Commentary on John 18:1—19:42

Similar to the gospel lesson for Palm/Passion Sunday, the reading for Good Friday is an extended lesson comprising the whole of Jesus’ passion.

John18-19 takes the reader from Jesus’ arrest, through his trials (first before the Jewish authorities and then before Pilate), to the crucifixion and death, and ends with his burial.

The structure of John’s account is the same as that found in the Synoptics. But the details are quite different — the timing/dating of the events, the role some of the characters play, the use of Hebrew Scripture, the dialogue, and the theology of John’s passion narrative vary significantly from that found in Matthew, Mark and Luke.

Preachers need to consult a critical commentary to explore all of these differences, but in this essay I’ll highlight two that are especially important for preaching this text on Good Friday.

First, is the basic view of the cross itself. This view is presented more in material that precedes the passion narrative than is found in the details of our reading itself. In other words, the narrative leading up to 18-19 significantly shapes the readers’ experience of the story. In the first half of the narrative, Jesus makes clear that his hour to be glorified has not yet arrived (2:4; 7:6, 8 30, 39; 8:20). But just after he enters Jerusalem for the last time, Jesus chooses not to meet some Greeks who are seeking him because his hour to be glorified has arrived (12:23).

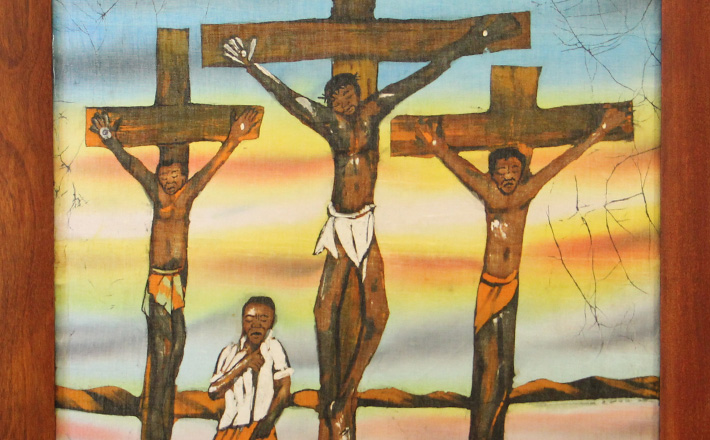

This language signals something important for John. The cross is not to be understood as defeat. The whole of Jesus’ ministry (i.e., the whole of John’s story) leads up to this moment of his being “lifted up” (see 3:14; 8:28; 12:32-33). The cross is the hour of Jesus’ (and God’s) glorification.

Too often the cross is presented as failure which is overcome in the victory of the resurrection. But tradition offers an appropriate understanding of John’s message by calling this day Good Friday. It is the scandalous paradox of the Christian faith that the death of the Son of God is a good thing.

One of the ways John deals with this paradox is to blur the theological lines between death and resurrection. Even though he narrates the death and resurrection in chronological order, throughout the Farewell Discourse, John has Jesus speak of his “departure” in ways that point to the crucifixion as well as the resurrection and ascension (see 13:1, 3, 33, 36; 14:2-5, 18-19, 28; 16:5, 7, 10, 16-19, 28; 17:11, 13). In many ways, for John, the crucifixion through the ascension (including the gift of the Spirit) is a unified salvific event instead of a series of events.

The second unique element of John’s version of the passion supports the first. It is the way the Fourth Gospel presents Jesus as being in charge of his own fate throughout the story:

When the Jewish authorities come to arrest Jesus, he walks out to meet them (18:4).

When Jesus claims that there is no need to question him because he has taught publicly, a guard strikes and rebukes him. But Jesus simply claims that he has spoken rightly and gives no impression of being intimidated (18:19-24).

In his trial before Pilate, not only does Jesus not answer the ruler directly, he assumes the role of investigator by questioning Pilate (18:24). Moreover, when Pilate, exasperated by Jesus’ refusal to answer him, claims to have power over Jesus’ life, Jesus quickly puts Pilate in his place: “You would have no power over me unless it had been given from above” (19:11).

Whereas in the Synoptics, Simon of Cyrene is forced to carry Jesus’ cross (Matthew 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26), John emphatically states that Jesus carries the cross “by himself” (19:17).

And, most striking of all, Jesus seems to be in charge of the moment of his death. He announces, “It is finished,” (19:30). Proof that he was correct in his declaration of completion is seen in the following scene when there is no need to break Jesus’ legs to speed up the process of dying (19:31-34).

This portrayal of Jesus as the one who in some sense choreographs his own suffering and death reinforces the presentation of the crucifixion as an element of God’s plan instead of a defeat which God must overcome with the resurrection.

But just because the death of Jesus is a work of God’s grace does not mean that there is no place for sadness in reflecting on it. The Fourth Gospel describes and interprets the crucifixion with great pathos. Intriguingly, John juxtaposes grief and rejoicing repeatedly in the Farewell Discourse (14:27-28; 15:11; 16:6-7, 16-24; 17:13). While this paradoxical element is not explicitly named in our reading, it is part of the tone of the Passion Narrative, if you will.

And this tone fits perfectly with proclaiming the good news of Jesus’ death on Good Friday in a sanctuary stripped of liturgical colors except for the shroud placed over the cross. Preachers will do well to offer a congregation the unresolved tension of the somberness of watching Jesus die on the cross combined with a celebration of the cross as the moment of Jesus’ glorification. It is not yet the day for leading the assembly in singing “Alleluias!” but we should certainly be able to help them muster up a hearty, “Amen,” even if they do so with a tear in their eyes.

April 6, 2012