Lectionary Commentaries for March 29, 2026

Sunday of the Passion (Palm Sunday)

from WorkingPreacher.org

Gospel

Commentary on Matthew 26:14—27:66

Catherine Sider Hamilton

Alternate Gospel

Commentary on Matthew 21:1-11

Catherine Sider Hamilton

Jesus’s triumphal entry in Matthew’s gospel is intriguing because it is difficult.

Why are there two donkeys? Why does Jesus enter Jerusalem seated on a donkey and a colt? It is impossible, even ridiculous; it makes no sense.

And yet this is exactly what Matthew says: “[The disciples] brought the donkey and the colt and put their cloaks on them and he sat on them” (21:7). He sat on them.

Nor does Matthew say it just once. He says it twice more; he insists on the two donkeys. Jesus tells his disciples they will find “a donkey (onos) tied up and a colt (pōlos) with her” (21:2); he tells them to say to anyone who asks, “The Lord needs them” (21:3). He is going to sit on them both.

Matthew is the only gospel to mention two donkeys. Mark (whom Matthew is following in this narrative) has the colt (pōlos), as does Luke; John has a young donkey (onarion); in all the other gospels, there is just one animal.

What is Matthew doing? Is this just excessive literalism, Matthew reading the parallelism of Zechariah 9:9 (“humble and seated upon a donkey and upon a colt the foal of a donkey,” quoted in Matthew 21:5) to require two donkeys?

As often in Matthew, the Old Testament is illuminating. A closer look at Zechariah helps us see what Matthew is doing.

Zechariah 9:9 announces the coming of the king: “Say to daughter Zion, behold your king comes to you, humble …” This is the time of fulfillment, Matthew tells the reader. The prophets spoke about this day. Jesus riding into Jerusalem on the donkey and the colt is the king God’s people have been waiting for!

Is Matthew just proof-texting, then? Does he (as some scholars have suggested) not understand Hebrew parallelism, thus making two animals out of one?

This seems unlikely, given Matthew’s sophisticated and often profound use of the Scriptures throughout his gospel. He likely does understand poetic parallelism—and still he wants two animals.

Why?

Matthew adds a word to Zechariah. Zechariah has the donkey (hypozygion, in the Greek of the Septuagint) and the colt (pōlos). But where is the onos?

The onos appears not in Zechariah but in Genesis 49:10–11, in the blessing Jacob gives to Judah. “The scepter [Septuagint: ruler] shall not depart from Judah,” Jacob says (49:10). “Tying his foal (pōlos) to the vine and the colt (pōlos) of his donkey (onos) to the choice vine, he washes his garments in wine …” (49:11).

Genesis 49:9–11 became a key passage in Jewish messianic expectation. In adding the word onos to Zechariah’s prophecy, in repeating it, in including both the onos and the polos, Matthew draws Genesis 49:9–11, and with it Jewish messianic hope, into this moment of Jesus’s triumphal entry.

“Your king comes to you,” just as Zechariah has said. And this king who comes on both the colt and the donkey of the blessing given long ago to Judah now enacts the promise to Judah as he enters Jerusalem. “The ruler shall not depart from Judah … until tribute comes to him and the obedience of the peoples is his” (Genesis 49:10): That ruler is here, now, Matthew is saying, in Jesus.

Matthew makes the point again as Jesus rides into Jerusalem. The people shout, “Hosanna to the Son of David!” Only in Matthew do they hail Jesus as Son of David. They are calling him king—the Davidic king, king in the line of Judah (see also Matthew 1:2–6).

Thus those two donkeys are important. With them, by adding the onos—however awkward the image, and precisely because the image is awkward—Matthew identifies Jesus as Son of David, fulfiller of the promise to Judah, the ruler whose reign shall not end until he draws all the peoples to himself (Genesis 49:10d).

And it is Jesus who tells his disciples to find the two donkeys. Jesus declares himself to be the long-awaited king, in a kind of enacted parable. The two donkeys, so unusual—so unnecessary, even—make the point. This is not just any king, humbly riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. This is the Son of David, inheritor of God’s promise to Judah of a throne, and the one who is bringing the promise to pass. Jesus is Israel’s hope.

Palm Sunday, seen through Matthew’s strange narrative—those two donkeys—gives us Jesus as king, Davidic king, in whom Israel’s ancient hope for God’s reign over all the world is being fulfilled, beginning on this day in Jerusalem.

Matthew offers one more reflection on who Jesus is for this Palm Sunday. In the common lectionary cycle the palms and shouts of praise for Jesus lead directly into the Passion. In my Anglican tradition we celebrate both palms and Passion in the same service: first the procession with hymns and palms, singing Jesus’s praise as we enter the church; and then, at the time of the gospel, the reading of the Passion narrative. Even as our king enters Jerusalem in glory, the cross looms.

Matthew, too, sees the cross looming. For he ends this triumphal entry with an irony: The crowds who have just hailed Jesus as “Son of David”—that is, the long-awaited king—say, “This is the prophet Jesus from Nazareth of Galilee” (21:11). The “prophet” Jesus? Their words come nowhere near a full understanding of who Jesus is and what a hope, what a victory, he brings.

And so the way to Golgotha is paved in the tension between what Matthew (and Jesus himself) is showing us about Jesus in those two donkeys, and what the people, in the end, can see. That final irony, the people’s massively inadequate response to who Jesus is, to what they have just seen as he rides into Jerusalem, is unsettling. It drives us, perhaps, to ask what our response to Jesus really is—we who have just waved our palm branches in his praise: Do we, in fact, name Jesus king of our lives?

First Reading

Commentary on Isaiah 50:4-9a

Gregory L. Cuéllar

This text in Second Isaiah (40–55) brings a human body into view. No gender, no name—only a body identified as an “I” subject. Such vagueness leaves the reader to identify only with the subject’s humanity. Here, meaning stays close to the human flesh—close to what the body both does and feels. Before the preacher pivots to theology, the passage offers sufficient bodily detail—tongue (verse 4), ear (verses 4–5), back (verse 6), cheeks (verse 6), beard, and face (verse 6)—to ground interpretation in the realm of the human. To remain with the text’s humanity does not lead to a superior human ideal but rather to human imperfection, frailty, and need.

A mentored tongue

The first body part to appear is the “I” subject’s tongue (verse 4). In prophetic literature, the production of human speech is attributed to the tongue. In the logic of the text, this is what humans do—they speak using their tongues. With the words they speak, their tongues ultimately give rise to a particular world. For the “I” subject, the world that exists points to speech that wounds.

Apart from the “I” subject’s body, other bodies are also present in the text—the exiles. The world they inhabit is not only the result of collective human labor but also of a tongue, a voice, a word, a discourse—hence an ideology. In essence, their displacement and captivity began as the spoken ideas of empire—ideas that denigrate and devalue others for no other reason than to conquer them.

In contrast, God has given the “I” subject a different tongue, one with teachings, or as rendered in the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition, “a trained tongue.” Such a tongue is generously given to the “I” subject, indicating a mentoring dynamic between God and the recipient. Certain forms of speech do not come naturally to the human tongue and therefore require careful instruction and timely training. As this line reveals, speech that heals is not automatic: “that I may know how to sustain the weary (yaʿēf) with a word.”

The term translated as “the weary” also appears in Isaiah 40:29, where it is paralleled with “the powerless” or, more literally, “bodies without strength.” In the context of Second Isaiah, these are the exiles held captive in a place where the empire “show[s] them no mercy” and “[makes its] yoke exceedingly heavy” (Isaiah 47:6). Ultimately, the words and corresponding actions of empire have made their bodies weary and powerless.

Imperial ideology creates an atmosphere that lands on the bodies of the conquered. Their devaluing wears down their personhood. Perhaps the preacher might ask: Who are the exiles or migrants in our midst made weary by wounding speech—words that dehumanize and denigrate?

Turning the body

To care for their weariness, a new discourse is required. For the “I” subject, it begins with a mentored tongue that, in turn, gives rise to a spoken word capable of sustaining bodies made weary by empire. This mentoring occurs “morning by morning,” awakening the ear of the “I” subject to listen “as those who are taught” (verse 4). A tongue that speaks a healing word is not taught in a single day, but over time—little by little—retraining the tongue to speak words of care rather than wounding words.

Healing speech that lifts those made weary by hateful words is, in many ways, the preacher’s task. How can the words preached from pulpits situated within places that devalue and dehumanize the Other be life-giving—and even empowering? How might communities of faith engage in a form of discourse mentorship in which words of healing and love shape the tongues of all their members?

Speaking life under threat

Tracing a movement from tongue to ear, the text turns the reader’s gaze to the back of the “I” subject. This part of the body suggests a turning motion that accompanies the mentoring of healing speech. A tongue that speaks healing to the hurting, in other words, requires a reorientation of the physical body toward a different speech source. To hear words of healing and then voice them, the body must turn in a new direction (verse 5). Here, that turning is away from the agents of empire—those whose way of being is not healing but harming. Yet such a turn carries bodily consequences: The body that turns away from hurtful speech risks being hurt by those in power who rely on it.

Following the mapping of the human body in the text, each identified part is tied to the production of life-giving speech and its consequences. First, there are the tongue and ear, mentored in such a way that they turn the whole body toward a discourse of healing. This embodied form of learning, however, stands in opposition to those in power producing wounding discourse.

In response, the body that speaks healing becomes the site of retaliatory violence. They target the back—the part signifying a turn to a different source of learning and, hence, speaking. They inflict pain on the cheeks—the part closest to the tongue. They spit at the face—the part closest to the ears. Their reaction is consistent with their adversarial way of being, speaking words of insult—that is, a shaming discourse (verse 6). In the end, the body parts that produce words of healing for the weary become targets for violent censorship.

In today’s world, educational spaces that mentor a discourse of life-giving speech for those wearied by greed and hate are likewise targeted for violent silencing. How will the body of the learner, the one formed by healing discourse, continue to speak when the very act of speaking life invites harm? The text offers this response: “The Lord God helps me; therefore I have not been disgraced” (verse 7).

Psalm

Commentary on Psalm 31:9-16

Nancy Koester

The Psalms enrich preaching during Holy Week and Easter, even if few preachers base an entire sermon on a psalm.1

Jesus prayed the Psalms from the cross, and the Gospels quote the Psalms to tell of Jesus’s passion. Strong liturgical traditions invoke the Psalms during Holy Week and Easter. Most importantly, at a season when Jesus’s humanity is so fully revealed, the Psalms show what it means to be a human being before God. No book of the Bible is more forthright about human experience, and none more militantly declares God’s faithfulness, even when God seems absent. There is every reason for preachers to mine the Psalms in Holy Week and Easter, as preachers have done from the beginning of the Christian story.

If your congregation uses this Sunday as Palm Sunday, celebrating Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, you’ll do well to bypass the lectionary psalm and use Psalm 24 instead. “Lift up your heads, O gates! And be lifted up, O ancient doors! That the King of glory may come in” (24:7). This psalm is fit for a king to enter a city. George Frederick Handel thought so too, for this is the text he set to music in his Messiah to evoke Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem before his passion.

But if your congregation observes this day as the Sunday of the Passion, Psalm 31 does important business.

First, it shows human suffering in the most graphic terms. If an aim of worship on this day is to ponder Jesus’s passion, Psalm 31 goes there. Second, Psalm 31 proclaims God’s faithfulness. By quoting this psalm, Jesus expressed his trust in God, even when God did not deliver him from crucifixion.

In Luke’s version of the passion, Jesus died praying Psalm 31:5: “Father, ‘Into your hand I commit my spirit'” (23:46). But Luke did not quote the next line, “You have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God.” Perhaps the implication is that Jesus committed his spirit into God’s hands, no matter what. Jesus never stopped trusting God, even when he felt abandoned.

It could be that Jesus prayed the whole psalm from the cross, writes biblical scholar James Limburg.2 Of course, there is no way to know for sure. But we may faithfully imagine Psalm 31 in the broader context of Holy Week.

Jesus rode into Jerusalem toward his death, yet the people treated him like a conquering hero. They threw down their garments for him to ride over; they waved palm branches and roared their approval. But as Jesus moved through the crowd, he was not moved by their expectations of him. His one desire was to remain faithful to God’s will.

Later that week, Jesus prayed that God might “remove this cup” of suffering; then he committed himself to accept God’s will. Psalm 31 offers a similar prayer: “Take me out of the net that is hidden for me.” But even so, “into your hand I commit my Spirit” (verse 4, 5).

The image of the hand is important in Psalm 31 (verses 5, 8, 15). According to the New Interpreter’s Bible, “hand” means “grasp” or “power.” The psalmist declares that God’s hand upholds him.3 First comes a prayer: “Into your hand I commit my spirit, for you have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God” (31:5). Then comes a statement: “You … have not delivered me into the hand of the enemy, you have set my feet in a broad place” (31:8). And later, despite great suffering, the psalmist affirms, “My times are in your hand,” and continues to pray for deliverance from “the hand of my enemies and persecutors.”

Jesus knew that even when he was literally in the clutches of his foes, they could never grasp or possess him. They might seize him, but they could not hold him. He knew that he was not “in the hand of the enemy” (31:8) but in the “hand” of God (31:5, 15).

Central to this psalm is the confession of trust in God. Preachers call their hearers to look upon Jesus’s suffering through the eyes of faith. Psalm 31:9–13 can be used to help people picture Jesus on the cross. Here we see “an object of dread,” “horror,” and “scorn.” There is no hope of rescue, for Jesus has “passed out of mind like one who is dead” (31:12). His body is broken like a smashed vessel, his eye wasted from grief. Strength fails, and bones waste away. Around his broken body, betrayal is in the air, so thick you can smell it. Enemies sneer and snicker; neighbors flee in terror. The soundtrack for Jesus’s death is mockery and hissing.

No voice of consolation comes from the bystanders. But if Jesus had prayed this entire psalm, there would be inner consolation: “I trust in you, O Lord; I say, ‘You are my God.’ My times are in my hand” (31:14–15).

Yet the psalm is anything but serene. It is not the prayer of one who gives up and welcomes death, but a plea for deliverance “from the hand of my enemies and persecutors” (verse 15). So, too, Jesus prayed, “Remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want” (Mark 14:36). Psalm 31 can be used to help people imagine Jesus’s struggle: first to continue living, and then, while dying, to keep on trusting God. It was a battle all the way.

The psalmist felt separated from God: “I had said in my alarm, ‘I am driven far from your sight'” (31:22). So, too, Jesus felt abandoned as he cried out “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34, quoting Psalm 22:1). Jesus had no advocate, no voice but the Psalms. It seems fitting, then, that preachers listen to these Psalms for the echo of Jesus’s voice.

That voice will resound at Easter in a different key: Trust in God is vindicated by resurrection from the dead. Psalm 31 points toward this hope. It ends with a word of encouragement: “Be strong, and let your heart take courage, all who wait for the Lord” (31:24). It takes courage to follow Jesus through Holy Week. The spectacle of his passion is not for the faint of heart, for to watch Jesus die is to face our own death too. Only by faith can we say, “I trust in you, O Lord. … ‘You are my God,’ my times are in your hand” (31:14–15).

Notes

- Commentary previously published on this website for April 5, 2009.

- James Limburg, Psalms (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2000), 102.

- New Interpreter’s Bible volume VI (Nashville: Abingdon, 1996), 801.

Second Reading

Commentary on Philippians 2:5-11

Luis Menéndez-Antuña

This passage represents one of the most important and influential christological hymns in the New Testament. For a good reason. Paul describes Christ as a kenotic figure, meaning that Christ derives strength through humility: By emptying himself, he is exalted; by obeying, he becomes Lord; and by becoming a servant, he is glorified. This hymn captures what may be the most significant contribution of Christian doctrine and practice to ideas of power and leadership. It is only through the humiliation of the crucifixion that Christ is glorified in the resurrection. But how does this view of “becoming God” relate to similar ideas in the Roman Empire?

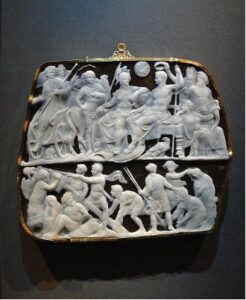

Let us look at a graphic example of Roman views of power, particularly as it pictures a Roman emperor becoming God.

The Gemma Augustea, a significant example of Roman art, is both a visual representation of imperial ideology and an artifact from the Augustan era.1 This cameo is generally dated to around 10 CE and depicts the apotheosis of Augustus, portraying him in divine form alongside personifications of victory and the gods. The Gemma is notable for its intricate depiction of figures that symbolize victory and divine authority, reinforcing Augustus’ status and the restoration of the Roman Republic’s glory following the civil wars.

The cameo features considerable astrological and political symbolism, particularly the Capricorn sign, which was associated with Augustus and illustrated his role as a reborn leader during the winter solstice—a time symbolically linked with renewal. Primarily, the figure of Augustus is at the center of the Gemma. He is shown in a godlike posture, indicating his posthumous deification, a theme prevalent in Augustan propaganda. The procession surrounding him features multiple deities and symbolic representations of virtues valued by the regime.

Among the figures in the cameo is Pax, personifying peace, which emphasizes Augustus’ dedication to establishing the Pax Romana, or Roman Peace, after years of civil conflict. Another important character is Victoria, the goddess of victory, who is shown crowning Augustus with a laurel wreath, symbolizing triumph and divine approval, reinforcing Augustus’ achievements as a military leader and peace-bringer.

Additionally, beside Augustus stands the figure of Rome, personified as a warrior goddess, emphasizing the strength and power of the Roman state under Augustus. This portrayal also signifies Augustus’ deep connection to Roman identity and the empire’s enduring legacy. At his feet, the eagle represents the god Jupiter. Two other historical figures accompany Augustus in the upper register. At the far left is Tiberius, Augustus’ immediate heir to the throne. To the right of Tiberius, standing in front of a chariot, the young Germanicus appears as another member of Augustus’ family entitled to inherit the throne. The message is clear: Augustus’ dynasty is entitled to the highest power.

Other characters include Oikoumene, who represents the civilized world by placing a crown on the emperor’s head. Oceanus, the embodiment of the seas, and Tellus Italiae, the mother earth goddess sitting with two children and a cornucopia symbolizing abundance, complete the scene.

These representations—like many others depicting the emperor wielding his power—serve not just as artistic expressions but also as political propaganda aimed at securing the emperor’s legacy and maintaining the empire’s peace and stability (the Pax Romana mentioned above).

However, notice that the depiction does not shy away from showing the brutal violence involved in the Pax. The lower register is explicit: Roman soldiers raise a trophy while degrading, humiliating, and capturing those who have been defeated. The Roman army would invade different territories, enslaving many of the newly conquered inhabitants and raping many women as they were sold into slavery.

The message is clear: Augustus is a godlike figure because he rules mercilessly over the violently conquered territories.

Katherine Shaner convincingly argues that Philippians 2:6b should be translated “He did not equate being God with rape and robbery.”2 If this is correct, Paul’s christological hymn offers a vivid reversal of imperial ideology, which equates “becoming God” with violence, robbery, and rape. Paul turns upside down, quite literally, the theology behind Gemma’s representation: Whereas the slaves appear in the lower ranks, evincing the emperor’s deification, in Philippians, deification happens through becoming a slave. The contrast could not be starker.

Furthermore, Philippians 2:8 emphasizes the extreme humiliation of the cross. Although the Gemma does not explicitly depict a cross, it’s easy to see how the imperial banner that soldiers plant on the newly conquered land resembles that instrument of torture—especially as humiliated captives stand beneath it and are dragged away, pulled by the hair. This reflects the defiance expressed in this hymn: Instead of placing Christ on the throne, Philippians identifies God with those same captives who will become slaves.

While the imperial depiction shows the oceans, earth, and heaven as part of an oppressive power structure, Philippians notices that “every knee should bow in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (2:10), not because Christ sits dominantly on the throne (like Augustus does), but because he has emptied himself to resemble the captives at the bottom of the hierarchy.

Notes

- The Gemma Augusåtea in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kunsthistorisches_Museum.

- Katherine A. Shaner, “Seeing Rape and Robbery: ἁρπαγμαός and the Philippians Christ Hymn (Phil. 2:5–11)” Biblical Interpretation 25 (2017), 342–363.

Suplementario Evangelio

Comentario del San Mateo 21:1-11

Working Preacher

El comentario sobre este texto será publicado próximamente.

“Then one of the twelve,” Matthew says, “who was called Judas Iscariot, went to the chief priests” (26:14). These are the first words of our gospel, this Passion Sunday. One of the twelve! Jesus’s own disciple betrays him.

Matthew makes a few small changes to Mark (his source text for the Passion narrative) to paint a picture of sin.

In Zechariah, the flock is governed by unscrupulous leaders, and so God sends a shepherd. “Be a shepherd of the flock doomed to slaughter. Those who buy them kill them and go unpunished, and those who sell them say, ‘Blessed be the Lord, for I have become rich,’ and their own shepherds have no pity on them” (Zechariah 11:4–5). The leaders are self-serving; they use their position and even their people for their own advantage, and the people suffer. It was true in the time of Zechariah, it is true in the time of Jesus, and it is true in our time now. So Matthew suggests, in thus folding past and present together in Jesus’s passion.

Judas’s sin is terrible in itself. But in hearing the echo of Zechariah in the blood-money, Matthew says something more. It is not only Judas in his self-interest who betrays Jesus. The leaders are part of this too, and it is the whole people who suffer. Sin is corporate, not just individual, and it affects the whole land (“and they shall devastate the earth,” Zechariah 11:6).

A greedy and self-serving leadership and a devastated earth: Ukraine comes to mind, and food rotting in warehouses in famine-stricken countries, and in rich America, poor families struggling to afford adequate food.

“And their own shepherds have no pity on them” (Zechariah 11:5).

Our gospel hears in Judas’s betrayal of Jesus not only our own individual sins of greed and self-interest but a corrupted leadership and a whole land’s suffering.

Jesus dies for each one of us. And he dies for a devastated world too. “Be a shepherd of the flock doomed to slaughter” (Zechariah 11:4). This is who Matthew sees that Jesus is.

Matthew also makes it clear that Jesus is this shepherd willingly.

When Judas comes to Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane and kisses him—kisses him!—in perfidious greeting, Jesus says to him, “Friend, do what you are here to do.” Then, Matthew says, they arrested Jesus. Jesus is in charge. He accepts the cup the Father is giving him—not lightly, indeed not without that night of agony in the garden—but he chooses this cup. He takes it from Judas, whom he has loved and chosen (“friend”), and he drinks it to the dregs.

Judas betrays him, Peter denies him, and all the rest of his disciples—except for “many women,” who are also Jesus’s followers and who watch from afar (27:55)—run away. The priests and elders condemn and bind him, Pilate washes his hands of him, and the crowds who had just hailed Jesus as their king (“Hosanna to the Son of David!”) shout “Crucify him!” Even the bandits who are crucified with him taunt him.

In the face of human sin, Jesus is the shepherd who is true.

On the night he is betrayed, he acts out for his disciples what his Passion means.

Right after Judas goes to the chief priests and makes his deal, while he is seeking the right moment to betray Jesus, Jesus sits down at supper with his disciples—all of them, including Judas. He blesses the bread and breaks it and gives it to them. “Take, eat, this is my body.” He gives them the cup: “Drink this, all of you, for this is my blood” (26:27–28).

Surely only Judas can have any idea what Jesus is talking about—”my body, … my blood”; but Jesus is giving them, now, the words to understand what is going to happen. My body is going to be broken; my blood is going to be shed; this night it begins. And I give this death to you, Jesus says at the Last Supper, as blessing. “This is my blood of the covenant poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (26:28).

Jesus’s cross is the summation, the end-point, of sin, of all the self-interest and cruelty and corruption of the world, “all the innocent blood poured out upon the earth from Abel … to Zechariah” (Matthew 23:35). All the lands’ devastation is summed up in his dying (“there was darkness over the whole earth,” Matthew 27:45).

Jesus knows the cost of sin, and he takes it on his own back. He lifts it up to the Father on the cross and gives it back to us as forgiveness, God’s own covenant faithfulness.

So his death, which begins in the muck of human corruption, opens out into new life, a world devastated and remade.

In Matthew alone, as Jesus dies, there is an earthquake “and the rocks were split and the tombs were opened and many bodies of the holy ones who had fallen asleep were raised, and they came out of the tombs after his resurrection and came into the holy city and appeared to many” (27:51–53). What a strange scene!

But Matthew is wrapping the cross round with hope. There is real devastation for the land in Jesus’s innocent blood, as in all the innocent blood that has been poured out upon the earth. Darkness covers the land. The earth is shattered.

But this is not the end. By the grace of God there is more to this story than the capacity of human sin to destroy. Jesus’s death, in Matthew, is intertwined with resurrection.

Out of the shattered earth the people rise, bones knit together as God promised in Ezekiel 37, dry bones alive again. They rise at Jesus’s death. And after his resurrection—because the saving act is not complete in Jesus’s death alone, because death and resurrection are two movements in a single song of grace—after his resurrection the risen people of Israel come into the holy city and are seen by many. They are called “saints,” then and now, these people knit together and forgiven, given new life, in Jesus’s blood and his empty tomb.

Matthew takes us, in the Passion narrative, from Judas’s sin to a vision of a people who can be called holy. It happens, the gospel tells us, in Jesus, crucified and risen.