oppressed, victimized, criminalized, incarcerated, and “sinners and tax collectors” (see Luke 5:8, 27-32; 7:36-50; 18:9-14). When do our class, race, gender, ethnic, ideological, cultural, and religious differences promote dehumanization of ourselves and of others? Dehumanizing others dehumanizes us.

Sometimes we are the Samaritan; other times, the priest and Levite. We must more consistently practice neighbor-love motivated by God-love and self-love. Self-love is neither egocentric nor individualistic. Self-love is not obsessed with self-preservation; it takes risks for violated, vulnerable humans living in the borderless neighborhood we inhabit. Housing discrimination, redlining, gated communities, homelessness, poverty, and other inequities allow the privileged and wealthy to choose and limit their neighbors. In our religious imagination, we tend to sanitize the trauma and violence, and avoid any personal or collective risk by changing the view. But the scene of being passed by is replayed in the minds of oppressed and dying children, women, and men.

Jesus’ response to the lawyer’s question redirects his concern from eternal life to this life. Our concern should be saving lives in our lifetimes. What we do now impacts where we find ourselves in the afterlife. The story of Lazarus and the rich man makes this point (Luke 16:19-31). When the Samaritan carried, clothed, housed, fed, and financially supported his neighbor, he turned abstract self-righteous piety into neighbor-love. Neighbor-love is clothed in tangible acts of reparation and restitution (whether we are innocent fellow travelers or perpetrators). The most vulnerable among us live in precarious situations and are subjected to and surrounded by violence.

Luke’s God lifts up and liberates the marginalized and anoints gospel abolitionists to do likewise (see Luke 1:48, 57; 4:18-19). Neighbor-love is transgressive of the borders we erect to avoid risky relationships with others or to create sanitized neighborhoods populated with folks like us.

Notes

- Los Angeles Times, “Three Strikes Law: A Big Error,” https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-aug-19-la-ed-taylor-20100819-story.html

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Compassionate God,

How easily you love those who look unlovable to us! How readily you welcome undesirables into your home! How slow we are to follow your example. Turn our hearts toward all who are considered outcast, shunned, and unclean so that we may love our neighbor without pity or apathy, for the sake of the one who became flesh to cleanse the world of sin and death forever, Jesus Christ our redeemer. Amen.

HYMNS

Jesus calls us; o’er the tumult ELW 696, H82 549, 550, UMH 398, NCH 171, 172

O God of mercy, God of light ELW 714

Spirit of God, descend upon my heart ELW 800, UMH 500, NCH 290

CHORAL

Spirit of God, descend upon my heart, Robert Buckley-Farlee

February 21, 2021