Commentary on Mark 12:28-44

Mark 12:28–44 functions as a penultimate climax to Jesus’ public ministry, crystallizing his turbulent interactions with various leadership groups, represented here by the scribes.

At first glance, the scribes may seem like an entirely independent group, vis-à-vis the Pharisees and temple priests. However, when we track references to scribes across the Markan narrative, we find that, as experts in Jewish legal traditions, they function chiefly as supporting characters for the other two groups, even bridging the ideological space between them. Emerging initially alongside Pharisees in Mark’s early Galilee chapters (see 2:6; 7:1, 5), yet also acting alongside priests in Mark’s later Jerusalem chapters (see 8:31; 10:33; 11:18, 27; 14:1, 43, 53; 15:31), the scribes appear more consistently than any other oppositional group in Mark.

From this broad perspective, Mark 12:28–44 is less about Jesus’ public interactions with scribes specifically than it is about Jesus’ public interactions with all opponents within his native Judaism. While Mark does depict each leadership group with a degree of historical realism, his primary goal is to gather them into a cumulative case for how Jesus’ ministry elicits opposition from local power structures. To be clear, though, Mark is not trying to differentiate Jesus’ ministry from the Jewish culture and traditions that inform and animate it. Rather, he is trying to show how the kingdom of God—a thoroughly Jewish idea and movement in Mark’s narrative—challenges human power structures for the healing of all people.

Mark 12:28–44 accomplishes this goal in three primary ways, best explained in reverse order.

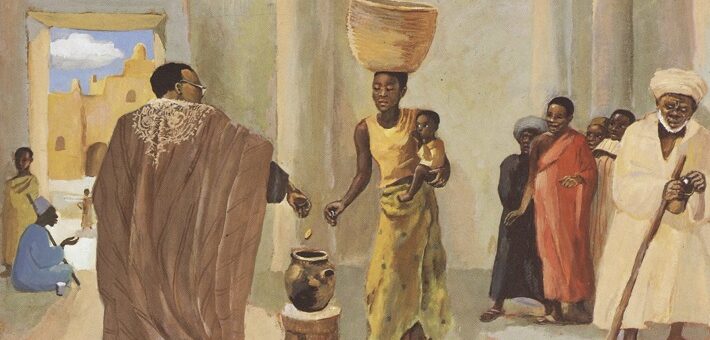

First, Mark shows how Jesus’ consistent focus on the poor and marginalized cuts against the grain of dominant social systems ordered to hierarchies of power and self-aggrandizement. Mark makes this point principally in verses 38–39. Unlike the scribes, who like “to be greeted with respect” and to have “places of honor at banquets,” Jesus dedicates his life to the healing of the broken and marginalized. Jesus does not gravitate to those who hold promise for his own social promotion but to those in need of healing, support, and belonging. He does not exploit the weak to his own advantage—like the scribes, who “devour widows’ houses” (verse 40)—but rather empowers the weak through acts of forgiveness, social inclusion, and physical restoration.

Indeed, within the logic of Mark’s narrative, Jesus goes boldly to the cross precisely because he refuses to back down from this ministry of human healing. He takes on the grotesque and humiliating consequences of his healing mission (trusting, of course, in God’s power to bring life from death) rather than deviate from it, even for a single moment, to save his own life.

Second, Mark 12:28–44 makes the vital point that Jesus’ mission of healing comes directly from the God of Israel. As his conversation with the curious scribe implies, Jesus’ mission manifests the highest commandment to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength” and to “love your neighbor as yourself” (12:30–31).

This is precisely what makes Jesus God’s anointed Messiah—not some mechanical adherence to Old Testament prooftexts but a concrete embodiment of divine love, lived out perfectly and thoroughly, and with the spiritual power to draw others into that same love. When Jesus seeks out the poor and marginalized for restoration, inclusion, and reconciliation, that is precisely the manifestation of God’s love in the world.

Ironically, his is not the standard “Davidic” messianic script endorsed by the scribes (12:35), since it carries no hint of militant, nationalistic fervor. Instead, Jesus creates an alternative community shaped by self-giving and service (8:34–35; 9:35; 10:42–45). While Mark is not exactly opposed to applying Davidic categories to Jesus (10:47–48; 11:10), he makes it clear that the Messiah has now been revealed as David’s lord (12:36–37). As lord, Jesus heals the effects of violence and, ultimately, absorbs violence in order to bring about new life.

Finally, Mark 12:28–34 makes the crucial point that not all scribes stand opposed to Jesus. The significance of this observation cannot be overstated, for it implies that no opposition to Jesus, however entrenched, is entirely closed off to the work of God in the world. This scribe belongs, if only thematically, to the very group that will, along with the temple priests, orchestrate Jesus’ execution. Yet in his recognition of love as the key to devotion and obedience, he is “not far from the kingdom of God” (12:34). That “no one dared to ask [Jesus] any question” after this scene makes Love the last word—and rapprochement the final act—of Jesus’ public ministry in Mark.

I tend to think the Gospels exaggerate the extent to which Pharisees, scribes, and even priests stood opposed to Jesus during his earthly ministry. Of course, some did oppose Jesus—perhaps many did—but likely not in the extreme described by the evangelists. The extreme antagonism toward Jesus in the Gospels better reflects the polemical environment in which the early church forwarded its scandalous claims (“Christ crucified,” as Paul puts it) against manifold detractors. All the more reason, then, to cherish characters like the curious and open scribe, who cautions us against stereotypes—just as Luke’s Joseph of Arimathea cautions us against stereotyping priests (Luke 23:50–51) and John’s Nicodemus cautions us against stereotyping Pharisees (John 3:1–3; 19:39–40).

Adding still more nuance is the fact that, in Mark especially, antagonism toward Jesus is just as likely to come from Jesus’ own disciples. This is the Gospel in which disciples most consistently misunderstand and resist the self-giving heart of Jesus’ healing mission (8:31–33; 9:33–34; 10:35–40), quite apart from the climactic infidelities of Judas and Peter. The overlap between disciple and “enemy” opposition to Jesus is one of Mark’s great pastoral masterstrokes.

Preachers would do well, then, to flip the script on their hearers, presenting the various scribes of Mark 12:28–44 as windows into our own tendencies. We are the ones who choose violence over healing love. We are the ones who pursue self-promotion at the expense of the poor and needy. But we are also the ones whom Jesus will never abandon, whom Jesus always engages in our questions and confusion. At the end of the day, Mark is less concerned with presenting “exceptions” to the rules of characterization than with presenting everyone as equally resistant to Jesus, but also equally loved by him.

PRAYER OF THE DAY

Lord of love, you have taught us that love is your greatest commandment. Teach us to love as unconditionally as you love us. Amen.

HYMNS

Christ is made the sure foundation ELW 645, GG 394, H82 518, NCH 400, UMH 559

Blessing and Honor ELW 854, GG 369

CHORAL

How Great are Thy Wonders, George Schumann

March 10, 2024