Commentary on Psalm 113:1-9

Commentary and hymns for a four-part preaching series on the Psalms.1

This worship and preaching series on the Psalms is meant to move through four psalms in a manner that reflects how believers actually experience the life of faith.

The series loosely follows Walter Brueggemann’s typology that in life we move through a pattern of ups and downs:

- Orientation: When life is stable and the world seems trustworthy (Psalms 113), to

- Disorientation: When the bottom drops out and the tradition feels like a lie (Psalm 69), to

- Reorientation: When faith in a trustworthy God and creation are found again, but the experience of disorientation is not forgotten (Psalms 27 and 40)

Week 1 (June 16, 2019)

Preaching text: Psalm 113; accompanying text: Luke 15:8-10

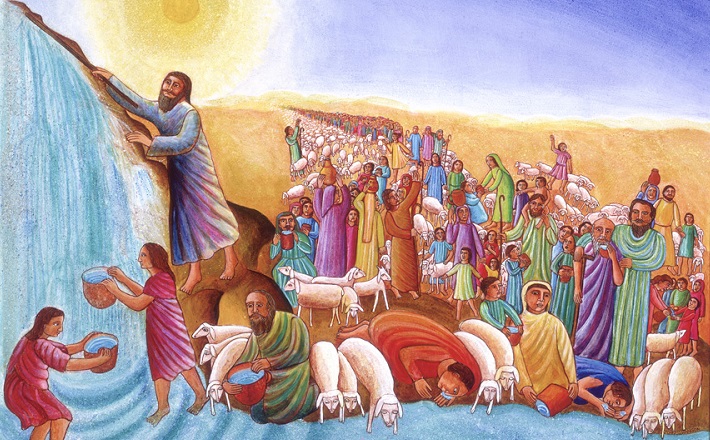

Orientation: God Stoops Down

Psalm 113 is a classic hymn of praise — perhaps we can consider it the class hymn of praise — perfectly embodying the form of a praise psalm: opening call to praise, reasons for praise, closing call to praise. It begins with a triune call to praise, which names the object of praise.

The opening call to praise 1) names whom to praise (the Lord); 2) who is to do the praising (the servants of the Lord); and again, more specifically how to address our praise (to the name of the Lord).

One important aspect here is the connection between praise and being servants of the Lord. Praise is one of the ways that we can become servants of the Lord. In the very act of praising God, we become God’s own people. And the name of the Lord — YHWH — is how we address our praise. This is not generic feeling good or telling an unhearing, impersonal universe that we are grateful for life. No. Our praise is to the personal and communal God of the Bible.

As Reinhard Feldmeier and Hermann Spieckermann write in their seminal God of the Living: A Biblical Theology, God’s name itself “constitutes the ground and object of all petitioning.”2 This is also true of praise. The gift of God’s name both offers us the object of our praise (the Lord) and promises us that our praise shall be heard (because God’s name itself reveals God’s faithful character). Indeed, “The message [of the name of God] can be only that God himself, in his proper name protected by holiness, does not want to keep what is properly his for himself but grant it to those who cannot find life themselves but who, freed in the Exodus for a bond with God, continually receive it anew.”3

By way of offering reasons for praise, the psalm describes God’s self-emptying, gracious intrusion into the life of creation. God is enthroned in heaven (Hebrew root: yashab). But God is not content to be a distant, unmoved creator. Instead God “looks down” on the earth and sees those who suffer — the “poor man” (in Hebrew the noun is singular, not plural) and “the barren woman.” These two — the poor man and the poor, barren woman — typify those whom God loves: both genders — female and male — even in their suffering poverty.

And what does God do? God stoops down and raises them both. To the poor man, God gives a “seat” (Hebrew root: yashab). And to the poor, barren woman God gives a dwelling (Hebrew root: yashab). Thus, in this salvific action, God empties God’s very self of the quality that distinguishes God as holy (God’s sovereign “enthronedness”) and God shares it with the poor, both female and male.

Praise the Lord!

Hymn Suggestions:

- “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty”

- “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing”

- “Praise, My Soul, the God of Heaven”

- “Come, All You People”

Week 2 (June 23, 2019)

Preaching text: Psalm 69:1-16; accompanying text: Matthew 7:7-11

Disorientation: When the Floods Rise

“Save me, O God, for the waters have come up to my neck.”

No image better captured for the ancient Israelites what it feels like when the bottom drops out, than the image of flooding waters. That image is prevalent in the Psalter’s prayers of disorientation (also called “prayers for help” and “laments”), and not just in Psalm 69. For example, Psalm 130 begins with the famous cry, “Out of the depths, I cry to you.” Psalm 42/43 despair, “all your waves and your billows have passed over me” (42:7). And Psalm 88 cries out, “Your dread assaults … enclose me like a flood” (verses 16b-17a).

The image still speaks with surprising force. When have you felt like you were “up to your neck” and couldn’t take any more? When have you felt like you were simply “drowning” in stress or crisis? We still speak this way.

And we still have a God who listens to us in crisis. Who hears us when we pray.

The Psalter’s prayers for help give voice to the deepest expressions of human pain, crisis, and doubt. But they do so in a way that claims the promise of God’s presence in the midst of our suffering and also the promise that the God-who-is-with-us will preserve us.

Psalm 69 speaks of the alienation of the psalmist from “those who hate me” (verse 4), from “my kindred” and “my mother’s children” (verse 8), from the psalmist’s own body (verse 3), and most importantly from God (verse 17). But again, the psalmist nevertheless pleads “do not let the flood sweep over me, or the deep swallow me without cause” (verse 15). And it does so because it believes that the Lord’s very heart is made up of steadfast love and faithfulness: “Answer me, O Lord, for your steadfast love is good” (verse 16).

The psalms of disorientation admit that life is not as well-ordered as a simple Sunday school faith may pretend. They acknowledge that life is really messy, and they protest to heaven that things should not be as they are. But these psalms, through prayer, evoke action from God — they help move the sufferer to a new place. They give us words for the deepest, darkest nights of our lives — when the bottom drops out, when the pain seems too much to bear. They tell us that God is big enough for everything we’ve got — our pain, our anger, our questions, our doubts. They even suggest that genuine biblical faith is comfortable challenging God. And that God is present with us precisely when it feels like God isn’t there.

Hymn Suggestions:

- “What a Friend We Have in Jesus”

- “Create in Me a Clean Heart O God”

- “Kyrie Eleison” (Lord Have Mercy)

- “Lord Teach Us How to Pray Aright”

Week 3 (June 30, 2019)

Preaching text: Psalm 27; accompanying text: Matthew 6:25-34

Disorientation, Part 2 or Reorientation, Part 1: My Light and My Salvation

Very similar to the prayers for help, the psalms of trust are prayed from a situation of severe crisis. What Psalm 27 calls the time when “evildoers assail me” (27:2), or Psalm 46 calls the times when “waters roar and foam” and the “mountains tremble” (46:3). These psalms are very, very clear that life in God’s creation isn’t safe. There are very clear and present dangers.

The major difference between the prayers for help and the psalms of trust is the dominant mood. Both types of psalm depend on God. Both types of psalm at least imply a request for help. And both types of psalm include expressions of trust. But whereas the prayers for help strike the dominant note of fear and desperation, the psalms of trust hit the chord of trust.

For this reason, the psalms of trust have one foot in the “disorientation” camp (because they are spoken in the midst of crisis) and one foot in the “reorientation” camp (because they strike the note of trust rather than terror). The psalms of trust are both “disorientation, part 2” and “reorientation, part 1.”

An interpreter might imagine the prayers for help as the prayers of those who are younger, who are going through their first times of crisis. While the psalms of trust are the words of those who aren’t being thrown from a bull for the first time. This crisis isn’t these psalmists’ first rodeo. They’ve been thrown before, had the floor fall out from beneath them before. And even though the crisis is horrible, they are able to trust on the basis of past experience that a brighter tomorrow will soon dawn.

A personal note: Psalm 27 is a favorite psalm of my own. The first verse alone — “The Lord is my light and my salvation, whom shall I fear?” — has helped me get through many a long night of the soul. When I was a teenager I developed bone cancer, which took both of my legs. As I came through the dark days of cancer, I grew in my trust of God. I never got my legs back, of course. But I learned that God, my light and salvation, is with me always.

When preaching the psalms of trust, be sure to emphasize that these psalms are perfectly clear on how dangerous and deadly life can be. But also that they are words of trust from those who been there before, who’ve had the bottom drop out, but who “cried to the Lord” and were saved.

Hymn Suggestions:

- “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”

- “Through the Night of Doubt and Sorrow”

- “Day by Day (Your Mercies Lord Attend Me)”

Week 4 (July 7, 2019)

Preaching text: Psalm 40:1-10; accompanying text: Luke 17:11-19

Reorientation, Part 2: A New Song

The most famous version of Psalm 40 is by the rock band U2. For many years they ended most concerts singing, “I will sing, sing a new song.”

The “new song” (Hebrew: shir chadash) is most likely a technical Hebrew term for what psalms scholars usually describe as the “song of thanksgiving” — a song that is sung after the psalmist has been delivered by the Lord from the jaws of some crisis.

Brueggemann calls these poems “psalms of reorientation (or new orientation).” These psalms “bear witness to the surprising gift of new life just when none had been expected.”4 They recognize that the ship has sailed through the storm and a new shore has been reached. But having sailed through the flood and the hurricane, there is no going back to a naive harbor childlike “orientation.” These psalms speak for those who have been brought through a deep crisis. As such, they know that faith that speaks the truth can never pretend that all will always be well and that all is as it should be. And yet, they have experienced new life and grace — so they know that despair is not all powerful and evil does not have the last word.

Psalm 40 is typical of the song of thanks because it:

- Describes the time of crisis and how the psalmist asked God for help (verses 1-3)

- Praises God (verses 4-6)

- Describes the help that God gave (verses 7-10)

In regard to Psalm 40, the opening verse is mistranslated in most versions. It should not say, “I waited patiently.” The prayers for help cry out, “How long?!” “I waited and waited” is both a more literal and more faithful translation.

The other thing that should be noted is that the psalm calls for testimony: “I have spoken of your faithfulness and your salvation” (verse 10). When we receive God’s aid, the “thank you note” that God desires is that we tell others where they, too, can find God.

The songs of thanksgiving are reorientation psalms because they are the songs of praise that are sung by those who have walked the darkest valleys, stood in the midst of the shaking mountains, experienced life when the bottom drops out.

Life will never be the same. But God met these sufferers in the depths of their sufferings. And they have a simple message: God found me. Praise the Lord.

Hymn Suggestions:

- “My God How Wonderful Thou Art”

- “Crown Him with Many Crowns”

- “How Great Thou Art”

- “I’m So Glad Jesus Lifted Me”

Notes:

1. Part I of this series was published on this site in June 2012; this part was first published in June 2015.

2. Trans. Mark E. Biddle (Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2011), 17.

4. Walter Brueggemann, Message of the Psalms, (Minneapolis, Minn.: Augsburg Publishing House, 1984), 123-124.

June 16, 2019